View of 156 West 72nd Street from north. Courtesy NYC Municipal Archive LINK

The Commish and the Prodigal Son-in-Law

by Tom Miller

Developer George J. Hamilton was almost single-handedly responsible for lining the southern side of West 72nd Street between Columbus and Amsterdam Avenues with high-end rowhouses. In 1884, he started a group of five homes that included 156 West 72nd Street. Designed by the firm of Thom & Wilson, they were a creative blend of Northern Renaissance Revival and Queen Anne styles. Four stories tall above a high English basement, the houses were completed in 1886.

A tall stoop led to the parlor floor of 156 West 72nd Street. An angled bay at the second floor was topped by a bulbous copper roof and crowned with a sinuous iron railing. A mansard roof fronted by a triangular pediment filled with a sunburst motif completed the somewhat whimsical design.

The house was sold to Police Commissioner James McClave and his wife, the former Charlotte Louisa Wood. Despite the commodious proportions of the 20-foot-wide residence, it would be a snug fit–the McClaves had 11 children, the youngest being 5 years old.

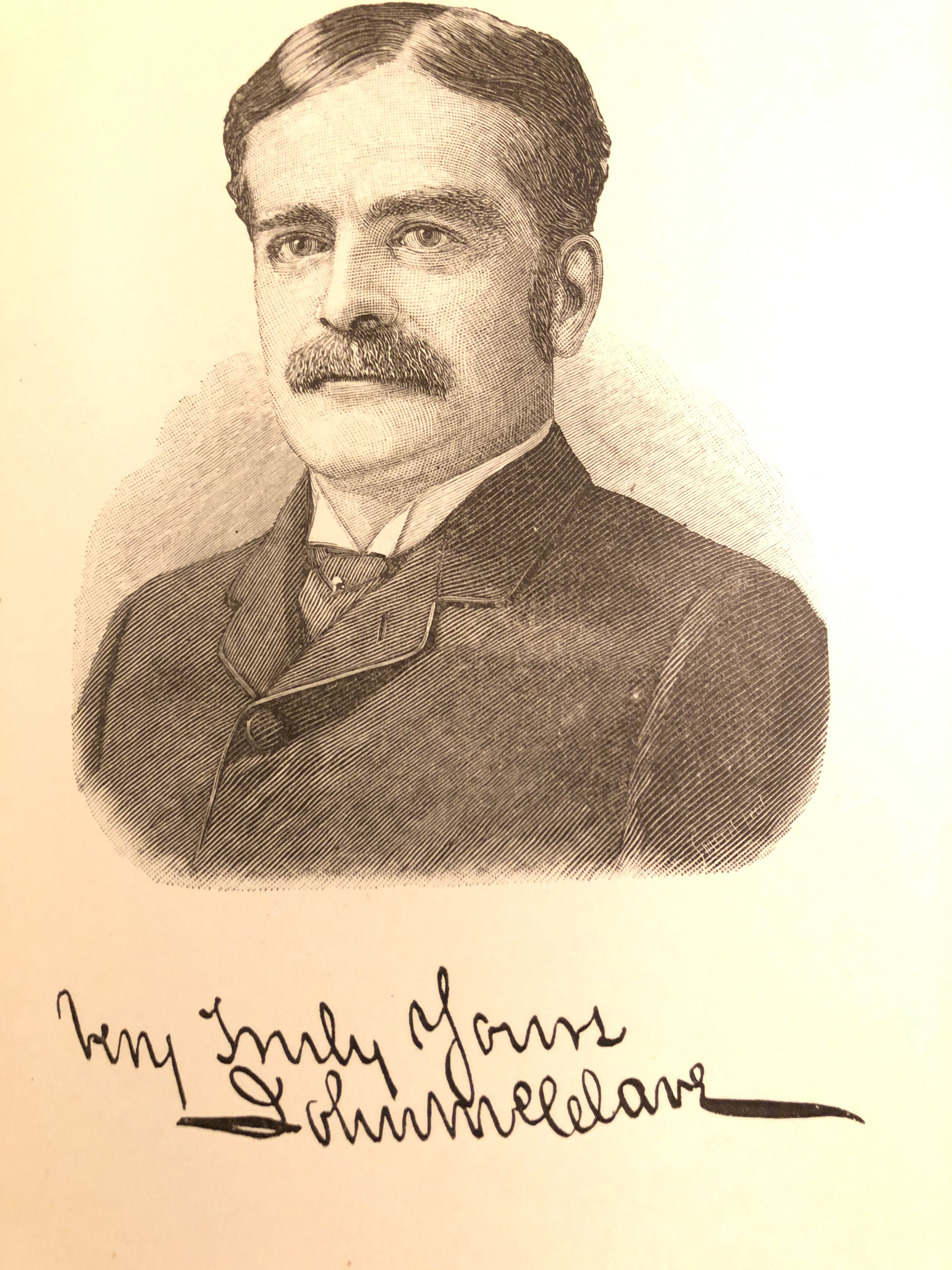

McClave was born in New York on September 11, 1839, the son of a contractor. In 1879, he was elected an Alderman and in 1884 was appointed Police Commissioner. In addition, he was treasurer of the Board of Police and of the Police Pension Fund.

