160 West 74th Street

by Tom Miller

Born in Paris, France on January 8, 1856, Louise Veltin was brought to America by her parents at the age of 7. Her father, Christian Veltin, joined the U.S. Army. He was killed in the battles with the Native Americans in New Mexico. Her mother, Henriette de Launay Veltin, ensured that Louise received a sterling education.

In 1886 Louise Veltin opened a private girls school at 175 West 73rd Street. It was highly successful and just six years later in April she purchased “for improvement,” property on the south side of West 74th Street, just west of Amsterdam Avenue as the site of a new school building. Veltin paid $31,106 for the properties, around $1 million in today’s money, which held two wooden buildings–one two stories tall and the other one story high.

The prolific firm of Lamb & Rich was given the commission to design the replacement structure. The architects produced a formal, neo-Georgian style structure appropriate for the respectable institution it would house. Originally four stories high above a basement level faced in rough-faced stone, it was clad in ruddy red brick. A wide stoop led to the first floor where alternating rows bands of brick and stone created a striated effect. A stone balustraded balcony at the second floor fronted two windows which wore classical pediments. A Greek key frieze ran below the cornice.

Mademoiselle Veltin’s Day School for Girls opened in its new home on October 5, 1893. An advertisement boasted that the “modern fireproof building” contained “assembly hall, study rooms, class and recitation rooms, laboratory, studio, and gymnasium with ventilated locker for each student.”

Unlike many private girls’ schools, which focused on preparing wealthy young women for lives in society, the Veltin School was already known for its much wider curriculum. Girls could study courses such as astronomy, physiology and physics–normally offered only at male institutions. Louise Veltin hired well-known instructors. Clara and Frank Damrosch, for instance, oversaw the music department and among the art instructors was American Impressionist Robert Henri.

It was not long before the new school building could not accommodate all the applicants. In 1899 Louise Veltin brought Charles A. Rich back to “raise” the building, as described in his plans. The $12,000 renovation resulted in an additional story which took the form of a metal-clad mansard roof. Simultaneously, an elevator was installed, bringing the total construction costs to the equivalent of $421,000 today.

Girls could study courses such as astronomy, physiology and physics–normally offered only at male institutions. Louise Veltin hired well-known instructors. Clara and Frank Damrosch, for instance, oversaw the music department and among the art instructors was American Impressionist Robert Henri.

Early in the 20th century still more space was necessary. The school expanded into a rowhouse directly behind the school at 165 West 73rd Street. The annex, known as Senior Hall, was connected to the main building by a “wide corridor,” as explained in an advertisement. That building, devoted to the Senior Department, contained “a large reference library and complete appliances for illustrating the various subjects.”

An advertisement in Educational magazine in 1908 hinted at the social and financial status of the Veltin School students. “Students are admitted at any age and are prepared for admission to Bryn Mawr, Vassar, Barnard, Wellesley and other colleges,” it said. By now the Art Department was a major feature of the school, taking up an entire floor of the main building. Its aim, said the advertisement, “is to awaken the mind of the student to the beauty in nature and art, to stimulate the creative faculty and to train the eye, hand and memory.” It noted, “Students in the Art Department come from all parts of the United States.”

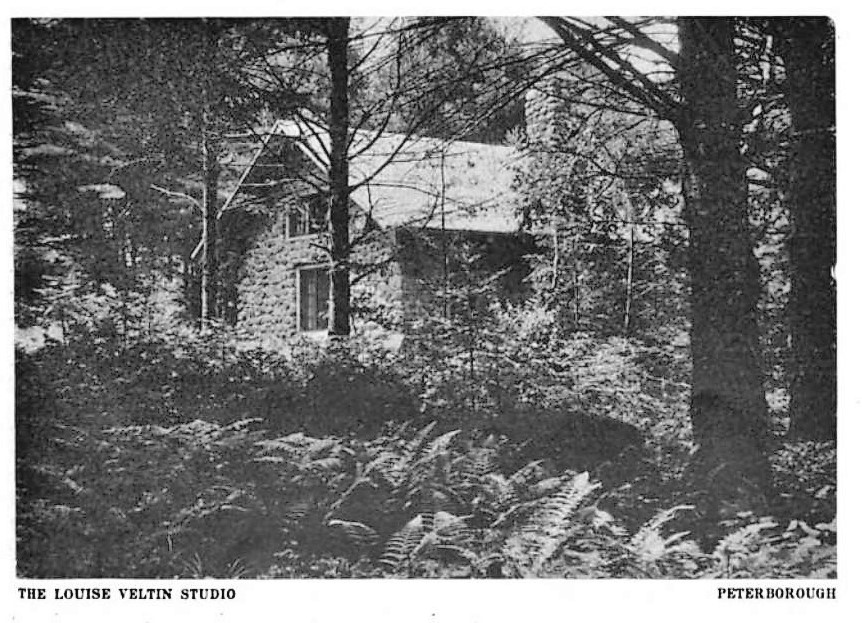

In 1912, the alumni of the Veltin School donated funds to establish the Louise Veltin Studio in the MacDowell Colony in Petersborough, New Hampshire. There were about 14 other studios on the 500-acre property, where pupils studied art or music. In 1915 The Best Private Schools described the Veltin School, saying in part, “It has an established reputation for the thoroughness of its college preparatory work, and in the past two years twenty girls have entered Vassar, Bryn Mawr, and Barnard in about equal numbers. Day pupils only are received. The teaching of French and art in this school is especially noteworthy.”

