Erco Hall, 328 West 86th Street

by Tom Miller

In the first half of the 19th century, the Somerville estate engulfed the district around what would become Riverside Drive and 86th Street. As the city expanded northward, the estate was eventually engulfed by upscale rowhouses and mansions. The Somerville family lived at 328 West 86th Street, in “what is known as the old Somerville mansion,” as worded by the New York Herald on April 24, 1905. Living here at the time were Etta Somerville, her widowed mother, Etta’s sister Margaret, her husband Eugene Clifford Potter, and their two sons.

When the family sold the property to the Erco Realty Corp in 1924, the New-York Sun mentioned that it “was in the Potter [sic] family for a hundred years.” The firm hired the architectural firm of Blum & Blum to design an apartment house on the site. Brothers George and Edward Blum studied at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris before opening their architectural office, Blum & Blum, in New York in 1909. Their grasp of architectural trends would impact apartment designs in New York.

Although Blum & Blum made their mark with Art Nouveau and Art Deco residential buildings, they turned to the more sedate Colonial Revival style for 328 West 86th Street. Faced in Flemish-bond brick (appropriate for the Colonial period), the 15-story structure dwarfed the private homes on either side. The architects reserved the majority of the ornamentation for the three-story top section, where full-relief faces stare down from the tympana of double-height terra cotta arches.

As the building rose, on July 3, 1924 The Sun commented, “It will be the first small suite, full housekeeping apartment building to be erected on the street between West End Avenue and Riverside Drive…It will be known as Erco Hall.” There were 46 three- and four-bedroom suites with full kitchens. Rents ranged from $2,000 to $2,400, according to an advertisement in June 1925. Rent for the most expensive suites would translate to about $3,475 per month in 2024.

The financially comfortable residents maintained a small domestic staff. On September 6, 1925 (four months after Abraham Levenstein and his wife announced the engagement of their daughter Mildred to Jac M. Simon), the couple placed an advertisement in The New York Times: “Girl to do general housework and plain cooking, small family. Call between 11 and 12. Mrs. Levinstein, 328 West 86th, Apt. 9C.”

The same year, in June, the occupants of Apartment 2B advertised for help. Decades before equal opportunity laws forbade racial distinctions in ads, theirs read, “Houseworker—Refined young white woman; small apartment; assist with child 3 years old; sleep out.” The term “sleep out” meant that the servant would not be living with the family.

[Dr. Barnet] Stivelman was chief of the Pulmonary Clinic of Beth Israel Hospital and an assistant attending physician at Willard Parker Hospital [and] outspoken in exposing tacit antisemitism within the medical community.

Other early residents were Kisz Elson, president of the Elson Lumber Company, who signed a lease “for a term of years” in September 1926, and Dr. Barnet Stivelman. Stivelman was chief of the Pulmonary Clinic of Beth Israel Hospital and an assistant attending physician at Willard Parker Hospital. He was outspoken in exposing tacit antisemitism within the medical community. In a speech given at the Jewish Consumptives Relief Society convention at the Hotel Breakers in Atlantic City, for instance, he complained that there was “a woeful and neglectful” lack of hospital facilities for “Jewish consumptives in New York City and through the East.” (“Consumption” was the common term for tuberculosis.)

In September 1926, entertainers Willie Howard and his wife Emily Miles signed a lease. Howard was currently appearing in the immensely popular George White’s Scandals on Broadway. Born on April 13, 1886, in Neustadt, Germany, he would move on to motion pictures, starring in the 1937 The Smart Way and Playboy Number One and the 1941 How to Go to a French Restaurant.

Emily Miles was born in Dayton, Ohio, in 1892. Although she appeared in the 1929 movie The Music Makers, following her marriage to Howard, she essentially gave up her acting career.

Living here in 1926 was 39-year-old John Keiley. On the evening of August 26, he took his motorcycle for a joy ride to Queens. It did not end well for him. He was traveling west on Northern Boulevard in Flushing when he smashed into the rear of Albert F. Ruebsamen’s automobile. It was only the beginning of Keiley’s troubles. The Daily Star reported, “After crashing with the automobile, the motorcycle struck a bicycle, which Edward Lynch, twenty-four…was riding west on the boulevard.”

While Ruebsamen was uninjured (although his car was), both Lynch and Kieley were thrown from their vehicles. Kieley’s left leg was broken, and Lynch suffered “contusions of the left leg and hip,” according to the article. Kieley had to be hospitalized.

