The New York Diagnostic Clinic

by Tom Miller

In 1885 real estate developer Charles Batchelor hired Martin V. B. Ferdon to design a row of six upscale homes on the north side of West 72nd Street between Columbus Avenue and Broadway. Faced in brownstone, the high-stooped four-story residences were completed in 1887. August M. Weil, a bachelor, purchased 125 West 72nd Street for his sister Fannie and her husband Maurice Aronstein. It was a generous gift, the price equal to about $1.2 million today.

Maurice Aronstein was born in Germany in 1846 and immigrated to the United States in 1866. He and Fannie had two sons, Albert Sidney and Edgar O. Aronstgein. By the time he moved his family into the West 72nd Street house, he was a senior partner in the lace curtain importing firm of Wolfers & Kalisher. (The junior partner was his brother-in-law, Theodore G. Weil.)

Maurice died in the house on December 23, 1896 and his funeral was held in the parlor two days later. Fannie lived on in the house until her death on September 25, 1917.

When the Aronstein house was constructed, West 72nd Street was known as a “Park Street.” It was maintained by the Parks Department and was highly restricted to both commercial traffic and business. However, by the time of Fannie Aronstein’s death change was coming to that block. Her sons sold the house in August 1918, at which time the Record & Guide pointed out “This is the only block on that street which is not restricted against business.”

Weiss already had a tenant for the remodeled structure, Dr. M. J. Mandelbaum, who headed the Academy of Diagnosis. He worked with Cohen on the plans for what was to be a “diagnostic hospital.”

Benjamin Weiss, president of the Inwood Realty Company, took full advantage of the slackened restrictions. He purchased the Aronstein house and hired architect Samuel Cohen to make “extensive alterations” at the equivalent cost of $5 million in today’s money. Weiss already had a tenant for the remodeled structure, Dr. M. J. Mandelbaum, who headed the Academy of Diagnosis. He worked with Cohen on the plans for what was to be a “diagnostic hospital.”

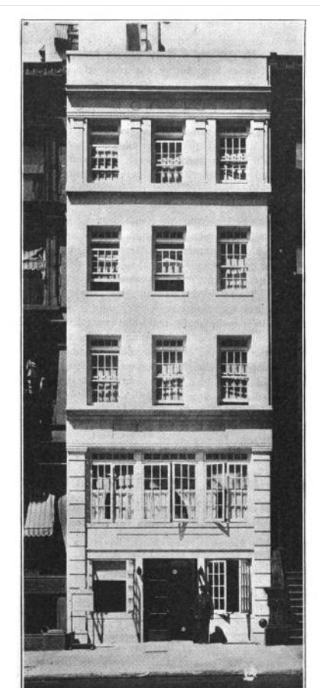

Upon the completion of The New York Diagnostic Clinic in May 1919, there was no remaining trace of the Aronstein residence. Cohen had stripped off the façade and moved the front to the property line. Faced in limestone, its no-nonsense design made no attempt at extravagant ornamentation. Hospital Management magazine noted, “The exterior of the clinic is particularly marked for its seeming height, which is merely an accentuation caused by its extremely narrow frontage of twenty-five feet.”

