Euclid Hall

by Tom Miller

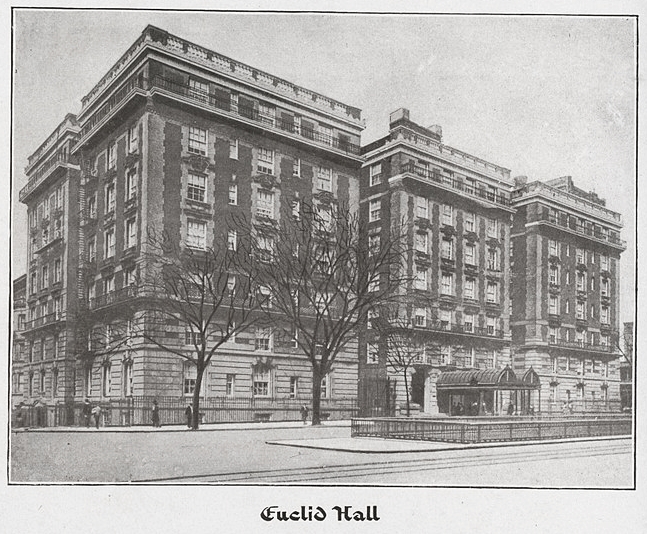

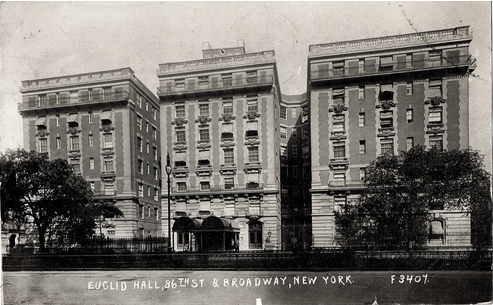

In 1900 wealthy developer Le Grand K. Pettit hired the architectural firm of Hill & Turner to design a sprawling, seven-story apartment building that would engulf the western Broadway block front from 85th to 86th Streets. Their plans, filed in February, estimated the cost of construction at $400,000—a staggering $12.7 million in today’s dollars. The Real Estate Record & Guide commented, “An interesting feature of the plans is that they provide for direct communication between the proposed rapid transit underground station at 86th street and the apartment house by means of private stairways.” The article added, “Tenants of uptown apartments will no doubt appreciate the advantage of being able to step on board trains dry-shod in inclement weather.”

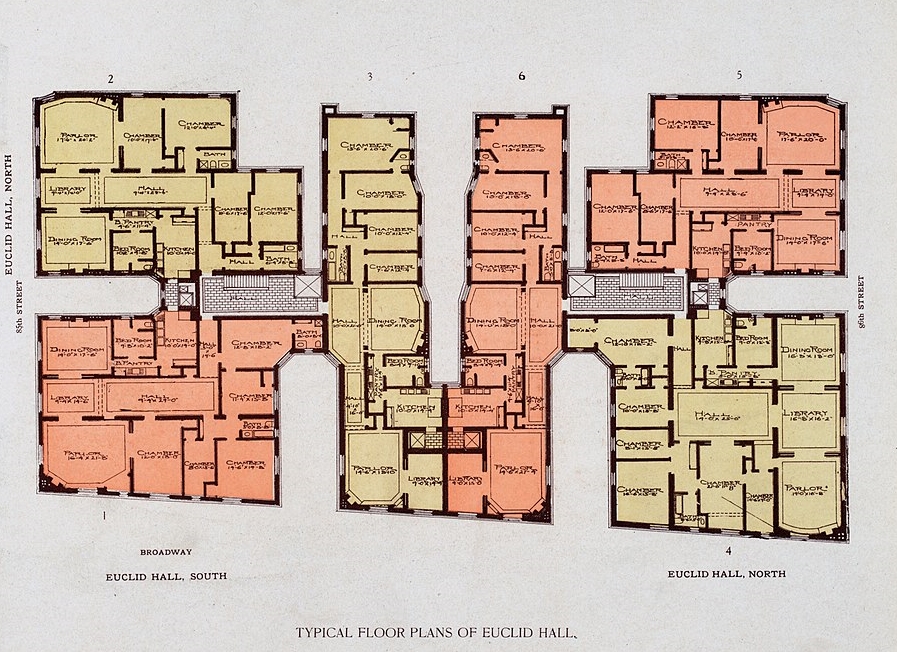

Le Grand K. Pettit intended his Euclid Hall to vie with other lavish Broadway apartment buildings. He directed that there be no stores along the ground floor—they would tarnish the upscale tenor of the building. Hill & Turner designed the building in a dignified take on the Beaux-Arts style, with less over-the-top ornamentation than the Ansonia and the Belleclaire, for instance. To provide ventilation and sunlight to all the apartments, the architects cut two deep light courts into the great mass of the building, giving it the initial impression of three separate structures.

