The Alameda

by Tom Miller

Although Charles V. Paterno earned his medical degree from Cornell University in 1899, he did not practice. The son of real estate dealer John Paterno, he and his brother Joseph took over the Paterno Construction Company upon their father’s death. Although Charles never practiced medicine, he used the title Doctor for the rest of his life. On June 13, 1914, the Record & Guide reported that Dr. Paterno had commissioned Gaetan Ajello to design a “fourteen-story apartment house of the highest type” on the northwest corner of Broadway and 84th Street.

Paterno had chosen Ajello, in part, because of his patented Ajello System of reinforced concrete floor construction. It allowed for thinner, but equally strong floors. The Record & Guide pointed out that the savings of four feet would be “utilized in the height of the first floor stores on the Broadway side.”

Completed in 1915, the building was called the Alameda. Twelve stories of gray brick sat upon a rusticated limestone base. Ajello’s Italian Renaissance design featured multiple intermediate cornices and balconies, which relieved the visual mass of the structure. A modillioned cornice capped the design. The residential entrance was placed to the side, within a dignified Renaissance-style frame.

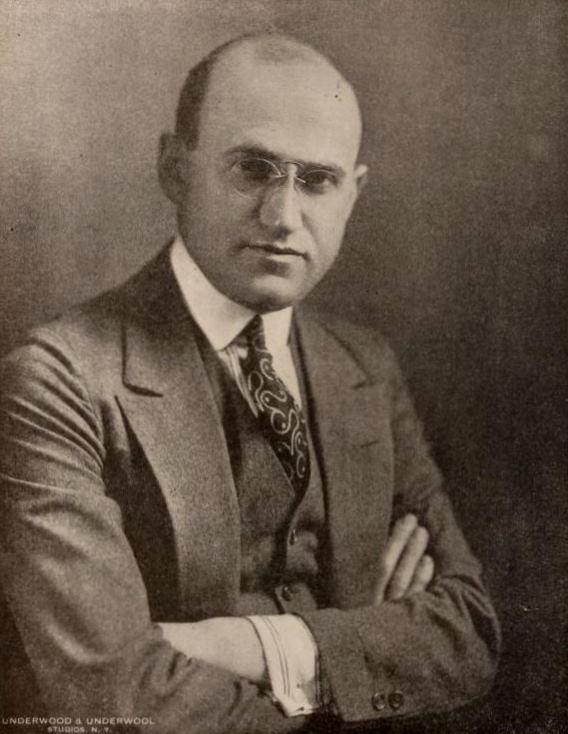

Among the first tenants was the recently divorced Samuel Goldfish. Born in Poland, he had anglicized his surname from Gelbfisz in 1898. He married vaudeville performer Blanche Lasky in 1910, and the couple had a daughter, Ruth. Goldfish’s philandering resulted in their divorce in 1915, the year he moved into the Alameda. Two years earlier, Goldfish had partnered with Blanche’s brother, Jesse Louis Lasky and Cecil B. DeMille, forming the Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Company to produce silent movies.

A year after moving in, Goldfish partnered with Broadway producers Edgar and Archibald Selwyn to form the film-making venture Goldwyn Pictures—a combination of the two surnames. In 1918 Goldfish legally changed his name again, this time to Goldwyn. Samuel Goldwyn’s motion picture success would continue to grow, his studio eventually becoming Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

In the meantime, the seven stores along Broadway were home to a variety of tenants. In 1915 they included Henry Nockin’s jewelry store, a phonograph store, and a dress shop. There were also the Alameda Tailor Shop, the Alameda Hair Cutting Parlor, and Mme. Helene French Dying and Cleaning store.

Samuel Goldwyn’s motion picture success would continue to grow, his studio eventually becoming Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

The residents of the Alameda were expectedly professionals. Among the early residents were John Francis Sullivan, a civil engineer with the city’s Board of Estimate and Apportionment; and Henry Bree Henson and his wife. Henson retired from the railroad business in 1916. For six decades he managed the Gould railroads and was secretary and treasurer of the Missouri, Kansas and Texas Railroad.

Cotton broker Isaac Gustofer, his wife and sister-in-law were also early residents. By 1919 their marital bliss had evaporated. Mrs. Gustofer was convinced her husband was cheating on her, and hired a private detective, Ralph H. Smith to follow him. On the night of November 30, 1919, things got heated in the Gustofer apartment, and the sister-in-law telephoned Smith in fear. The private detective rushed to the apartment and “laid hands on Mr. Gustofer,” as worded by the New-York Tribune. Gustofer had him arrested for assault. In night court Smith pleaded that he had entered the apartment and physically confronted Gustofer “only because he thought Mrs. Gustofer needed protection.” The magistrate found that he had no right to enter the apartment “no matter who asked him to do so,” and sentenced him to 10 days in jail.

The extended Stern family occupied apartments by 1920. I. Harold Stern, president of the Alaska Chemical Co., lived here with his wife, the former Lillian Ullman; Samuel Stern was managing director of the British Ever Ready Co. Ltd.; and S. Sidney Stern was in the lace and embroidery business.

