471 West End Avenue

by Tom Miller

In 1885 builder George W. Rogers commissioned the architectural firm of McKim, Mead & White to design six houses that would wrap the southwest corner of West End Avenue and 83rd Street. West End Avenue was developing as an exclusive residential thoroughfare lined with grand mansions. Completed in 1886, four of the homes faced 83rd Street and two, including the showstopper at the corner, faced West End Avenue. That house was separated from what seems to have been the step-sister of the group by a walled garden. Without the Flemish gables, turrets and balconies that distinguished the others, 471 West End Avenue was, at best, the least showiest.

In 1887 Rogers sold the houses to real estate operator Edmund Dodge, who resold 471 West End Avenue to Cora A. Slocomb for $32,000, or about $898,000 by today’s conversion. Slocomb, who lived in New Orleans, Louisiana, purchased the house as an investment property.

Perhaps her first tenants were author and historian John Clark Ridpath and his wife, who lived here by the mid-1890’s. Born in 1840, he had taught at De Pauw University until resigning to devote himself entirely to writing. His 1882 History of the World, which filled four octavo volumes, sold more than 150,000 copies. While living here he was editor of The Arena magazine, and completed his Life and Times of Gladstone and a supplement to the History of All Nations.

Ridpath was taken to the Presbyterian Hospital on April 26, 1900 with typhoid fever. His condition worsened when he contracted pneumonia, and he died on September 30 at the age of 60.

By now Cora Slocomb had married Count Detalmo di Brazza Savorgnan. While Ridpath was still in the hospital, on September 1, 1900, The Sun reported that “Countess di Brazza-Savorgnan of Friuli, Italy,” had sold the 23-foot-wide house to Charles E. Willcox.

The house saw a quick succession of owners until 1906 when it was purchased by wealthy real estate operator Henry Hellman and his wife, Marguerite Dacy. The Hellmans owned the Junction Realty Co. They leased the house to Walter C. Adams in August 1906 for three years. It was the start of a very colorful chapter in the history of 471 West End Avenue.

Walter Adams was the youngest son of “Policy King” Albert J. Adams. Known nationwide as “Al” Adams, the New York Herald called him “the millionaire policy sharp, the released convict [and] more recently backer of bucket shops.” (Policy games were illegal lotteries, later known as the numbers game; and bucket shops were establishments operating under the pretense of a brokerage firms; but which in reality took “bets, or wagers…on the rise or fall of the prices of stocks,” as defined by the Supreme Court.)

Adams’s wife, Isabella V. Adams moved into the West End Avenue house with Walter, another son, Louis B., daughter Ida, and Isabella’s half-sister, Celia M. Thatcher. (Two other sons, Albert Jr. and Lawrence P. were both married and lived elsewhere.)

A very troubled Al Adams had chosen to live apart from his family, and moved onto the 15th Floor of the Ansonia Hotel. The New York Herald explained, “Adams had convinced himself that the future which he had dedicated to his family would be best conserved if he dropped out of it.”2).

While living here he was editor of The Arena magazine, and completed his Life and Times of Gladstone and a supplement to the History of All Nations.

On August 29, 1906, one week after Isabella and her two children moved into 471 West End Avenue, Al Adams shot himself in his Ansonia suite. The New York Herald estimated his personal fortune at $8 million–closer to $227 million in today’s money. His funeral was held in “the fine residence at 471 West End Avenue,” as described by the New York Herald. The article noted, “A burglar proof case was provided for the interment of the body in Woodlawn cemetery.” It was a precaution against the stealing of corpses of the wealthy and holding them for ransom.

Other than small bequests to friends and family, like Celia Thatcher, Isabella received one-third of the massive estate, the rest being divided among her children. It seemed like a routine probate of the will. But an astonishing twist arose two years later.

In May 1908, Thomas Bertiero sued Isabella for his help in convincing Al Adams to treat her so liberally in his will. Saying that Bertiero “is on terms of intimacy with the inhabitants of the spirit world,” The Evening World explained that he “sets up the extraordinary claim that he set a trained troupe of spirits upon Adams and that the said troupe of spirits influenced the policy king to leave his wife $2,000,000.”

