The Sharon, 2 Manhattan Ave.

by Tom Miller

In 1904, 29-year-old developer Robert M. Silverman initiated construction of four apartment buildings that would fill the eastern blockfront of Manhattan Avenue from 100th to 101st Streets. Three of them would fill the southern half, while the fourth would engulf the entire northern portion. Designed by George F. Pelham in the Renaissance Revival style, the project was completed in 1905. The corner building, named the Sharon, included stores along the sidewalk. Pelham trimmed the red brick façade with limestone—splayed lintels, quoins, and Renaissance-inspired arched pediments.

Apartment Houses of the Metropolis described the apartments, saying in part,

The trim is of selected hardwood. Dining rooms are in Flemish oak with high panel wainscoting and Dutch stein shelf. Apartments are equipped with all the comforts and conveniences of the highest grade apartment buildings, nothing but the latest and best materials being used.

Among those conveniences were, “a U. S. mail chute, long distance telephone in each apartment and wall safes are installed. The electric elevator is noiseless and of the best construction.” Rents began at $480, or about $1,425 per month in 2025.

Among the earliest residents were insurance broker Arthur G. Marshall, his wife, and their nine-year-old daughter. Marshall was a partner with Frank D. Dunbar in the Duquesne Mutual Fire Insurance Company, the Lafayette Mutual Fire Insurance Company and the North American Mutual Fire Insurance Company.

He leaned the ladder against the fire escape and was quickly inside the Marshall apartment.

A shocking message was wired to The New York Times from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on September 4, 1905, that began, “A warrant was issued here for Marshall’s arrest about ten days ago, the charge being embezzlement.” (In fact, the warrant also included a charge of obtaining money under false pretenses.) At the same time, a warrant was issued for Frank D. Dunbar. According to the warrant, Marshall and Dunbar had “conducted a fake insurance business and did a business of nearly $2,000,000, much of it in and about New York. They did not pay claims and are alleged to have sold bogus stock.” Pittsburgh detectives had tracked Marshall to the Sharon apartment and alerted the New York Police Department.

On the night of September 4, Detective Sergeant McConville rang the Marshalls’ bell. The New York Times reported, “he got no reply, although he knew Marshall was in.” McConville was alone and was afraid that Marshall would escape through various exits in the building. He found the janitor, showed him his badge, and said, “There’s burglars on the top floor. You stand guard here until I get help.” The New York Times recounted, “’The devil a burglar’ll get by me,’ he said as he planted himself in the hall.”

McConville went upstairs, hoping to find a family who would let him climb down the fire escape to Marshall’s apartment, but everyone was out. Across the street was a construction site where McConville commandeered a 15-foot ladder (“despite the protests of the night watchman,” according to the article). He leaned the ladder against the fire escape and was quickly inside the Marshall apartment. Mrs. Marshall was absent. The janitor’s wife agreed to take in the little girl as Marshall was placed in handcuffs. The New York Times reported, “Marshall asserted that his arrest was all a mistake, and that the whole matter could be explained readily this morning.”

Apparently, he was correct. Marshall was extradited to Pittsburgh, where he stood trial. On November 18, The Buffalo News reported that the jury acquitted him of the charge of “swindling to the amount of almost $2,000,000,” but he was ordered to pay the costs of the trial. The article said, “Marshall said he thought the other side should have been made to pay the costs, but that he felt satisfied with the outcome.”

