171 West 57th Street, The Briarcliffe

by Tom Miller

Charles K. Eagle and his wife, the former Thecla Jensen, lived in the Rodin Studios at 200 West 57th Street in 1919. The two-year-old building contained large apartments that were flooded with natural light. But it did not have outdoor space—something the Eagles were passionate about. An article in The New York Times on June 15, 1924, quoted Charles Eagle as saying, “My wife and I have always loved the country and growing things, flowers and birds. Why should we have to leave town in search of things that made us happy?”

To remedy the situation, Eagle acquired the property abutting the Rodin Studios at the northeast corner of 57th Street and Seventh Avenue and hired the architectural firm of Warren & Wetmore to design a 13-story apartment building on the site. The Briarcliffe was completed in 1922. The entrance within the otherwise stoic two-story base featured a carved festoon that dripped delicate bellflowers and two bas-relief cameos that were encircled by carved fronds. Like the base, Warren & Wetmore’s brick-faced upper floors were nearly free of decoration except a stone balcony on the 57th Street side and two panels with swags.

An advertisement in March 1922 offered apartments “of 6 & 7 Rooms, 3 baths,” noting, “large light rooms, unusual closet space, and every modern appointment.” Rentals started at $5,000 per year—about $7,500 a month in 2024 terms.

One apartment stood out. Charles and Thecla Eagle’s 10-room, 6,000-square-foot penthouse had a ballroom-sized “solarium” with three doors that led to the 2,000-square-foot terrace. There were three bedrooms, a tearoom, a morning room, and a private gymnasium. (The New York Times described the gymnasium as being “an exceptionally well equipped one,” the walls of which were “decorated with trophies of the hunts [Eagle] had made.”

Charles Eagle had steel beams installed to support the tons of soil necessary for their garden. When completed, it had Japanese pines, flower beds, a fountain and pond with speckled trout, birdhouses, and live pheasants and squirrels.

It was the Eagles’ terrace however, that impressed. Charles Eagle had steel beams installed to support the tons of soil necessary for their garden. When completed, it had Japanese pines, flower beds, a fountain and pond with speckled trout, birdhouses, and live pheasants and squirrels. Eagle told a New York Times reporter they conceived of the rooftop Eden while traveling. “When we were last in California, we dreamed a dream,” he said.

