View of 222 West 72nd Street from north. Courtesy NYC Municipal Archive LINK

Defaced C.P.H. Gilbert Building Turns the Other Cheek

by Tom Miller

In October 1886 architect C. P. H. Gilbert, well-known for designing sumptuous mansions, filed plans for three houses on West 72nd Street between “Grand Boulevard” (formerly, and presently, Broadway) and West End Avenue. Each of the residences would cost developer William H. McCormack $24,000 to build—just over $681,000 each today. Four stories high over tall basements, they were completed in 1887.

Gilbert designed the house in a mixture of Queen Anne and Romanesque Revival styles. The rough-faced brownstone blocks of the stoop, areaway wall, and parlor level quoins were purely Romanesque, as were the arched eyebrows above the parlor windows. But the leaded glass transoms, the pediment over the entrance, and paired gables with their triangular pediments were a nod to the Queen Anne style.

Among them was the 20-foot-wide 222 West 72nd Street. Perhaps because McCormack intended it for his personal use, it was lavishly outfitted. The New York Times noted it had three bathrooms and “decorations by Tiffany.” The newspaper added, “72d St., being 100 ft. wide, under control of the Park Department and restricted to private residences, is the most attractive street on the West Side north of 59th St.”

A bachelor, McCormack moved into the house with his widowed mother, Fannie.

A bachelor, McCormack moved into the house with his widowed mother, Fannie. Shortly afterward, in March 1887, he transferred title to her. In addition, William’s brother, the 22-year-old Lincoln G. McCormack, who was studying law at Columbia University, lived here. Six years later, Lincoln, now married, hired C. P. H. Gilbert to design his own sumptuous home at 311 West 74th Street.

Fannie died in 1889. Eleven years later, in May 1900, her estate sold the house to Edmund Strudwick Nash for the equivalent of $2.25 million today. It may have been William’s failing health that prompted the sale. When he died on July 21, 1901, the New-York Tribune noted, “Bright’s disease was the immediate cause of death, but Mr. McCormack had been for some time an invalid from an attack of typhoid fever.”

The head of the Rosin & Turpentine Export Company, Nash was born in Hillsboro, North Carolina and came from a distinguished American family. His ancestor Abner Nash had been the second Governor of North Carolina and his grandfather, Frederick Nash, had been a Chief Justice of that state. He and his wife, the former Mathilde Cenault, had four children. Shirley Gwendolyn, Edmund Witherell, Ogden, and Aubrey Frederic. (Young Ogden Nash would go on to become one of America’s most beloved poets and humorists.)

The domestic troubles that arose not long after the Nashes bought the house were most likely responsible for its being offered for sale in 1904. Edmund and Mathilde were divorced in 1906. But, instead of selling the house, Edmund leased it that year to a group of doctors. Living and working here were physicians Alexander Nicoll, a surgeon with the Harlem Hospital; Percy H. Williams and his wife; and gynecologist Albert S. Morrow.

Then, in September 1917, Nash leased the mansion to the League for the Larger Life. Listed in The Charity Organization Society in 1919 as a “New Thought” church.” It was the venue for myriad lectures by religious and philosophical leaders.

On October 30, 1920, an article in Scientific American was titled, “Edison’s Views on Life and Death.” Writer Austin C. Lescarboura interviewed the inventor about “his attempt to communicate with the next world.” Three weeks later, on November 24, the New York Herald announced, “Harendranath Maitra will reply to Thomas A. Edison and speak on ‘Life After Death: the Hindu Standpoint,’ at The League for the Larger Life.”

Neighbors knew that she worked from her apartment, but according to one, “never gave much thought to the subject.”

Among the speakers during the first week of November 1922 were Eugene Del Mar, whose subject was “Why Do Things Come?”, and Mrs. Whiting Taylor, who spoke on “The Quintessence of Self.” But the League for the Larger Life would have to find new quarters in 1929. That year the architectural firm of Gronenberg & Leuchtag was hired to renovate the former mansion. The stoop as removed, and a two-story storefront installed. The upper floors were redesigned as “non-housekeeping apartments,” meaning they had no kitchens.

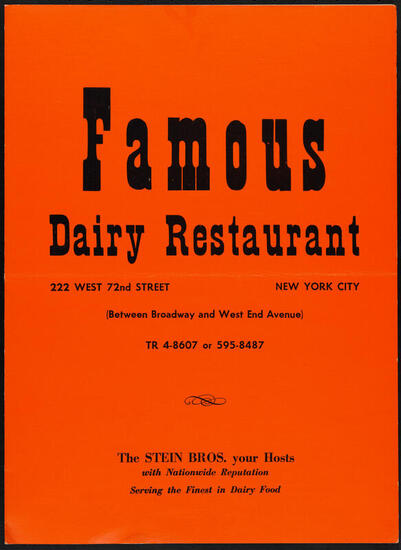

The commercial space became home to the National Association for American Speech. Its head, Dagmar Perkins, also lived in the building. The structure was remodeled again in 1971 for a luncheonette, the Famous Dairy Restaurant. There were now two apartments per floor upstairs. And then, in 1987 a final remodeling was initiated by architect Joseph Feingold, which obliterated any vestige of C. P. H. Gilbert’s once-elegant façade. One cannot imagine that the resultant brick-and-concrete-block façade was considered attractive even in the 1980’s.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

222 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 222 West 72nd Street: