28-46 Manhattan Ave.

by Tom Miller

In 1895, architect Charles Stegmayer designed a row of apartment houses that would fill the eastern Manhattan Avenue blockfront of 101st to 102nd Streets for developer Jacob Jung. Completed the following year, the interior buildings were nearly identical. Five stories tall above basements, their arched entrances within elaborately carved Renaissance-style frames sat atop stone stoops. Above the rusticated limestone bases, the upper floors were clad in tan Roman brick and trimmed in stone. Individual cast metal cornices crowned the designs.

An advertisement touted, “Elegant apartments, 6 and 7 large, light rooms and bath; oak woodwork, hot water supply, steam heat, open nickel plumbing; every modern improvement, rents $30 to $36.” The monthly rent for the most expensive apartments would translate to about $1,400 in 2025.

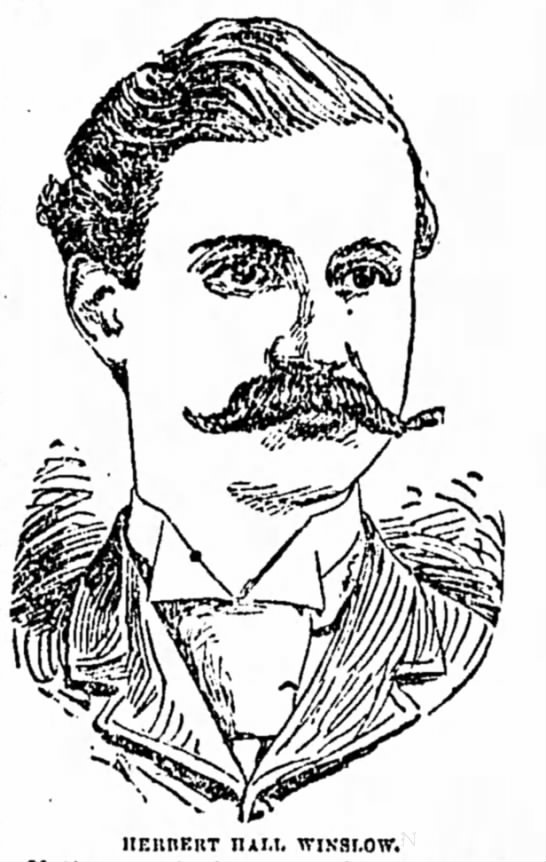

Among the early tenants of 44 Manhattan Avenue was Frank L. MacSorley, the head of MacSorley Co., listed as “supplies for engineers, plumbers and factories, steam heating apparatuses, engineers and steam fitters.” The Winslow family was also an initial resident. Dr. Charles H. Winslow was a retired chemist (or pharmacist). When the family moved into the building, Arthur S. Winslow had taken over his father’s pharmacy. The elder Winslow was born in Claremont, Massachusetts, in 1832. His other son, Herbert Hall Winslow, was a playwright; his first play to appear on Broadway was in 1890.

By the first years of the 20th century, Herbert H. Winslow had acquired a home in New Rochelle, New York. He had written several plays by then and scores of vaudeville sketches. In April 1904, Charles W. Winslow was “stricken with paralysis,” according to The New York Times, suggesting that he suffered a stroke. He was taken to Herbert’s New Rochelle home to convalesce, but died there two weeks later, on April 30.

Tragically, it would not be the only death that night.

The first occupants of 46 Manhattan Avenue represented a mixed lot—among them were Ann Norris, an actress; barber Philip Schneider; Park Sulligan, who was an electrician; attorney Alfred Hector; and William L. Trafford, a clerk in the Criminal Courts Building.

Gertrude White and Edna Grattan shared an apartment at 46 Manhattan Avenue in 1909. Gertrude, who was 20, “came from a prominent family in Beverly, Massachusetts,” according to Edna, “but had been on the outs with them.” Also living in the building was William Wasson, who owned a motorcar. On Friday night, August 27, he invited the women to an automobile race at Brighton Beach. While there, they witnessed a tragedy. The Sun reported, “They sat in the grandstand, not 200 yards from the place where [Louis] Cole was killed.” Tragically, it would not be the only death that night.

Following the race, the trio had a late supper and returned to 46 Manhattan Avenue around 1:00 in the morning. The New-York Tribune reported, “Half an hour afterward Miss White was heard screaming.” According to The Sun, Gertrude “lost her balance and fell down the airshaft to the pavement.” The janitor, hearing her scream, discovered her unconscious body. She died in the J. Hood Wright Hospital two hours later without ever regaining consciousness. The New-York Tribune rather callously titled the article, “Merrymaker Falls To Death.”