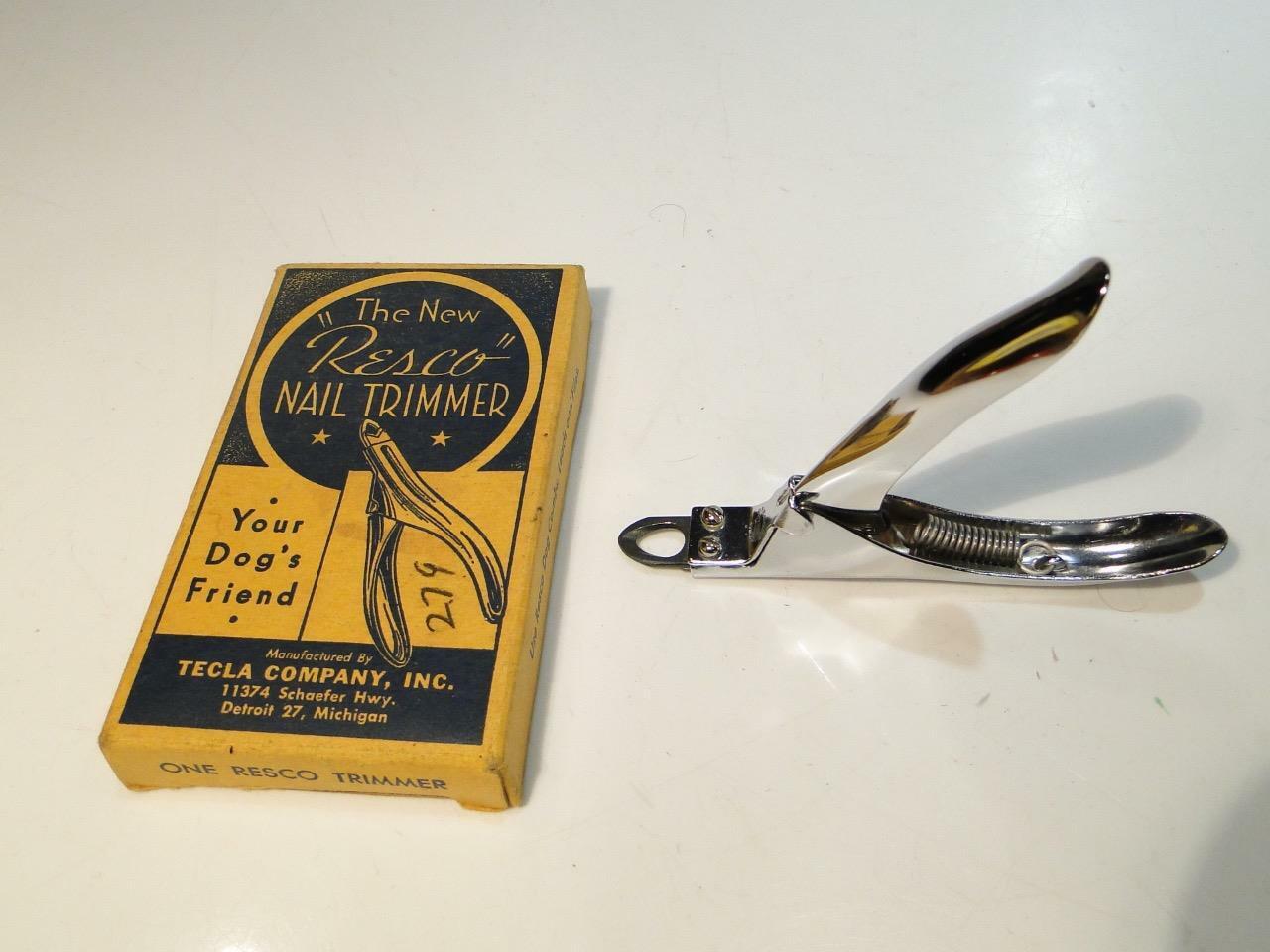

The ground-floor shop became home to Thecla Eagle’s cosmetic shop, Salon Tecla. (She, perhaps, dropped the “h” to ensure the correct pronunciation of the name.) Her creams and lotions were handsomely packaged with the name “Tecla.” Unfortunately, there was already a cosmetics manufacturer, The Tecla Corporation, that owned the copyright to the label. In June 1925, Thecla Eagle was sued.

It may have been the lawsuit that led to Thecla Eagle’s nervous breakdown. A live-in nurse, “Miss Marcellus,” was hired to care for her. The suit may also have been responsible for her husband, Charles’s selling the Briarcliff in August 1928 (although The New York Times said, “his business affairs were flourishing”). A few weeks after selling the building, at 11:00 on September 1, Eagle bid his wife good night. Thecla later recalled that when he came into her room, “he asked about her condition and told her not to worry.” He then went to his bedroom.

At around 9:00 the following morning, Miss Marcellus set the breakfast table and got Thecla up. When Charles did not appear, the nurse went to get him. She finally found him in the gymnasium, where he had placed a double-barreled rifle to his head and fired. In reporting on the suicide, The New York Times mentioned, “The penthouse apartment of the dead man was unusually elaborate, and adjoining it was a large garden filled with shrubs, ivy and other greenery.”

The Briarcliffe became part of architectural history in 1931. That year, architects Philip Johnson and Alfred Barr staged what Hugh Howard called in his 2016 Architecture’s Odd Couple, “their own antithetical salon des refusés.” Roger Kimball, writing in The New Criterion in November 1994, explained that because the Architectural League of New York had ignored promising young architects in their annual exhibition, Johnson and Barr “mounted an exhibition of ‘Rejected Architects’ on the pattern of the famous Salon des Refusés of 1863.” The exhibition was held in Thecla Eagle’s former cosmetics salon.

