The Gliffden

by Tom Miller

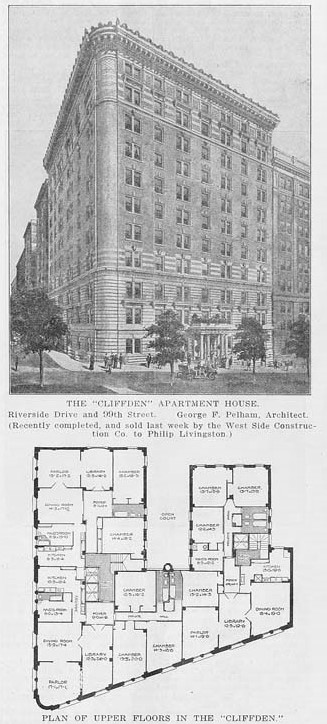

In 1909 architect George F. Pelham designed an 11-story apartment building for the West Side Construction Co. to be located at the southeast corner of Riverside Drive and 99th Street. Known originally as The Gliffden, it was completed before the year’s end. Pelham’s tripartite Renaissance Revival design included a three-story rusticated limestone base with a handsome entrance portico supported by fluted Doric columns. The six-story midsection was defined by decorative stone band courses. Pelham gave the two-story top section a striped effect by alternating rows of brick and stone, and a substantial cornice crowned the design.

On January 1, 1910, the Real Estate Record & Guide pointed out, “The marble-wainscoted foyer hall is a very handsome feature of this well-built house.” There were two apartments on the ground floor and three each on the upper floors, ranging from seven to nine rooms. An advertisement boasted, “Largest rooms on Riverside Drive. Every convenience known. Absolutely fireproof. Arrangement of rooms unsurpassed.”

Unfortunately for the well-heeled residents, the building’s unusual name caused confusion, with newspapers routinely calling it the Gliffden, the Glifden or the Clifton, for instance. Equally confusing was the address, listed as either 264 or 265 Riverside Drive. (Perhaps bowing to usage, by 1915, the building was advertised as “The Clifden.”)

The Gliffden filled with affluent residents, like banker Alexander Walker and his wife, who were among the earliest. On the weekend of July 5, 1912, Walker drove to Rye, New York in search of a summer home. Instead of his wife, he took with him another banker, Walter Butler. Walker may have rethought his decision to drive himself following a terrifying accident on the way home on Sunday, July 7.

The tenant sued the building, alleging negligence in not thoroughly vetting the employee.

As he approached Jerome Avenue and 184th Street, Walker drove up on a dirt wagon driven by Frank Hammond. Thinking he had enough room to pass, he did not attempt to slow down. The New York Times reported, “The car sheared off the left rear wheel of the wagon and shoved it forward fifteen feet before Walker could apply the brake.” Walker was “jammed between the seat and the steering gear of his car,” according to the article, while Butler and Hammond were both thrown to the roadway. Hammond had barely landed when he was buried by his entire load of sand. When he finally extricated himself and got the sand out of his eyes, he found Butler unconscious on the roadway and Walker “crying loudly in pain,” pinned inside the wreckage.

A policeman and an electrical contractor worked to free Walker from the car, and then Butler and Walker were then taken to a physician’s home nearby. The New York Times reported, “Mrs. Walker, in response to a telephone message, motored up to the surgeon’s office and took her husband home.” Butler was sent back to New York City in a taxi. Both the automobile and the wagon were totally wrecked.

In 1915 a 7-room apartment with two baths was listed at $1,500 a year—or about $3,600 per month by 2023 conversion.

Towards the end of 1916, an assistant porter and general mechanic was hired after giving “certain telephone references,” as noted by The New York Times. After having worked for two or three weeks, he appeared at the door of an apartment, saying he needed to fix a radiator that was leaking into the apartment directly below. “After working for a few minutes on the radiator in one of the bedrooms he left, stating that he was going out after some more tools.” He did not return, nor did the $2,000 in jewelry that was found missing from a bureau drawer.