In April 1915, two years before America would enter World War I, the affluent students showed their support of the Red Cross by donating an ambulance. The New York Times reported it would “be marked with the name of the school and sent abroad,” adding, “All the money contributed by the girls was directly obtained by them through self-denial or actual labor.” The article noted further, “In addition, the older pupils have made, during the Winter, hospital garments and other supplies for war relief and the younger classes have made bandages.”

A surprising ceremony took place in the auditorium that year. On November 2, The New York Times reported, “The wedding of Victor Starzenski, a son of the Countess Anna Starzenski and the late Count Maurice Starzenski, and Miss Hilda Sprague-Smith, the daughter of Mrs. Charles Sprague-Smith and the late Charles Sprague-Smith, was celebrated at 4:30 yesterday afternoon in the Assembly Room of the Veltin School, 160 West Seventy-fourth Street.” The lavish ceremony included the full vested choir of the Church of the Ascension, and the auditorium was transformed by potted palms, ropes of laurel tied with white ribbons, and a profusion of white chrysanthemums.

On August 2, 1924, The New York Times reported, “Louise Veltin sold the Veltin Girls’ School, a modern fireproof school building, at 160 and 162 West Seventy-fourth Street, running through to 163 and 165 West Seventy-third Street…to the De La Salle Institute, a boys’ school.” The Roman Catholic high school, conducted by the Brothers of the Christian Schools, had been on West 59th Street since 1902. The institution paid $500,000 for the property–closer to $14.5 million today. Changes were made to the 73rd Street buildings by installing a chapel and faculty residence.

The De La Salle Institute operated from the buildings for 36 years. Then, on July 9, 1960, The New York Times reported that it had sold the buildings to realty investor Fred H. Hill. The article explained, “The institute was closed with the term just ended because the Christian Brothers decided that it would be too costly to modernize the buildings for school purposes.” Fred H. Hill announced his intentions to convert the 73rd Street property “into an apartment building,” while leasing the main Veltin School building “to an institution.”

That institution was the Baldwin School, a private, coed academy that stressed the arts in addition to conventional academic studies. A decade after moving into the building, the Baldwin School merged with three other private schools–the Columbia Grammar and Preparatory School, the Elisabeth Irwin High School, and the Walden School–to form the Independent School Council of New York City, Inc. Each retained its independent identities and continued to operate from its own facility, but the merger provided logistical opportunities.

“The four schools, may, for example, share one teacher in a field such as drama,” said the article. Dr. Rollin P. Baldwin, director of the Baldwin School, added that the directors hoped to attract teachers expert in studies “closely related to contemporary urban life, but outside the usual academic program.” Those would include “pollution, racism, politics, revolution, war, peace and censorship.”

That institution was the Baldwin School, a private, coed academy that stressed the arts in addition to conventional academic studies.

Teaching gymnastics here in 1976 was Danish-born Sus McCready, wife of actor Tom McCready. The couple had been married in July 1975 and Sus was awaiting approval for a green card signifying her permanent residency. On June 21, 1976 Tom McCready was on his way home to their Greenwich Village apartment when he saw a gang of teens attempting to break into a friend’s vehicle. He intervened and was fatally stabbed.

Now, in August 1976, the 29-year-old widow faced deportation “because, in the words of immigration officials, the marriage no longer exists,” said The New York Times. Henry Wagner, regional director of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, told The New York Times her petition “might be approved if she could show that “there are no American citizens qualified and able to fill the position she holds.”

The 14-year-old who was charged with the murder was out on bail. Sus McCready told the reporter, “I think about that little boy jumping around in Little Italy, and then I think why is it that he has more right to live in the United States than I have.”

Around 1990 the Calhoun School replaced the Baldwin School in the 74th Street building. The school’s 2nd through 12th grades were housed at 433 West End Avenue. This facility catered to three-year-old through first grade students. Like its predecessor, The Calhoun School garnered extra income from plays staged in the school theater. In October 1991, for instance, playwright Nancy Hasty’s Bobbi Boland was produced in the Calhoun School Theater with admission costing $10.

In 2022 the Calhoun School merged with the Metropolitan Montessori School, prompting the combined facilities to look for a new home. In August the venerable Veltin School building was placed on the market “in the mid-$20 million range,” according to realtor John Ciraulo of Cushman & Wakefield. The firm marketed the property as “the ripe opportunity for a boutique residential conversion or as a single-family mansion.”

UPDATE: 160 West 74th Street was sold to Bayrock Capital, an investment firm, in 2023 with the non-profit organization Volunteers of America planning to operate at the site.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com