(NOT) General Tecumseh’s Home

by Tom Miller

In April 1887, real estate developer Joseph T. Farley commissioned the architectural firm of Thom & Wilson to design seven four-story houses on West 71st Street anchored by a five-story apartment building on the northeast corner of Ninth Avenue (soon to be renamed Columbus Avenue). The apartment building would cost Farley the equivalent of just over $1 million by 2023 terms.

For that building, the architects blended the Romanesque Revival and Renaissance Revival styles, adding a touch of Gothic Revival in the pointed arched windows of the ground floor of the 71st Street side. The entrance sat atop a dog-legged stoop at 87 West 71st Street. The address would be changed to 75 West 71st Street in 1892.

(Incidentally, the change of addresses along the 71st Street block would cause confusion for amateur historians forever after. Among the initial residents of Farley’s row of houses were General Tecumseh Sherman and his wife Eleanor. They purchased 75 West 71st Street, which was five houses east of the apartment building. A year after he died in 1891, the address became 63 West 71st Street. For decades historians who read his 1891 obituaries listing his home at 75 West 71st Street have presumed he lived on the corner.)

There were two apartments per floor in the building. An advertisement in 1893 boasted apartments of “7 extra large and sunny rooms and bath; seam heat; rents $55 and $65.” The rents would translate to between $1,710 and $2,000 per month today.

In 1899 the Brooklyn Daily Eagle newspaper opened a new Manhattan branch office at 241 Columbus Avenue.

The commercial spaces along the avenue filled with offices. In 1893 the F. S. Williams stationery store was in 241 Columbus Avenue, Horman Bostwick’s real estate office was at 243 Columbus Avenue, and next door at 245 Columbus Avenue was the J. Romaine Brown & Co. real estate office. James Van Dyck Card was a member of the latter firm. Like Horman Bostick, he was ardently interested in the Upper West Side and on March 1897 held a meeting of the Committee on Public Safety of the West End Association in his office here. In reporting on the upcoming gathering, The New York Times said it would be “another attack on Col. Waring for his failure to remove ashes in the upper part of the city, and for his determination to erect a still dump on the upper west side.”

In 1899 the Brooklyn Daily Eagle newspaper opened a new Manhattan branch office at 241 Columbus Avenue. It would remain there at least through 1910. J. Romaine Brown & Co. was replaced in 245 Columbus Avenue by a steamship ticket office in 1903.

Living in a fourth-floor apartment in 1913 was Mabel Conant, a dressmaker. The unmarried woman had two houseguests over the Christmas holiday that year, Lillian Pearce and Lila Sanford. On the night of December 26, Mable and Lillian went out, leaving Lila at home alone. She went to bed sometime before 9:00. As she slept, a fire broke out in the furnace room in the cellar. A policeman, noticing the smoke, rushed the basement where a porter was trying vainly to put out the flames. But when Officer Hardiman opened the door to the room, the rush of oxygen cause a backdraft. According to The New York Times, the air was what the blaze needed “to send flames up through the building, and to allow the fire to mushroom on the top floor.”

Forced to leave the porter behind, Officer Hardiman managed to get out. In the meantime, the fire escapes on Columbus Avenue were filling with residents. The New York Times reported, that Hardiman “rushed upstairs, spreading the alarm as he ran. Women and children were racing through the halls, and the smoke was getting thicker every moment.” Finally, he ducked into a vacant apartment on the fourth floor “to save himself,” unaware that Lila Sanford was still in the other apartment on that floor. Leaning out the window, he continually entreated the families on the fire escapes not to jump, promising them that firefighters were en route.

The first responders carried women and children down ladders and helped other victims off fire escapes. When the blaze was controlled enough to enter the building, they began a search. The Troy Times reported that they “found Mrs. Sanford in the Conant parlor, suffering great pain and trying to get to a window.” Before they could get her out of the apartment she lost consciousness. Dr. Harry Archer of the fire department worked on her for more than an hour on the street, but she succumbed to burns and smoke inhalation. The porter, who had been trapped in the furnace room, was incinerated.

The substantial repairs to the building took months to complete. In September 1915 an advertisement touted, “Corner Apartment, 75 West 71st; seven large, all light rooms and bath, $57.50; building newly constructed; electric lighting; parquet floors.”

The building’s janitor, William Reese, resided in a small apartment in the basement level in 1920. Tragically, on June 15 he was discovered dead on his sofa dead. The Evening World reported, “It is believed the gas stove was accidentally turned on.”

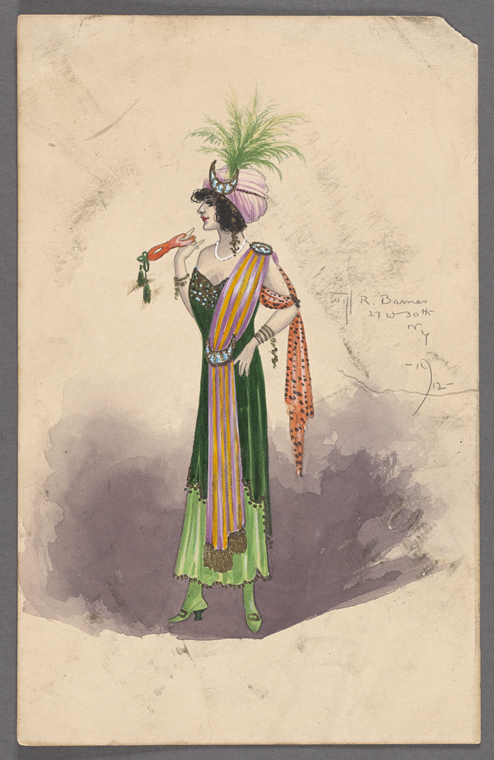

A notable resident during the Depression years was Will R. Barnes, a landscape watercolorist and costume designer.

A notable resident during the Depression years was Will R. Barnes, a landscape watercolorist and costume designer. Born in Australia, he studied at the Fitzroy School of Design in Melbourne. He arrived in New York City in 1899 as a costume designer, creating costumes for the Hippodrome and the Metropolitan Opera Company. He worked occasionally with composer Reginald De Koven, designing the costumes for his musical plays Robin Hood, Rob Roy, and Rip Van Winkle.

The Columbus Avenue commercial spaces that had been offices throughout the building’s early decades were home to retail shops by the third quarter of the 20th century. In 1975 the Holding Company, a women’s accessories shop, opened in 243 Columbus Avenue and would remain for a decade. Another boutique, Arlequin, was in 245 Columbus Avenue by the 1980s.

After having been on Christopher Street in Greenwich Village since 1895, McNulty’s Tea & Coffee Company opened a store at 247 Columbus Avenue. In reporting on its opening on January 8, 1992, The New York Times’s food critic Florence Fabricant noted, “The slightly larger uptown store has the warm, woodsy look of the original.” Harry’s Burrito Junction opened in 241 by 1993, and in July 2010 Paige Denim, an apparel store, opened in 245.

The building’s ground floor has been monstrously brutalized, the charming crooked stoop removed, and the red brick and contrasting stone of the upper floors painted white. Despite the architectural desecration, Thom & Wilson’s dignified 1887 design still greatly survives.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com/

LEARN MORE ABOUT

241-247 Columbus Avenue

Keep

Exploring

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 241-247 Columbus Avenue aka 75 West 71st Street:

Meet Doris, Coco and Monica!