The tenant sued the building, alleging negligence in not thoroughly vetting the employee. But the fact that every apartment was supplied with a wall safe proved the undoing of the tenant’s complaint. After three decisions in favor of the landlord and three appeals, the tenant gave up in September 1919. The courts ruled that, for one thing, the tenant was as negligent as the landlord by “not placing the jewels in a wall safe provided by the landlord.” The case set a precedent in landlord-tenant cases.

The well-heeled occupants were highly inconvenienced in 1936 when building workers walked off the job in demand of better wages and conditions. The New York Post noted on March 2, “Wages that range as low as $15 a week and working hours as high as eighty and ninety a week are among the grievances that motivate today’s strike of Manhattan building service employees.”

A reporter checked in at the Clifden and spoke to “a gray-haired woman tenant.” She had two opinions of the strike. Saying first, “I think someone ought to go to jail for this!” she told the journalist her husband had a weak heart, and walking the stairs could prove fatal. On the other hand, she admitted, “I don’t know, though. The boys surely don’t get a lot.”

A highly respected resident was Dr. Peter Houston Milliken who lived here with his wife, the former Adelaide Louise Thomson by the 1930s. The Presbyterian clergyman had graduated from Rutgers University in 1876 where he played football. After serving several pastorships, he was assistant pastor of the Marble Collegiate Church at the corner of Fifth Avenue and West 29th Street from 1911 to 1917. In 1921 he became the chaplain of the Presbyterian Home for Aged Women until his retirement in 1939. Milliken was ill when he retired, and he died in his apartment at the age of 90 on October 1, 1940.

The building was remodeled again in 1942. Once touted as having the “largest rooms on Riverside Drive,” there were now seven apartments per floor ranging from 3-1/2 to 4-1/2 rooms each. An advertisement on September 18 called it “completely rebuilt for modern living,” and boasted, “Venetian blinds, recessed radiators, Music by Muzak and other up-to-the-minute features.”

Among the new residents was composer Alex North, best known for his many film scores, including A Streetcar Named Desire, Cleopatra, Spartacus, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and Viva Zapata! He was nominated for 15 Academy Awards, although he never won. His 1955 Unchained Melody was written for the prison film Unchained. It became one of the most recorded songs of the 20th century.

The Brooklyn Eagle said, “their victim was not a policeman and didn’t have a gun.”

In her 2003 biography Alex North, Film Composer, Sanya Shoilevka Henderson writes that in his Riverside Drive apartment “were always musicians, artists, people that would come and stay around until odd hours of the night, as well as thorough the night. They worked on show tunes, or sang and amused themselves.” North would die on September 8, 1991 in California and his ashes were scattered at sea.

In July 1954 “two young thugs,” as described by the Brooklyn Eagle, brutally murdered fisherman Howard Englander on Manhattan Beach to obtain his money and car. Later 23-year-old Richard Connors and Ernest Lee Edwards, who was 24, were driving his car on the Upper West Side of Manhattan when they spotted Murray Lichtenstein, a resident of the Clifden, walking along West 99th Street between West End Avenue and Riverside Drive. According to Connors, Edwards thought he looked like a cop. They attacked him with an iron pipe to get his gun “for more holdups.”

Lichtenstein’s cries for help attracted police, who apprehended the pair. The Brooklyn Eagle said, “their victim was not a policeman and didn’t have a gun,” but the responding police did. Lichenstein was scheduled to testify against the pair in their January 1955 murder trial. But four days before the proceedings began, the 42-year-old Lichtenstein was found drugged and near death in a Newark hotel. Despite the suspicious circumstances, Assistant District Attorney Joseph Hoey said “he could find no connection between the scheduled trial and Lichenstein’s actions.”

The Clifden got its cinematic debut in 1975 when director and producer Woody Allen used one of the apartments in his film Manhattan.

The building became a cooperative in 1992. After its early decades of confusing name changes, it is known today as the Riverview. Sadly, at some point, George F. Pelham’s handsome cornice was removed and no effort has been made to replace it.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com