Euclid Hall was completed in 1902. An advertisement touted it as “One of the Finest Apartment Houses on Broadway.” The apartments ranged from 9 to 12 rooms each, all with two bathrooms. The advertisement boasted in part:

Euclid Hall has been expressly designed to accommodate families accustomed to living in private houses. All rooms are of an unusual size and the private halls large enough to hold a dance in. These halls can also be thrown together with the adjoining parlor and dining room, thereby affording facilities for the entertainment of guests that are not equaled in many modern private residences.

Living in Euclid Hall was not cheap. The monthly rent for a large apartment would equal $7,500 per month today. The New York Times, on March 1, 1904, said “Although completed more than a year ago, Euclid Hall is still one of the most attractive of the upper west side apartment houses. One of the features of the building is the fact that, although it covers an area of about nine city lots, there are only three suites of apartments on each floor.”

All rooms are of an unusual size and the private halls large enough to hold a dance in.

Among the early residents were well-established artists. Living here by 1905 were painter Henry Mosler, his wife the former Sara Cahn, and their son Gustave Henry. Born in present-day Poland, Henry Mosler had been brought to New York City in 1849 when he was eight years old. After living in Paris for two decades, he brought his family back to New York in 1894, opening his studio in Carnegie Hall. By the time the Mosler family moved into Euclid Hall, Gustave Henry was an established artist, as well. His painting De Profundis won him a medal at the Salon in Paris in 1891.

Dr. William A. Drake and his wife moved into Euclid Hall in 1905, having lived previously on Central Park West. In addition to his private practice, he was a medical examiner for several life insurance companies. The Evening World said, “He enjoyed a handsome income from this and from his practice.” The Drakes had no children and lived happily until the doctor contracted facial neuralgia in October 1905, a condition causing bouts of searing pain, similar to an electric shock.

According to The Evening World, “Dr. Drake had been using morphine for some time in an effort to obtain relief from the well-nigh unendurable pains of his affliction.” At some time early in the morning of March 1, 1906, he got out of bed and went to his medical bag. Around 5:30 he returned to bed. But at 6:00 Mrs. Drake became alarmed at his unusually loud breathing and discovered he was unconscious. Unable to rouse him, she phoned Dr. Sinclair K. Royle, a good friend of her husband.

When Royle arrived, he found Drake “almost gone.” The 39-year-old doctor died of a morphine overdose shortly afterward. It was unclear whether he had committed suicide or died accidentally.

In 1910 the family of German-born Henry Mendelson lived here. The principal of the silk firm H. Mendelson & Co., Henry and his wife had two daughters and a son. But it seems someone wanted the Mendelsons out of Euclid Hall.

Just before midnight on the night of April 9, young William Mendelson woke up to find his room filling with smoke. He awoke his parents, and the three attempted to put out the flames, which were coming from a closet. Finally, they fled the apartment yelling, “Fire!” The New-York Tribune reported, “A mysterious fire which started in the apartments of Mr. and Mrs. Henry Mendelson…routed every family in the big house out of bed.” The elevator boy got all the residents to the ground floor safely. The newspaper said, “The flames rapidly ate their way through to the fifth and sixth floors, chasing Frank Presbrey and F. L. Strong from their beds. Ex-Senator Martin Saxe’s apartment was damaged.” Before the fire was extinguished it had done nearly $170,000 by today’s standards in damages.

On June 29, just before the Mendelsons left for their country home, a second suspicious fire broke out. The New-York Tribune reported, “the tenants of the fashionable Euclid Hall apartment house…spent a bad fifteen minutes early this morning while bellboys fought a small fire which started in the stuffing of a couch in the apartment of Henry Mendelson, a silk merchant.” This time the fire had been discovered early enough to control. The newspaper noted, “Tenants of the building who had watched the fire in scanty garments returned to their beds before firemen reached the building.”

