The Overdene

by Tom Miller

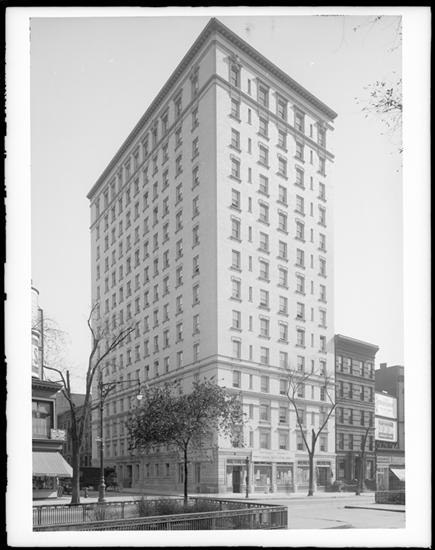

In August 1916 architect Gaetan Ajello filed plans for a 14-story apartment building at the southeast corner of Broadway and 105th Street for T. J. McLaughlin Sons. The gray brick and limestone structure would cost the developers $400,000 to construct—a considerable 10 million in 2023 dollars. Completed the following year, the New-York Tribune called the Overdene “upper Broadway’s tallest apartment building.”

The reserved Renaissance Revival style structure sat upon a rusticated limestone base on the 105th Street side, while the Broadway ground floor housed commercial spaces. Ajello relieved the building’s mass with a series of intermediate cornices that visually broke it into five sections. The understated residential entrance at 230 West 105th Street was sat within a simple, gently curved arch. On Broadway there were three stores and a bank, while inside were 71 apartments including a duplex with ten rooms and five baths.

The residents of the Overdene were professionals, like F. C. Schang. A recent graduate of Columbia University, he was the secretary and general manager of the Metropolitan Musical bureau, which “handles the extra operatic activities of Metropolitan Opera stars,” according to the Columbia Alumni News in 1918.

Carlos Restrepo was another early resident. Born in Colombia, South American and educated at Cambridge University, he established the Engineering and Exporting Company, was vice-president of the Leonard Exploration Company, and with his son Luciano organized the Tropical Oil Company.

The wives of the affluent businessmen busied themselves with charities and clubs. Anna Maxwell Jones was among the more visible. She was the State Chairman of Civic Art for the Federation of Women’s Clubs. In 1918 she headed a protest in Albany “against legislation affecting scenic beauty; [and] efforts to prevent objectionable posters outside of motion picture theaters.” The group also recommended “furthering landscape gardening.”

The Morning Telegraph reported on October 15 that he had left Amy everything within the apartment, “his automobiles,” and a trust fund of $200,000 (about $3.25 million today).

Anna Maxwell Jones was not alone. The 1920 Club Women of New York listed four other residents who were involved in a variety of clubs. (F. C. Schang’s wife was secretary of the Book and Thimble Club of Manhattan.)

Nathan Blyn and his wife, the former Amy Goodhart, lived in the Overdene at the time. Nathan was a partner in the shoe manufacturing firm Blyn, Inc. The couple had two adult children, Henry and Rose, and an adopted daughter Clara, all of whom were married. Nathan and Amy were summering at Rockaway Park, New York in 1922 when then 56-year-old died. His will would raise eyebrows.

The Morning Telegraph reported on October 15 that he had left Amy everything within the apartment, “his automobiles,” and a trust fund of $200,000 (about $3.25 million today). An apparent rift between Blyn and Clara Blyn Meth became evident in the will. He divided the rest of his estate between Rose and Henry, and his brothers and sisters. No mention was made of his adopted daughter, “nor is any explanation given for omitting her from same,” said the article.

The most colorful resident of the Overdene was Gottfried (Fred) Walbaum, who lived in apartment 10-A with his second wife, Mary Agnes Tierney. The pair had married one month after he divorced his first wife in May 1899. Walbaum was well-known for operating racetracks (reportedly shadily), gambling parlors and brothels.

His famous gambling house was at 33 West 33rd Street, known as the Bronze Door because of the door through which patrons passed. When Walbaum closed the parlor and auctioned off the furnishings on September 13, 1917, the door was described in the brochure as “The wonderful real sculptured bronze door from the wine cellars of the Dodges [sic] Palace in Venice.” A reporter from The Sun was surprised at the seemingly low price it brought, saying, “this beautiful and priceless door, which has looked down upon the gambling revels of some of the wealthiest men and the wiliest politicians of the nation, was knocked down for the bagatelle of $1,000.”

Also sold was the canvas ceiling of the main gambling room on the second floor designed by Stanford White. It was purchased by Pierre Cartier. The staircase, also designed by White, “took the labor of eight Swiss carvers for two straight years” to create. Paintings, rich furnishings, and other items brought what the reporter deemed low prices. But, he said, “Gottfried Walbaum, fat, white haired, with deep lines around his mouth and pendulous bags under his inscrutable eyes…has a cool $7,000,00 or $8,000,000, and no one but his wife to take care of, so he can afford to lost on this sale.”

In 1922 Walbaum and his wife prepared to move permanently to Ormond, Florida. An auction of their “sumptuous furnishings” was held in the apartment on September 26. The announcement said, “The appointments of this apartment are of unusual splendor and recently made to special order by some of our best known cabinet markers and decorators.” Included was a Queen Anne dining room suite, a Louis XVI living room set, Flemish tapestries, a collection of oil paintings by “eminent artists,” and on and on.

Also living in the Overdene was piano manufacturer Walter C. Hepperla. Born in Baltimore in 1876, he “exclusively pioneered the idea of the small Grand Piano,” according to Herringhaw’s American Blue-Book of Biography in 1923. The article noted “He is president of the Premier Grand Piano Corporation, the largest of its kind in the world, of which he was the organizer.”

By the early 1940s Sara Ornstein lived here. She drew the attention of the United States Congressional committee in 1944 that was investigating “Communist activities among aliens and national groups.” It was understandable that they would notice her–she was the membership director of the Connolly Branch of the Communist Party. Sara would live at the address well into the 1950s.

The staircase, also designed by White, “took the labor of eight Swiss carvers for two straight years” to create.

The store at 2372 Broadway was home to Paul W. La Sota’s jewelry store in 1952. On December 16, three gunman walked in and robbed La Sota of $25,000 in goods—more than a quarter of a million in 2023 dollars. Two days later, detectives received an anonymous telephone tip. The New York Post reported, “Police today…recovered jewelry worth up to $15,000, part of the $25,000 haul.” The article said, “detectives discovered the loot in a locker in the IND subway arcade at Sixth Av. And 42d st. La Sota identified the jewelry.”

When the building was converted to co-ops in the second half of the 20th century, the name was dropped in favor of the address. A 1998 renovation resulted in 70 apartments, including the duplex on parts of the fourth and fifth floors.

The COVID pandemic prompted the owners to make what most would see as a generous move. To help the struggling businesses on Broadway—a coffee shop, a deli, an apparel store, and a shoe repair shop—they discounted the commercial rents. And to make up for it, the board raised the owners’ maintenance fees 15 percent.

While Gaetan Ajello’s handsome Italian Renaissance-style building can no longer boast of being “upper Broadway’s tallest apartment building,” it remains as dignified as it was in 1917.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

BUILDING DATABASE

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the businesses currently at 2730-2738 Broadway aka 230 West 105th Street:

Meet Jim Rasenberger!