According to him, Isabella was concerned that she would be cut out of her husband’s will. Bertiero’s lawyer explained that “some time before Al Adams committed suicide…Mrs. Adams summoned Bertiero to her home.” There, he continued, “she asked Bertiero to place Al Adams under spirit influence and soften his heart toward her.” His client now sought payment for “psychological and special services.”

The attorney was having problems serving a summons on Isabella. The Evening World she “left the city with her son and unmarried daughter just before Easter and has not communicated with her servants.” In the end, it made little difference, as Bertiero lost his case.

Trouble of a much different sort occurred on January 27, 1909. Isabella was ill, and her lady’s maid, Sylvia Thorne, called down the dumbwaiter and asked the cook, Eliza Devereaux, to send up a pot of tea. A few minutes after the tea arrived, Sylvia called for “some toast–three slices.” The Evening World reported, “In a minute the toast came down again and Sylvia Thorne ordered that it be buttered.”

Cooks were the most highly-paid servants in a household and they maintained an air of self-importance. The newspaper said, “Doubtless it is an insult to ask a cook to butter toast. Mrs. Devereaux said she had been cooking for the best families for twenty-five years and had never been so ordered before. She refused to butter the toast.”

Quite annoyed, Sylvia Thorne descended to the kitchen and buttered the toast herself. “While so doing she expressed her opinion of Mrs. Devereaux quite freely, whereupon Mrs. Devereaux picked up a panful of spinach and spilled it over her head.” It triggered a heated food fight between cook and maid.

Sylvia picked up a pound of butter, “frozen hard from the ice box.” She hurled it at Eliza Devereaux (described by the article as “aged forty-five, well equipped as to flesh and rubicund of countenance as a cook should be), hitting her in the throat. Eliza picked up “that favorite weapon of cooks–a rolling pin. With this she drove Sylvia Thorne from the lower regions of the mansion.”

Having vanquished her foe, Eliza Devereaux “gave her notice and left.” She went directly to the police station and filed a complaint of assault. In court, Magistrate Breen dismissed the charges, deciding that Sylvia Thorne “had been sufficiently aggrieved by a shampoo of spinach to warrant her in propelling the butter at Mrs. Deveraux.”

The Adamses’ lease on the house expired that year and the family left. In December 1909, the Hellmans upgraded the house by having electricity installed by the Power Engineering & Contracting Co. Rather than continue to rent it, they moved in. The couple improved the house again in 1912 by hiring architects Comyns & Todaro to add a one-story addition to the rear.

The Hellmans were at their country house in the summer of 1913, but Marguerite came home for a few days to check on “some renovating,” as worded by The Sun. She was out on the afternoon of July 23, 1913 when a workman appeared at the door. The Syracuse Herald reported, “The negro butler admitted a man who said he had been sent to finish some plastering and painting in the bathroom. The stranger spent a little time puttering about with some tools in the bathroom and then left the house, saying that he had to get more material for his work.” He never returned.

When Marguerite came home, she found her trunks had been opened and jewelry and cash stolen. Police reported the burglar had gotten away with $5,000 in valuables and money, but had “missed $40,000 worth of jewelry in a pasteboard box in the tray of the trunk.”

Around 1916, the Hellmans sold the house to Elizabeth S. Rothschild, the widow of Martin Rothschild. She made significant renovations by adding a fourth floor in the form of a slate-shingled mansard with a large, centered dormer; and removing the stoop and lowering the entrance to below sidewalk level. The New York Herald reported, “the two top floors have been converted into a large studio,” adding, “the house contains an electric elevator.”