Well-heeled New Yorkers routinely visited Europe, and the residents of 328 West 86th Street were no exception. On November 4, 1927, for instance, The American Hebrew reported, “Among recent sea goers on the New York bound for European shores to pass several weeks were…Mr. and Mrs. Simon Hamburger of 328 West Eighty-sixth Street.”

Among the Hamburgers’ neighbors in the building were Edward F. Rosenthal and his wife, the former Dorothy Moss. Rosenthal was vice-president and sales manager of the Porto Rican-American Tobacco Company. He resigned on January 1, 1928, but was reticent to fully retire. The trade newspaper Tobacco reported, “but Mr. Rosenthal came to the office occasionally thereafter to look after his personal effects, which had not been removed.”

On Friday, January 6, the 48-year-old was “apparently in the best of health when he called at the offices of the Porto Rican-American Tobacco Company,” according to Tobacco. But, the article continued, “Rosenthal went to his home that evening and was found dead by his family early Saturday morning.” His death was not investigated, and no cause was published.

William J. Duffy and his wife, the former Frances Welsh, were living here at the time. The son of Irish immigrants, Duffy had risen through the ranks of Tammany Hall. In 1906, when he was Deputy County Clerk, he was appointed to a position in the County Clerk’s office. He was made chief clerk to the Commissioner of Records in the Surrogates’ Court in 1911. In May 1929, while living here, he was appointed Secretary of Tammany Hall, a highly influential political position.

On September 30, 1930, the Democratic State Convention opened at Syracuse, New York, to re-nominate the incumbent governor, Franklin Delano Roosevelt. While there, Duffy collapsed. While he seemed to have recovered, The New York Evening Post reported, “The attack recurred, however, when he returned to his home at 328 West Eighty-sixth Street.”

William J. Duffy was taken to the Knickerbocker Hospital where he died “of heart disease,” according to The Evening Post, on October 8. At his bedside when he died, along with Frances and their son William Jr., was John Francis Curry, the head of Tammany Hall.

Another Irish-American resident was Thomas O’Neill, who owned a taxicab and ran a restaurant in 1930. The 32-year-old had other, nefarious means to make a living during the Depression years, however. He was arrested on September 7 that year by Westchester County Park Policeman Captain R. N. Van Venmarck. The Newburgh News reported that Vanmarck, “charges that O’Neill was one of the four men who held-up the office of Playland Park, Rye, on Labor Day morning and escaped with $12,000, including 30,000 nickels.”

O’Neill and his cronies had “cowed the cashier of Playland Park with sawed-off shotguns and escaped in an automobile,” said the article. Thomas O’Neill countered that he was with his wife and family “on an Albany night boat” at the time. O’Neill’s criminal record, however, did not help his case. He had been arrested five times since 1916 for “robbery, burglary, felonious assault and grand larceny.”

Pearl Bernstein reflected more positively on the address. She and her husband, Dr. Louis William Max, a professor of psychology at New York University, were married in 1929. Pearl had graduated from Barnard College in 1925 and immediately threw herself into local government. She told The New York Sun on December 28, 1933, “After I got out of school I worked for three months for the Citizen’s Union during the [James] Walker campaign, then served as a volunteer on the league’s municipal affairs committee and eventually became a staff member.”

