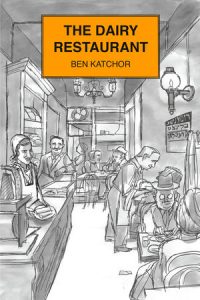

Writer/Cartoonist Ben Katchor

Writer/Cartoonist Ben Katchor produced his thought-provoking and awe-inspiring The Dairy Restaurant, a book of witty illustrations and text in 2020. It’s the only book on Dairy restaurants. Read it. It’s timeless.

As described in The New York Times, it covers the topic of Jews in mid-Century New York, and the history of dairy-style culinary and culture going back to the beginning of history.

How did this idea even occur to him? Katchor says he was familiar with dairy restaurants from childhood and at some point in the 1980s he realized there was no serious book on the subject which he pursued for the next 20 years in the New York Public Library, online, and following up leads he found in newspapers and on tips provided by friend and acquaintances.

Katchor has lived with his wife Susan in an apartment on 102nd Street overlooking Broadway. He grew up in Brooklyn, and graduated from Brooklyn College.

Katchor’s Book, The Dairy Restaurant

He has been teaching for many years at Parsons School of Design and is well known for his imaginative work and widely published cartoon series which, over time have supported the legitimacy of comics as an art form. A man who drew original comics series since childhood, he was part of a select and passionate group of artists who contributed their comics to zines that popularized this form of story-telling long before the Internet. His thoughtful and distinctive work is subtly infused with political and social commentary. It has appeared in a number of books as well as in the English version of The Forward, in the Village Voice, New Yorker, and the New York Times Book Review. He’s now working on an illustrated collection of work entitled Hotel & Farm that alternates stories on fictional hotel culture and agriculture themes. He is the only cartoonist to have received the prestigious MacArthur Foundation Fellowship.

In The Dairy Restaurant, Katchor covers many mostly long-gone restaurants that were once familiar, even legendary through NYC neighborhoods. This was in the days when a restaurant might last 40-50 years acquiring generations of regulars.

Of several established on the Upper West Side, Steinberg’s Dairy Restaurant at 2270 Broadway (early 1930s to 1969) was a favorite among writers and theater people of the Upper West Side. Katchor conjures a time when there were many dairy restaurants each attracting customers, many of whom were working class Jewish immigrants, drawn to have a coffee, a bowl of borscht or a plate of sour cream-topped blintzes with others who shared their place of origin and politics. In addition, Steinberg’s Dairy Restaurant, Katchor notes, provided a kind of comfort and refuge for Upper West Siders of that world whose lives were devastated when they were black-listed during the McCarthy period accused of having Communist sympathies.

Screen shot with Morris Lapidus-designed Steinberg’s Dairy Restaurant as backdrop.

The comedian Zero Mostel was among the list of 19 black-listed actors and directors. He and his family lived in a large apartment they rented at the Belnord just a few blocks north of Steinberg’s. Unlike some others on the black-list, his career recovered after the shameful McCarthy era. Among his many performances, Mostel acted alongside Woody Allen in the 1976 Martin Ritt film, some of which is set at Steinberg’s but was actually filmed at Hammer’s Dairy Restaurant on 14th Street. It was intended according to Mostel to educate about the period.

What was the place like? The food was fresh, tasty, and familiar. Steinberg’s was known to be a bit fancier than some of the other straightforwardly designed restaurants. One of the large menus preserved in the New York Public Library depicts a pastoral farm scene on its cover. Yes, cheese blintzes were on its menu. The New York Times quotes Katchor on Kosher dairy restaurant fare, “The potato knishes, the milkhiker borscht, the cheese kreplekh, the varnishkes, the pirogen, blintzes, buttermilk, and for dessert pudding and poppy cakes — the food of a Jew’s pastoral dream.”

Katchor speculates that the end of the dairy restaurants came as their owners supported their children’s educations, encouraging them to pursue professions in which they would achieve higher status and make more money than their parents. In Katchor’s case, he chose to move in a different direction than his Dad who had pursued chicken farming and real estate, instead he worked hard and long to establish himself as an artist/writer, a job that did not promise riches.

Remnants of Steinberg’s Dairy Restaurant: Katchor makes it clear that items found on eBay like stylized matchbook covers, only hint at the character of the neighborhoods of the past and the cultural influences that defined them. Still, some people treasure finds like photographs and signs that recall history. Katchor noted in The Dairy Restaurant that Lorna Nowvé, a longtime West 72 Street resident who worked for the Municipal Art Society in the 1970s and 80s, (and most recently, at the Historic Districts Council) rescued the Dairy part of the neon sign from a Steinberg’s competitor–the Famous Dairy Restaurant on West 72nd Street–after the restaurant closed. Despite some trouble hauling it away, she placed it as a showpiece in her apartment.

As described in The New York Times, for example, lifelong Upper West Sider Brian Gari “spotted the character Detective Adam Flint and his girlfriend coming out of a luncheonette called Steinberg’s Dairy Restaurant” (during the making of a 1963 episode of the police drama Naked City) whose facade bore the number 2270.”

The Museum of the City of New York holds several photographs of Steinberg’s interior in its collection. A caption on a photograph of Steinberg’s distinctly mid-century modern, geometric-looking interior in a book called The Mythic City: Photographs of New York by Samuel H. Gottscho, 1925-1940,” notes: “Steinberg’s restaurant, 2270 Broadway, 1934. Gottscho’s fascination with luminosity made him the ideal photographer Morris Lapidus, whose commercial interiors of the 1930s abounded in indirectly lit recessed niches and modern light fixtures.”

Architect Morris Lapidus emigrated to NYC as a child from Russia with his family. A graduate of the Columbia School of architecture, his first 20 years of professional life were spent designing interior and exteriors of stores that were executed with distinctively pared-down modernist simplicity in comparison with the over-the-top flamboyance of his later work such as the Fontainebleau and Eden Roc hotels in Miami.