A Victorian Dowager in a Jazz-Age Dress

by Tom Miller

A flurry of construction along the northern side of West 72nd Street between Columbus and Amsterdam Avenues began in 1883. Within two years handsome townhouses intended for affluent families lined the block.

The Irwin-Maturin family lived in the four-story, 18-foot wide Thom & Wilson-designed brick house at 143 West 72nd Street by 1893. Unmarried sisters Jeanne C. and Annie Whitney Irwin-Maturin were members of the Daughters of the American Revolution.

Following their father’s death, their house was offered at auction in March 1895. But when it failed to bring what Irwin-Maturin’s executors felt was a good price, it was withdrawn. (The highest bid was $54,800, or about $1.65 million today.) With the nation still reeling from the Financial Panic of 1893, real estate operators were not surprised at the low bid. The New York Times reported “Many persons were present at the sale of curiosity, apparently expecting to see it go much below its value.” The reporter seems to have thought the executors should have taken the bid. “It would have been a bargain, but not exactly a sacrifice at that price.”

Instead the family took in boarders. One was George Dyre Eldridge, Jr. The young man from Westfield, Massachusetts was attending Columbia College and lived here during the 1896-97 academic year. Twenty-three year old Oswald Simpson boarded here in November 1901 when he was arrested for “driving his vehicle recklessly.”

A succinct advertisement appeared in the New-York Tribune on September 19, 1904, which read simply “72D ST., 143 West – Two large rooms, few stable boarders accommodated, reference.”

When the house was again offered at auction on March 30, 1906, William Broadus Pritchard’s $45,000 bid was successful. Born on June 12, 1862, he had graduated from the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Baltimore in 1884. By now he was well-established and a noted authority on mental disorders. He was the author of various papers published in medical journals. Living with the doctor was his wife, Virginia, and daughter, Elizabeth.

The State hired Dr. Pritchard at $250 a day (more than $7,000 today) to determine Harry Kendall Thaw’s sanity. The “alienist” (the then-popular term for psychiatrist) testified that the defendant “was perfectly rational and knew what he was doing when he shot White.”

Three months after the family moved into the 72nd Street house, Harry Kendall Thaw fatally shot architect Stanford White in Madison Square Garden for dallying with his wife, showgirl Evelyn Nesbit. The State hired Dr. Pritchard at $250 a day (more than $7,000 today) to determine Thaw’s sanity. The “alienist” (the then-popular term for psychiatrist) testified that the defendant “was perfectly rational and knew what he was doing when he shot White.”

Despite his illustrious practice, the case would brand the physician for years. When, for example, trolley conductor John Bell faced charges in the murder of Dr. C. Wilmot Townsend the following year, the New-York Tribune reported “Dr. William B. Pritchard, one of the specialists in the Thaw case, visited the Richmond County Jail yesterday and examined John Bell.”

The relatively quiet block erupted in chaos on the night of September 28, 1910. The New York Times reported “Two groups of men fought a revolver battle in West Seventy-second Street between Columbus Avenue and Broadway yesterday evening about 6 o’clock. The battle ended in a running fight in two motor cars, which continued until the two cars were out of range.”

More than 20 shots were fired, causing pedestrians to duck for cover under the high stoops. One of the cars had been parked directly in front of the Pritchard house when the gunfight broke out. The newspaper reported “One of the bullets pierced the basement window of Dr. Pritchard’s house and badly frightened his butler, who saw the fight.”

Another servant would receive a fright the following year. Sewer workers had erected a small shanty for storing dynamite at the corner of West 72nd Street and Columbus Avenue. On November 23, 1911, a massive explosion occurred that killed one person, injured several others and blew out windows and caused other damage to stores and houses for blocks.

In terms viewed as shockingly racist today, The Times reported, “Dr. William B. Pritchard, the alienist who lives at 143 West Seventy-second Street, lost his cook in the explosion. She is an old negro mammy from the South. She did not stop to investigate, but kept on going when she left the house immediately after the explosion. Dr. Pritchard said she was a good cook, and he hopes she will come back.”

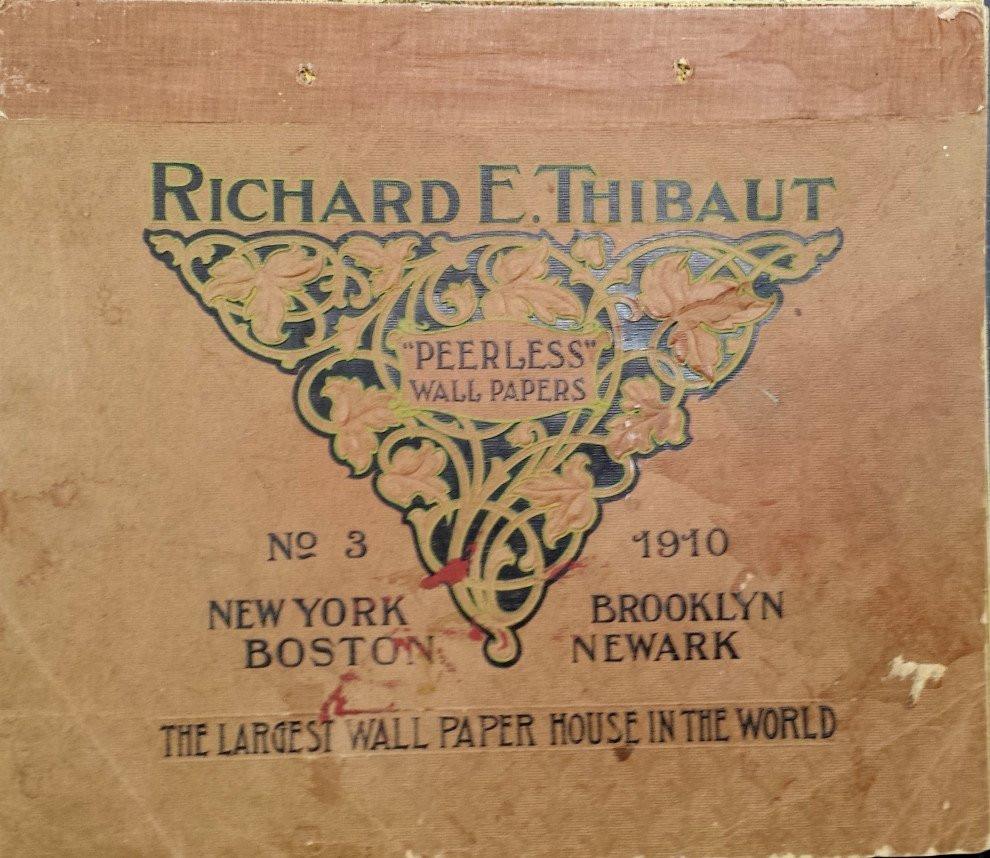

Pritchard was treating millionaire Richard E. Thibaut in 1921 following a nervous breakdown. The patient was at his country estate near Monroe New York on April 13 when he managed to slip away from the attendant Pritchard had put in charge of guarding him. Thibault was discovered dead in the loft of a barn on the property, “hanging by a piece of electric wire from a rafter,” according to The Evening World. Health Officer David H. Sprague listed the cause of death as “accidental strangulation.”

By now West 72nd Street had become heavily commercialized. On April 14, 1922, society columns reported “Mrs. William B. Pritchard and her daughter, Miss Elizabeth Henderson Pritchard, of 143 West Seventy-second Street, are sailing tomorrow on the Baltic and will spend the Summer in England and Switzerland.” The women’s return to West 72nd Street would be just long enough to pack.

On December 2, the Real Estate Record & Builder’s Guide reported that Pritchard had leased his house to the Morton Realty Corporation “for a term of 21 years with two renewal privileges.” The New York Herald added “The two lower floors are to be converted into stores and the upper ones into small suites.”

Architect Samuel A. Hertz removed the stoop and converted the first floor to a restaurant, and the second to an office. The upper floors were “non-housekeeping apartments,” according to Department of Buildings documents, meaning that there could be no cooking done. They were rented as “bachelor apartments.”

Among the tenants in 1927 was 23 year-old James Quinn. He was riding in the Wallace Banks’s car on June 17 in Upper Jay, New York when Banks lost control. The automobile smashed into another car, resulting in a horrific accident. Quinn was removed to a hospital in Plattsburg, but he did not survive.

At the time Arlington Cyrus Hall was extremely well-known in real estate circles. His family had been involved in development for decades, having started out in the 19th century as house builders. His cousins, William W. and Tomas M. Hall were known for their high-end, speculative houses built under the firm name Hall & Hall. Arlington and his brother, Harvey M. Hall, were best known for erecting apartment houses.

Richard E. Thibaut was at his country estate near Monroe New York on April 13 when he managed to slip away from the attendant Pritchard had put in charge of guarding him. Thibault was discovered dead in the loft of a barn on the property, “hanging by a piece of electric wire from a rafter,” according to The Evening World. Health Officer David H. Sprague listed the cause of death as “accidental strangulation.”

In April 1935, Arlington purchased 143 under his own name, paying the $26,600 in cash to the estate of Virginia F. Pritchard. He commissioned the firm of Boak & Paris to remodel the renovated rowhouse into a modern office for A. C. and H. M. Hall Realty Company.

Both Russel M. Boak and Hyman F. Paris had worked in the drafting rooms of architect Emery Roth. They had struck out as partners in 1927 and by now were giving the Art Deco style—most often in the form of apartment buildings –their own architectural personality. And they would lavish the jazzy style on the old Victorian house at 143 West 72nd Street.

The architects removed the top three floors and faced the building in terra cotta. Above the vast, elliptical arched second floor window was the only splash of color—a blind brownish-red roundel that burst vertical and horizontal lines. Incised waves ran below the roof line.

When Arlington C. Hall died on December 2, 1948 in Miami Beach, Florida, A. C. & H. M. Realty Company was still operating from 143. His obituary mentioned that “He specialized in Upper West Side properties.”

In 1965 Swami Prabhupada laid plans to convert the building to a temple. The founder preceptor of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (commonly known as the Hare Krishna Movement) had been shown the property by realtors and, according to biographer Satsvarupa Dasa Goswami, “he had already mentally designed the interior for Deity worship and distribution of prasadam.” Indian Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri was a friend and he scheduled a trip to New York, where it was expected he would authorize a release of funds for the project. But in January 1966 the Prime Minister suffered a fatal heart attack while visiting Russia, putting an abrupt halt to the plans.

Instead, the little building became The House of Games by 1969, described by one newspaper as “the neighborhood center for chess, bridge, backgammon, scrabble and go players.” While there was a retail shop selling board games, the main attraction was the gaming areas that included 50 chess boards. Open 24 hours a day, seven days a week, players paid 60 cents an hour, or $1 a day for students under 16.

When chess champion Bobby Fischer announced a visit to New York City in September 1972, The House of Games responded. A giant banner was stretched across West 72nd Street that read “Congratulations Bobby Fischer, American World Champion 1972.”

In 1989 a project headed by architects The Penta Group was begun which added two floors. Completed the following year, the third floor gave an admirable nod to Boak & Paris’s 1935 design. The blank-walled top floor was less enthusiastic.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

143 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 143 West 72nd Street:

Meet Jen Lobo!

Meet Harmonie Soyk!

Meet Homa Tarzi!