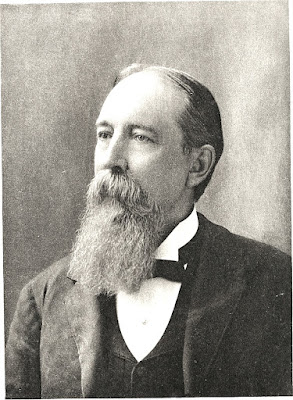

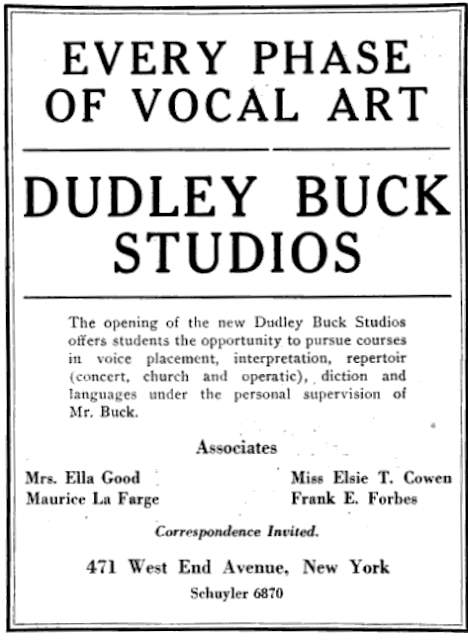

Rothschild sold the house to vocal instructor Dudley Buck in 1922 for $75,000–around $1.16 million today. In its October issue that year, The Musical Observer wrote, “Dudley Buck, the well-known New York singing teacher, has moved into new quarters, principally owing to the fact that his former studios proved inadequate to the growing demands of his classes.” The article explained that now “his assistants could have studios under the same roof with him and…he could provide the necessary personal touch to every student whether studying with him directly or not.”

Buck offered rooms not only to his associates. An advertisement in the New York Herald in September 1922 offered, “Luxurious bachelor quarters in private house equipped with automatic elevator; one or two rooms, private bath, handsomely furnished.”

Buck was almost assuredly approached in 1923 by the developers who demolished the rest of the McKim, Mead & White grouping. But for some reason, he held out. Because of the garden between 471 West End Avenue and the corner house, the razing of the house next door had no structural effects.

Buck was almost assuredly approached in 1923 by the developers who demolished the rest of the McKim, Mead & White grouping. But for some reason, he held out.

Among his Dudley’s tenants in 1923 was rare book collector and dealer Gabriel Wells. He had come to America from his native Hungary in 1894, “penniless and ignorant of English,” according to the Watertown Daily Standard. By the time he moved into 471 West End Avenue he had come a long way. He was in Paris in the summer of 1925 when he heard of the impending demolition of the house in which Balzac had lived and worked from 1842 to 1848. It had been maintained as a house museum, the Muse Balzac, by the Societe Honore de Balzac. But the society had run out of funds. The Watertown Daily Standard reported that Wells “learned of the danger to the house and subscribed 50,000 francs to buy the building, at the same time informing the society that it could draw upon him for a larger sum if necessary.”

Dudley Buck sold the house in November 1929 to Harold A. Foster, who resold it seven years later to the Esjol Realty Corporation. The New York Times reported, “changes planned by the new owner include the construction of a physician’s apartment with private street entrance. The house will have one and two room apartments with kitchenettes, new baths and a three-room suite with roof terrace.”

Tenants throughout the succeeding decades continued to be middle- and upper-middle class, like David E. Glasser, a graduate of Columbia University’s School of Architecture, who lived here in 1961.

A few years later, 471 West End Avenue was home to the Agudas Israel World Organization. On January 8, 1967 it held an open house of its newly renovated apartments. The notice for the event was entitled “Apartments for Victims of Nazi Persecution.” Applicants could sign up for 1-1/2 and 2-1/2 room spaces.

In 1999 the house was purchased by real estate investor Rod Hickey, who initiated façade repair in 2003. On November 9, The New York Times columnist Christopher Gray remarked, “Now the building excites little curiosity from the street, and looks like any old raggle-taggle converted row house with rental apartments.” A fire in 2013 tore through the interior of the vintage residence, greatly damaging the gable. It was placed on the market in 2016 for just under $10 million.

Squeezed in between two apartment houses, the once-proud relic looks rather forlorn and out of place, today.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at https://daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com/