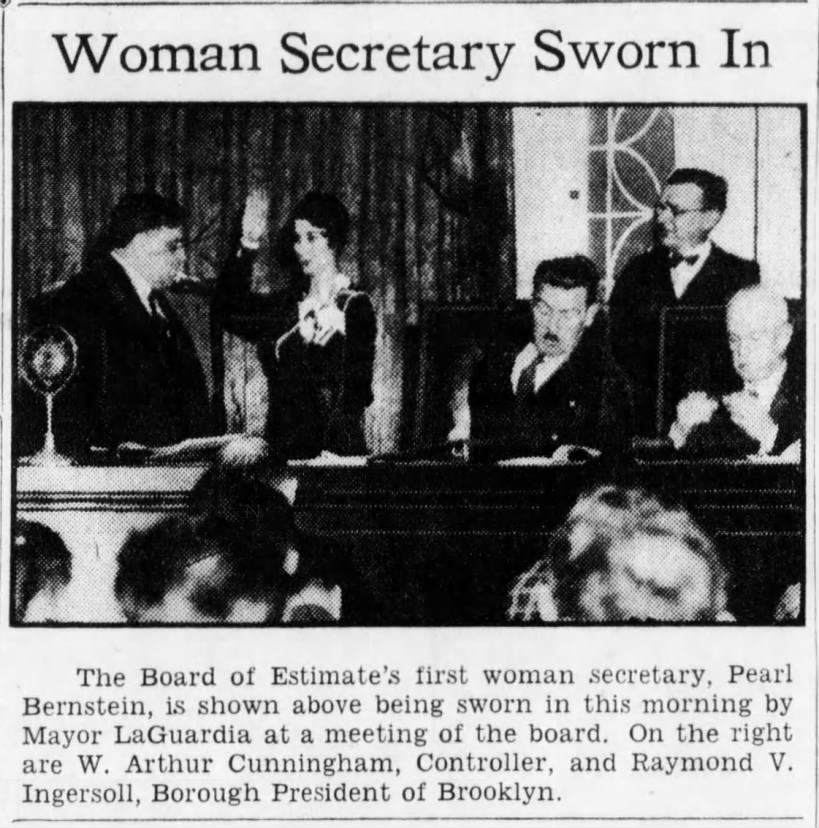

When the new mayor, Fiorello LaGuardia, was installed, he appointed Bernstein Secretary of the Board of Estimate.

Politics in the 1920s did not include women. But Pearl Bernstein was not afraid of knocking on glass ceilings. When City Hall continued to say there was “no money” for the issues for which the Citizen’s Union lobbied, Pearl marched into the Board of Estimate meetings and took a seat. At one meeting, when there were not enough copies of the proposed new budget to go around, Bernstein refused to allow the meeting to continue until she had a copy. “I told Mayor O’Brien that it was impossible to comment intelligently on the budget unless I had a copy, and I insisted until I got it,” she told The New York Sun reporter.

Pearl Bernstein’s persistence and aptitude paid off. When the new mayor, Fiorello LaGuardia, was installed, he appointed Bernstein Secretary of the Board of Estimate. The Sun reported it was “the first time that a woman ever has held that important $10,840 post.” (Pearl Bernstein’s salary would equal $198,000 today.)

Even during the Great Depression, some residents could afford to travel in high style. On September 14, 1934, for instance, The American Hebrew and Jewish Tribune reported, “Nathan Cohen and his sister, Miss Fanny Cohen, of 328 West Eighty-sixth Street, New York, who have been in Europe this past summer are at the Grosvenor House, Park Lane, London, for the holidays. They are worshipping at the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue there.”

Joseph Schlesinger and his wife, Mollie, were residents by the 1940s. Born in 1890, since 1928, he had been the head of the Ideal Uniform Cap Company, founded by his father. The couple had an adult son, Sol, who lived in Nassau County. Joseph Schlesinger retired in 1945, and died on November 27, 1949 at the age of 60.

The Daniel Kondakjian family, who lived here by 1960, maintained two other homes, one in Belmar, Long Island, and another in New Jersey. Their daughter, Virginia, attended the prestigious Prospect Hill Country Day School and received her Bachelor of Music degree from Westminster Choir College in Princeton, New Jersey. She went on to study voice in Milan, Italy, and at the Opera Academy in Vienna, Austria. Virginia’s parents announced her engagement to Diran M. Kaloostian “at a reception in their Belmar home,” according to The Coast Advertiser, on October 19, 1960.

A fascinating resident was Moses J. C. Kornblum, who lived here with his wife, the former Myrille Soloman. Long before Kornblum made his living as the Eastern sales manager of the Cleveland-based Tasa Coal Company, he was a sportswriter.

In 1907, he wrote an article about a University of Pittsburgh football game for the Pittsburgh Leader. In it, he voiced his frustration at the near impossibility of keeping track of individual players. The problem could be rectified, he opined, by putting numbers on their uniforms. The very next year, according to Allison Danzig in The History of American Football, the University of Pittsburgh players had numbered jerseys in a game against Washington and Jefferson College.

Moses Kornblum underwent surgery at Mount Sinai Hospital in September 1964. He and died there at the age of 79 from complications.

A century after the first residents moved into the building and began advertising for cooks and housekeepers, little has outwardly changed to Blum & Blum’s prim Colonial Revival building. And whether anyone ever truly referred to it as Erco Hall is doubtful.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com