In September 1943, Allen Meltzer, the publicity executive for Warner Bros. signed a lease. He was, perhaps, the first of what would be a long list of residents from the entertainment industry. In the late 1940s, librettist and lyricist Dorothy Fields moved in. The daughter of famous vaudeville comedian Lew Fields, while living here, she worked on at least three Broadway musicals—Arms and the Girl, produced in 1950; A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, which opened the following year; and Beautiful Sea, in 1954. (She would be best remembered, perhaps, for her lyrics to the 1946 Annie Get Your Gun.)

Dr. Milton Berliher and his wife Hope lived here at the time. Hope was the public relations counsel for many opera stars, including Grace Moore, Lily Pons, Jeanette MacDonald, Mauritz Melchior, Bruno Walter, Elisabeth Rethberg, and Rose Bampton.

Among the guests at the dinner party the Berlihers hosted on St. Patrick’s Day 1956 were Broadway columnist Leonard Lyons and his wife Sylvia. The couple left around 11:30, and as they stepped out of the elevator into the lobby, they encountered chaos. Comedian Fred Allen was lying on a bench. Robert Taylor, in his Fred Allen – His Life and Wit recounts, “while someone tried to force a nitroglycerine pill through his lips, [someone] called an ambulance.” Allen had suffered a heart attack outside the doors of the Briarcliffe. He was pronounced dead in the lobby at 12:05 a.m.

Samuel Chotzinoff and his wife, Pauline Heifetz (the sister of violinist Jascha Heifetz), were celebrated residents. He was a confidante of Arturo Toscanini and “friend of many famous musicians,” according to The New York Times, which described him as “a music critic, a pianist, a novelist, a playwright, a raconteur, a wit, and an urbane and gentle man.” Born in Czarist Russia, Chotzinoff began studying piano at the age of 10. He was engaged by Efrem Zimbalist as the violinist’s accompanist when he was 21 years old. Remembering his early years in the Lower East Side, he founded the Chatham Square Music School.

Pauline Chotzinoff was also an accomplished pianist who was praised by Arthur Toscanini, according to The Times. Born in Vilna, Lithuania, she came to the United States in 1917. Samuel died on February 11, 1964, at the age of 74, and Pauline died in their Briarcliffe apartment on August 3, 1976, at the age of 73.

He was a confidante of Arturo Toscanini and “friend of many famous musicians,” according to The New York Times, which described him as “a music critic, a pianist, a novelist, a playwright, a raconteur, a wit, and an urbane and gentle man.”

Florence S. Anspacher was among the Chotzinoffs’ neighbors. The widow of playwright, poet and lecturer Louis K. Anspacher, she saved Joseph Papp’s New York Shakespeare Festival in 1959 after Parks Commissioner Robert Moses demanded that fees be charged to repair the potential damage to Central Park. Papp insisted that the program be free, and so in June it was announced that there would be no performances. Florence Anspacher stepped up with a $10,000 contribution to pay for Moses’s maintenance bill. She became increasingly involved with backing Papp’s cultural enterprises and was the largest private contributor to the restoration of the Astor Library Landmark Building.

Talent agent David Hacker was president of Lansdale Artists management, which he ran from his apartment. Before starting his own firm, from 1945 to 1963, he was vice president of the Music Corporation of America. Over the years he represented stars like Rosaline Russell, Rex Harrison, Ethel Merman, Leonard Bernstein, and Julie Andrews.

In the meantime, the Eagles’ sumptuous penthouse apartment had been home to party organizer and publisher of The Celebrity Bulletin Earl Blackwell since the 1940s. In the 1950s, he had the 18-foot-high walls of the salon decorated with “Venetian style” murals depicting classical garden scenes. Blackwell died on March 1, 1995, at the age of 85. On February 29, 1998, Tracie Rozhon of The New York Times reported the building’s owners had commissioned Richard Rice Architects to do a $500,000 restoration of the penthouse, including the murals. She noted that recently, the apartment had been shown “to Puff Daddy, the rap artist, and to agents for Donna Karan, the fashion designer.”

Sadly, the following year, the building was converted to a condominium, and the new penthouse owners did a “total reconstruction,” which “swept away” the murals, as reported by The New York Times columnist Christopher Gray in 2007. At the time, the newest owner, former Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross, had brought in Mario Buatta to supervise “more renovations.”

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com