Then, on the night of August 31 at 10:30, Mrs. F. L. “Jack” Strong, who lived directly above the Mendelsons, saw smoking rising through the floorboards. She telephoned the building superintendent, Thomas Groark, who banged on the Mendelsons’ door. When no one answered, he “seized the axe kept in the hall in case of fire and broke into the apartment.” William was asleep in his smoke-filled room, and the maid, Marie, was sleeping in hers. The Mendelsons had taken their daughters to the theater and were not yet home. The bedroom next to Williams was engulfed in flames. Groark ran to a window and yelled to a policeman to send in an alarm. “By this time the smoke was pouring out of the apartment, and the alarm had spread throughout the house,” said the New-York Tribune.

The bedroom in which this fire had started was filled with “valuable bric-a-brac, statuary and paintings and a piano,” which had been moved there while the damage from the previous two fires was being repaired. The arsonist was never discovered.

A socially visible family were the Bedell Parkers, living in a fifth-floor apartment at least by 1913. Parker and his wife, the former Cassandra (known as Sannie) O. Gaines, had a daughter, Frances Bedell. Like all residents of Euclid Hall, they spent their summers away from the city. They had a summer home in Lake Placid, New York, and a country estate, Wheatland, in Virginia.

Parker was the head of Delpark Corporation, a garment manufacturing firm. On the night of January 19, 1916, he was in California on business and Sannie was attending an event at the Hotel Astor. The maid, Emily, had put Frances, who was now 14, to bed, but sometime after midnight, Frances awoke to a cold draft. She got up to investigate and when she turned on the hall lights, she found a masked man crouching on the floor above a pile of valuables, about three feet from her.

The Evening World reported, “In their flight down the fire-escape the men made so much noise that they awakened other residents on the lower floors. The whole apartment house was soon in commotion.”

The irate girl demanded, “What are you doing here, you man?” He rushed into her mother’s bedroom where the window was wide open. Another man appeared from Emily’s room where the awakened maid had been petrified with fright. Frances screamed to rouse the neighbors as both men clambered out the window. The Evening World reported, “In their flight down the fire-escape the men made so much noise that they awakened other residents on the lower floors. The whole apartment house was soon in commotion.”

The heroic girl had prevented an expensive loss. The New York Press reported, “In the various rooms of the Parker apartment the police found many pieces of jewelry and other articles which had been bundled into sacks by the intruders.”

The days of maids and country houses were over at Euclid Hall by the time war broke out in Europe. The once-elegant building was now being operated as a single-room-residency hotel. The circumstances were reflected in a horrific incident on March 23, 1945.

Because tenants did not have telephones, they shared a common payphone in the hallway. Should they receive a call, the switchboard operator in the lobby would sound a buzzer in their room. At 1:30 that morning Samuel Zuckerman’s buzzer rang. He went into the hallway and as he picked up the receiver of the telephone, he was fatally stabbed in the back and slashed several times. When he did not return, his wife Dorothy went into the hall to check on him. Her screams were heard by the telephone operator downstairs. Police found an eight-inch carving knife next to the body.

An article by Mark McCain in The New York Times on November 20, 1988, described the sad condition of Euclid Hall. “A hodgepodge of stores spans the ground floor. The upper six floors are sliced into a single-room-occupancy hotel—a maze of crumbling rooms for people of limited means, some who have been there since the 1940’s and pay less than $50 a week for rent.”

Euclid Hall was purchased by the non-profit West Side Federation for Senior Housing in 1980. Four years later, the West End/West 85th Improvement Association discovered that the group had begun renovating the building “to bring in some residents with histories of mental illness and substance abuse.” A battle broke out over the fate of Euclid Hall, one that the West Side Federation for Senior Housing won. And in the end, the locals had to admit their fears were overblown.

The group hired Cetra/Ruddy Architects to renovate and restore the building, going so far as to sympathetically restore the fire escapes, matching the diagonal latticework and French motifs with the balcony ironwork. Completely renovated today, Euclid Hall provides permanent housing to more than 272 people.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

Building Database

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the business at 2345 Broadway:

Meet Bobby Santangelo!