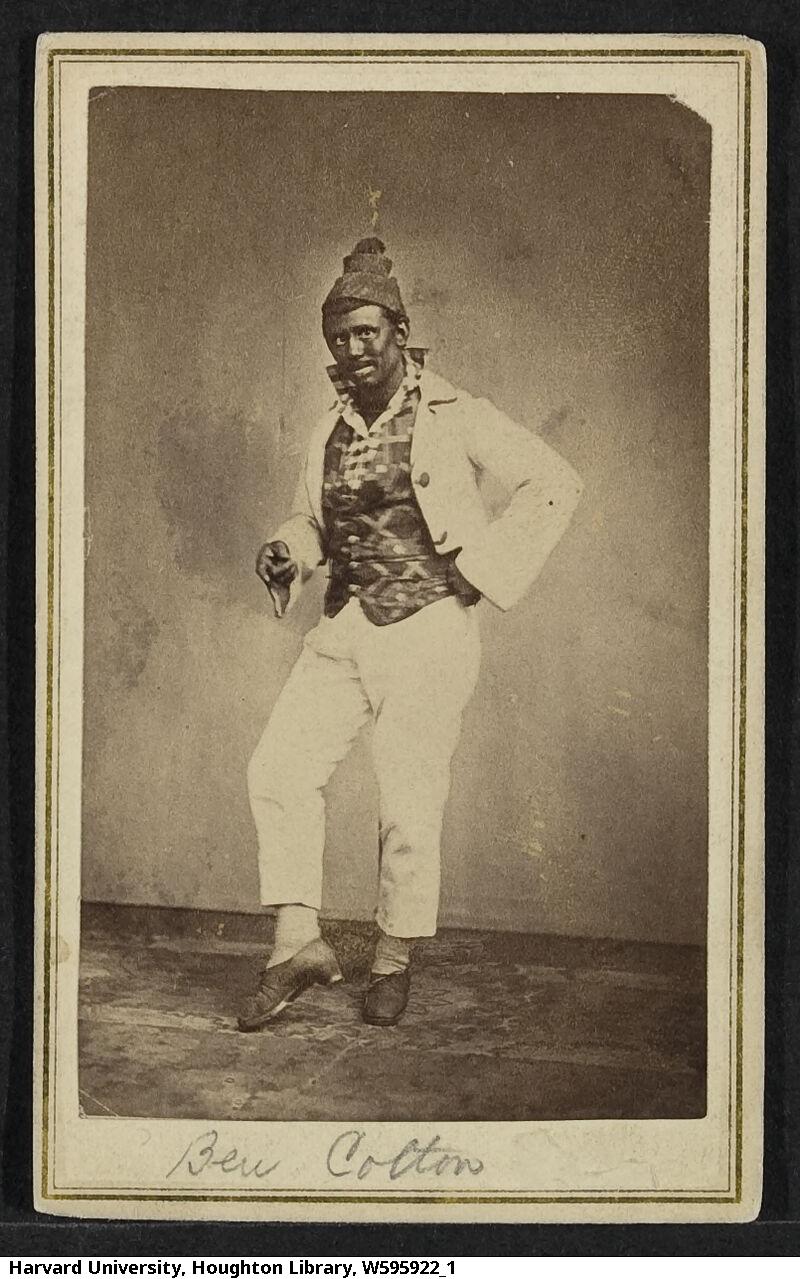

The corner space was the largest of the stores. It was occupied by Daniel Corbett’s funeral home. Perhaps the most colorful funeral held here was that of Ben Cotton on February 16, 1908. The Sun began an article saying, “They put one more of the real old time negro minstrels under the sod yesterday when they buried old Ben Cotton from Daniel Corbett’s undertaking shop at 2 Manhattan avenue.” Cotton was born in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, in 1827, where, according to The Sun, he “was a pretty well-known character.” As a youngster, he appeared in variety shows billed as Master Ben Cotton. The Sun recalled, “He drifted into minstrelsy soon after the civil war when the blackface singers and jokers were just getting ready to sweep the country, and a good part of England, by storm.” In the late 1870s, Cotton was “nearly at the head of his profession,” according to veteran vaudeville entertainer Arthur Moreland. Cotton continued his stage career until retiring in 1906 at the age of 79.

Perhaps the most colorful funeral held here was that of Ben Cotton on February 16, 1908.

Since the first years of the nation, well-to-do American women had looked to Paris for fashion trends. In 1911, however, the “Harem Skirts” were not an overwhelming hit here. On February 27, two young socialites appeared on Fifth Avenue wearing the unorthodox garment—floppy trousers that appeared when the wearer stood still to be a skirt. The New York Herald titled an article, “New York Street Throng Refuses to Grow Excited Over Fashion Freak That Caused a Riot in Paris.” The article said, “Two good looking young women wore the loose trouserettes of the seraglio…in a promenade through New York’s best known thoroughfares and into a popular restaurant.”

The journalist interviewed several women regarding their reactions, including Edith Hordlaw, who lived in the Sharon. She told him, “They’re all right and they looked real nice, but believe me these tailors have been making pants for men too long. They aren’t on to the right architecture for ladies’ trousers.”

In the pre-Depression years, residents still maintained one or two servants. On April 20, 1920, for instance, an advertisement in The Sun read: “Houseworker and nurse, two girls; $60 – $70 a month.” The wages for the two positions would translate to about $912 and $1,060 today.

At some point in the second part of the 20th century, the cornice was removed, leaving the building with a decidedly unfinished look. Otherwise, besides the carnage to the storefronts, Pelham’s 1904 design is greatly intact.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com