The William K. Spengler family occupied an apartment at 44 Manhattan Avenue in 1911. According to Spengler, his son Charles worked in “the office of a large corporation,” earning $70 per week. (The salary would equal about $126,000 per year today.) Despite his ample income and living with his family, Charles started a side-line by taking a quick private detective course. As soon as he got his “brand-new nickel badge and a card from a private detective agency,” as related by The New York Times, he then placed an advertisement for his services.

On the night of May 22, 1911, his first client knocked on the Spenglers’ door. The man explained he needed a detective “in a divorce case.” Charles told him that “divorce detection was his specialty, and that $5 a day was his charge.” The client asked to see his identification, and then identified himself as State Detective Frank Whitfield. He arrested Charles Spengler for “posing as a private detective without a license.” In court, Spengler insisted he truly believed he was a qualified private detective and had no idea that the agency was phony. Although the magistrate believed his story, he held Charles on $50 cash bail, which William furnished.

Among the Spenglers’ neighbors in the building were John Dunn and his wife. On the night of August 16, 1912, Mrs. Dunn answered the door to find two policemen in the hall. The Evening World reported that she “screamed” at them, “What do you want here?”

Officers Mazer and Duffy replied, “Your house is on fire, madam.”

Mrs. Dunn said, “You are mistaken,” and started to close the door. The cops “pushed their way into the apartment and found the lace curtains in the parlor blazing,” said The Evening World. They extinguished the flames before the firefighters arrived. Mrs. Dunn changed her tone. “Then Mrs. Dunn thanked them,” said the article.

David Gibbs arrived from Scotland in 1902 and found a job as a carpenter. By the end of 1913, he had saved enough money to rent an apartment at 44 Manhattan Avenue and send for his wife, Margaret, and their five grown children. By the spring of 1914, all the children had found work. Unfortunately, in the Gibbs’s case, absence had not made David Gibbs’s heart fonder.

At around 9:15 on the morning of March 26, 1914, after the Gibbs children had left for work, another tenant on the floor, Emma E. Lichhult, “heard high words,” as worded by The New York Times. She later told a reporter that Gibbs “had been out of work a long while and had been drinking heavily, and quarrels were frequent.” Emma Lichhult crept into the hallway and listened at the door. She heard Margaret fall to the floor. Inside, David Gibbs had slashed his wife’s throat with a straight razor. A second later, David Gibbs flung open the door, “lifted Mrs. Gibbs’s body from the floor, and hurled the body at her [i.e., Emma Lichhult] while grinning and holding the razor in his hand.”

Mrs. Dunn said, “You are mistaken”

Emma Lichhult ran for help. By the time police arrived, Gibbs had attempted to cut his own throat. He was charged with “felonious assault and attempted suicide,” according to The New York Times. He confessed to the murder at the police station, “and said he hoped he would be given quick passage to the electric chair,” recounted The Times.

Leo Walker, who lived next door at 46 Manhattan Avenue in 1917, worked as a summer chauffeur “for residents of Rockaway,” according to The Sun. That year the 30-year-old and another seasonal chauffeur, Thomas Burns, met 19-year-old Mildred Mott. She was the “daughter of respectable parents” in the Rockaways, according to The Sun. The three engaged in what police called “a gang of marauders who have been carting away in an automobile the contents of some of the summer homes in the Far Rockaway section.” Walker and his cohorts were arrested on March 28 while burglarizing the home of Mrs. Isaac Finger.

Grace B. Horton, a widow, lived in the apartment of her son, Albert, and his wife at 44 Manhattan Avenue in 1919. That summer, she visited an eye specialist, “who told her that her sight was going,” as reported by The Evening World. The newspaper said that since the diagnosis, she had “been melancholy.” On the night of September 3, Grace complained to her son and daughter-in-law “that she had been unable to read a line in the paper with a microscope and that there were worse things than death.” The next day, The Evening World reported, “When her son opened her door this morning she was dead in bed with the end of a rubber tube in her mouth with the other fastened to a gas jet.”

At some point after the mid-century, the cornices were removed, and the stoops were converted into flower beds. The entrances were consolidated at the corner, at 48 Manhattan Avenue.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com