Like all the residents of the Alamda at the time, I. Harold Stern had a country home—his and Lillian’s was in Tarrytown—and an automobile. Late on Saturday night, November 26, 1921, Stern received a disturbing telephone call. His touring car had been involved in a high speed police chase. The New York Herald reported, “After a chase by automobile from Yonkers to Irvington, about eight miles, two Yonkers policemen arrested James Britt, chauffeur for I. Harold Stern of 255 West Eighty-fourth street.” Stern, who had not authorized Britt to take the car, was not pleased. “Mr. Stern, when notified, asked that the chauffeur be held.”

Described by the Daily News as a “wealthy importer of laces and embroideries,” S. Sidney Stern was increasingly having problems with his wife at the time. Florence seems to have been a modern woman, unwilling to be subservient to her husband. It came to head in court on April 24, 1923. The Daily News reported that she was “suing for separation because her husband assumed a dictatorial manner toward her.” Stern was ordered to pay $300 a month in alimony until the settlement of the case ($4,750 today), and $700 counsel fees.

Henry Nockin still operated his jewelry store in 2321 Broadway at the time. In 1925 he installed a high-tech anti-burglary device. When a robber entered the store, the clerk could activate a foot lever “which instantly releases tear gas,” reported The New York Times. On August 13, a mock hold-up was staged to test the device. The newspaper wrote, “within a few minutes the supposed bandits had been rendered helpless, and many persons in the crowd watching the trial were rubbing their eyes and rapidly making off for more comfortable regions.”

Unfortunately, the thugs that targeted the store two months later, did not go inside. On October 19, 1923, Larter & Sons wholesale jewelers sent salesman John B. Sanford, with four cases of goods, valued at upwards of $1.6 million by today’s conversion, to the store. Sanford was driven by Arthur Franklin. Their sedan had been customized with a storage place for jewelry that replaced the rear seat. Unknown to them, they were being followed. Sanford went into the store to talk to Nockin while Franklin waited in the car. Suddenly “a big sedan of an expensive make,” as described by The New York Times, drove up. Six men jumped out and before Franklin had time to pull out the revolver he carried for protection, he was dragged from the car. He struggled until one of the men pressed a pistol against his side and threatened to “shoot him full of holes.”

Franklin, afraid to alert any of the passersby, was walked quietly down Broadway. The article said scores of people passed as the crooks removed the jewelry from one car to the other. Nockin’s innovative tear gas system could not prevent the massive jewel heist.

David N. Mosessohn and his wife were residents around this time. Born in Ekaturinoslav, Russia in 1883, his father had been the chief rabbi of Odessa. David was brought to America at the age of five. He earned a law degree in 1902, the same year he and his father started publication of The Jewish Tribune. Following his father’s death, he became the editor of that publication. He was, as well, the executive chairman of the Associated Dress Industries of America, which he formed during World War I to promote war drives. Mosessohn was only in his mid-50’s when he showed signs of arteriosclerosis. It worsened to the point that he was bedridden on December 14, 1930, and he died two days later at the age of 57.

[Michael Moore] explained, “she believes in keeping an eye on persons who are a threat to the country. So do we.”

In January 1988 the Alameda suffered an uncomfortable case of déjà vu. On September 10, 1925, a 20-inch water main at the corner of Broadway and 85th Street had burst. It “let loose a flood in the West Side subway,” reported The New York Times. The article noted, “Among the apartment houses with [its] cellar flooded was the Alameda Apartments…In the cellar of that house, the water rose almost to the level of the street.”

Now, on January 15, 1988, a 90-year-old water main broke at nearly the exact location. The New York Times reported that the break sent “a cascade of water flowing westward in the frigid darkness into basements of apartment houses and stores.” The Alameda was without power or telephone service 24 hours later—a distressing circumstance for the residents during the January cold.

A most colorful resident was literary agent and author Lucianne Goldberg. She played a key role in the impeachment of President Bill Clinton in 1998 by advising Linda Tripp to secretly record Monica Lewinsky over a 20-hour period. The tapes became crucial to Ken Starr’s investigation of the President.

The mother of conservative political commentator Jonah Goldberg and Republican nominee for New York City Council Joshua Goldberg, Lucianne claimed to have served on John F. Kennedy’s White House staff, although there are no records to prove that.

While The Washington Post called Goldberg “the producer and publicist” who set the gears in motion for the Clinton impeachment, she preferred to call herself a “facilitator” in the case. In frequent interviews, Goldberg defended her right to delve into people’s private lives based on their actions. Filmmaker Michael Moore reacted, setting up a webcam focused on Goldberg’s apartment. He called it the “I See Lucy Cam” and explained, “she believes in keeping an eye on persons who are a threat to the country. So do we.” In response, Goldberg sold advertisements placed in her window for $1,000 a week.

Other than the Broadway storefronts, the Alameda remains nearly unchanged—its dignified presence hiding its rich history.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

BUILDING DATABASE

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the businesses currently at 255 West 85th Street aka 2321-2331 Broadway:

Meet Misha Punwani!