On New Year’s Eve, 1887, Clara Louise was married to Gideon Granger in the Central Baptist Church on 42nd Street near Broadway. The New York Herald noted, “The reception, which will follow at No. 156 West Seventy-second street, will be in honor also of the bride’s parents, who will have been married thirty years on that date.” As it turned out, both Clara and her father would later regret her choice of husbands.

The fact that McClave lived in an expensive home on one of the most exclusive blocks in the city, while making a salary of $5,000 (about $140,000 today), raised doubts.

Three years later, on November 12, 1890, The Press reported, “The first thing Mayor [Hugh J.] Grant did yesterday when he arrived at his office was to reappoint Police Commissioner John McClave.” The article added, “Since Commissioner McClave’s connection with the Police Board as its treasurer, he has handled and disbursed over $31,000,000 without the loss of a single cent.”

That assertation would be called into question before long. The fact that McClave lived in an expensive home on one of the most exclusive blocks in the city, while making a salary of $5,000 (about $140,000 today), raised doubts. The price he had paid for 156 West 72nd Street in 1886 would equal about $1.25 million today.

On June 1, 1894, the Boston Evening Transcript reported that Clara Louise Granger had received an absolute divorce from her husband “on the grounds of infidelity and desertion.” But there was more to the story than that. John McClave was under investigation by the State Senate’s Lexow Committee and Gideon Granger was what The New York Times called “[District Attorney] John W. Goff’s star witness.”

Five days after the divorce, Granger took the stand, “smiling as if he were going to the circus,” according to the New York World. McClave was furious as he listened to his former son-in-law’s detailed description of hefty bribes. When he was called back to testify, McClave denied it all, calling Granger a “scoundrel” and a “forger.” Although never convicted, McClave resigned from the Police Force before year’s end.

Perhaps foreseeing what was coming, McClave sold 156 West 72nd Street two years earlier to William S. Ridabock, who paid him $56,000—more than $1.6 million today. Ridabock lived in the house only five years before selling it to jeweler Benjamin F. Spink on December 20, 1897.

Sprink had two upscale jewelry and silverware shops, one on Sixth Avenue and the other at 9 Maiden Lane. He and his wife summered in the fashionable resort community of Sarasota, New York. They were leasing a cottage there during the summer season of 1903 when they suffered a terrifying accident.

The New-York Tribune reported, “While driving in Ballston-ave., their horse became frightened at an advertising wagon, and ran into a telephone pole. Mr. and Mrs. Spink were thrown violently to the ground, the horse was injured, and the vehicle wrecked.” Mrs. Spink seems to have fared slightly better than her husband. The article said, “Mr. Spink’s ankle was hurt, his face badly bruised and his back wrenched.”

The Spinks leased 156 West 72nd Street to Leroy Coventry “for a term of years with the privilege of purchasing,” according to the New York Times on February 10, 1910. The article noted, “The house will be extensively altered.” The New York Herald added, “The house, which is an old fashioned dwelling, will be altered into store property, and Mr. Coventry will occupy a portion of it as his real estate office.” Already three other houses on the block had been converted for commercial purposes.

Coventry hired architect C. B. Brun to remove the stoop and install a two-story commercial front. The top three floors were renovated to small apartments. An advertisement on August 28, 1910 offered “bachelor apartments, 2 and 3 rooms, bath, valet service.”

Leroy Coventry moved his real estate office into the second-floor space. Among the upstairs tenants were Wladimir W. Yourieff, the Imperial Russian Vice-Consul, and engineer Raymond Gilleaudeau. By 1918 L. Camilieri, who advertised as “conductor and coach, opera, concert, church,” lived and taught in one of the apartments.

“While driving in Ballston-ave., their horse became frightened at an advertising wagon, and ran into a telephone pole. Mr. and Mrs. Spink were thrown violently to the ground, the horse was injured, and the vehicle wrecked.”

In March 1919, the insurance agency of A. V. Amy & Co. took the space formerly held by Leroy Coventry & Co. The following year the ground floor was leased to John Davis, who, according to the Record & Guide, “will run a high class restaurant and rotisserie after alterations are completed.”

The rent for a two-room apartment with bath and kitchenette in 1922 was $1,000 per year—or around $1,250 per month today.

In 1926, John Davis’s restaurant became a Bickford Lunchroom. It would remain in the space until 1950 when Bloom’s Bake Shop moved in. The same year the third and fourth floors were combined into a duplex apartment. There was now just one apartment on the fifth floor.

Bloom’s Bake Shop was in the store space at least through 1970. In the mid-1970’s it was home to Falk, a small appliance store, while the Cartoonists Guild, Inc. occupied the second floor by 1982.

The early 1980’s saw 72nd Street Love, a discount health and beauty store, in the ground floor space. Today the Celina salon, here since around 2000, occupies the second floor, and a children’s clothing shop was recently replaced by Trek Bike Shop which operates from the ground floor. The three upper floors, from the exterior, are little changed since the 13 members of the McCrave family moved in in 1886.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

156 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 156 West 72nd Street:

Meet Lou Jacob!