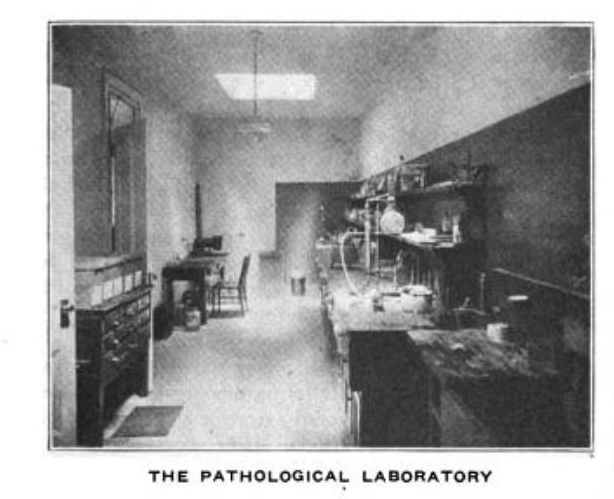

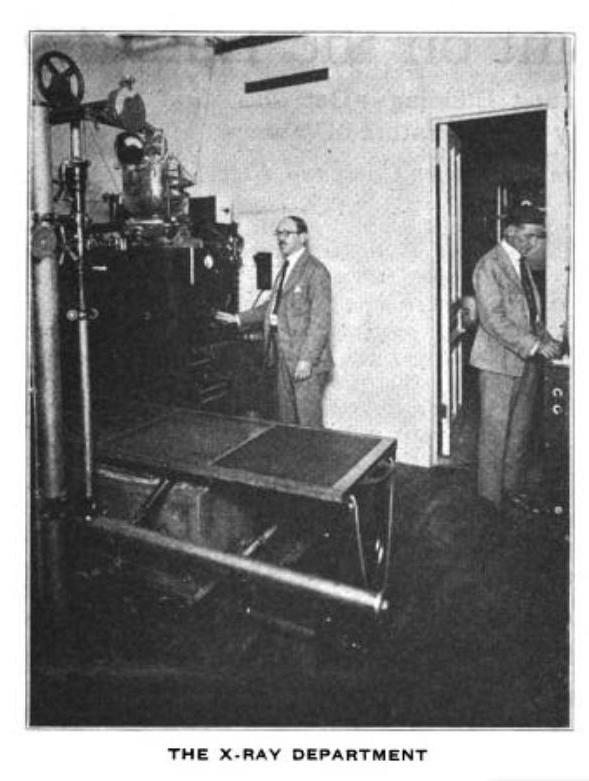

The ground floor entrance opened into a marble trimmed reception hall where an information desk, cashier, and similar offices were housed. In the rear of that floor were the X-ray, pathological, bacteriological, and serological laboratories. The second floor housed “a large well systematized history room, the general medical, and general surgical examining rooms, and waiting and record rooms,” said Hospital Management. The gynecological department filled the third floor and wards were located on the upper floors.

Not every procedure performed in the clinic was purely diagnostic, it seems. On October 19, 1921, the Daily News reported “Dr. Thomas Webster Edgar…who, early this month, transplanted monkey glands into a human being, is demanding that the New York Diagnostic Clinic, 125 West Seventy-second street, give him an ‘inside’ picture of Irving R. Bacon, the subject of the operation.” Edgar had paid the clinic $6 for the X-ray. In court Sadie Underdorfer, a secretary, “explained that in the opinion of the Clinic undue and unethical publicity had been given following the operation.” She said, “If we had known such publicity was to have been given we would not have agreed to make the photograph. The money was refunded when we learned of the publicity.”

The New York Diagnostic Clinic continued to operate in the building until 1930 when renovations designed by architect Samuel A. Hertz resulted in a restaurant on the ground floor and doctors’ offices on the upper floors.

By mid-century non-medical tenants were occupying some of the offices. One caught the attention of the Government—the American Peace Crusade. In a session of the Congressional Committee on Un-American Activities in February 1952, a petition generated by the American Peace Crusade was submitted as evidence of the group’s Communist bent. Harvey M. Matusow presented the petition, saying “it is being distributed in the 48 States of the United States,” adding, “Their whole line is ‘get out of Korea.’”

The Indianapolis Star described the group the following year, on April 23, 1953, saying “This propaganda machine—which is awaiting the return of ex-prisoners of war to launch a POW veterans’ group along left-wing lines—has its national headquarters at 125 West 72d Street, New York City.”

Among the occupants, several were connected to the United Nations, including Venezuelan Ambassador Perez-Perez and his three live-in servants, and Sir Claude Corea of the Ceylon Mission and two associates.

In 1954, the building was renovated again. The restaurant space was converted to retail—home to L. Wein “fine men’s clothing.” There was now a penthouse level with one sprawling apartment. By 1958 the offices spaces in the mid-section had been converted to apartments. Among the occupants, several were connected to the United Nations, including Venezuelan Ambassador Perez-Perez and his three live-in servants, and Sir Claude Corea of the Ceylon Mission and two associates.

In 1986 the store Stationery & Toy—which offered the unexpected mix of office supplies and children’s toys—opened here. A quarter of a century later, on December 23, 2012 it was described by The New York Times journalist David W. Dunlap on December 23, 2012 as “a cherished, packed daughter-and-pop store.”

The store remains there today. The second floor is occupied by an acupuncturist office and there are eleven apartments in the upper floors.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

125 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the business currently at 125 West 72nd Street:

Meet Gary Rowe!

Meet Pam Christenson!