64 Manhattan Ave.

by Tom Miller

In 1895-96, real estate developer Nicholas Cotter filled the northern half of the east blockfront of Manhattan Avenue between 102nd to 103rd Streets with three flat (or apartment) buildings. Designed by John C. Burne, they were five stories tall and faced with tan Roman brick and trimmed in limestone. At $55,000 to construct, the corner building cost twice as much as the other two structures. Burne wandered from its overall neo-Grec design by giving the entrance at 18 West 103rd Street a Renaissance Revival framework. Exuberantly carved panels decorated the Corinthian pilasters that flanked the doorway. They upheld a stone-framed transom and an intricately carved entablature.

There were just 12 apartments in the building. Potential residents could choose between six or seven rooms with a bath.

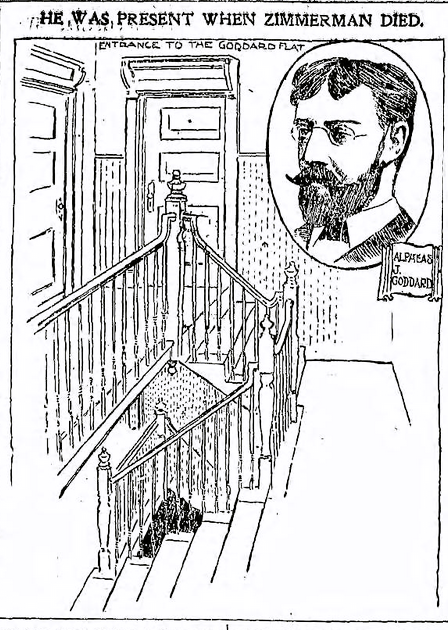

Among the initial tenants were Alpheus J. Goddard and his wife. Born in 1869 and a graduate of Amherst, Goddard was the head of the New York City office of Adamant Mfg. Co., a maker of wall plaster.

On February 13, 1899, The New York Times reported that the firm had failed. The home office in Syracuse, New York, said the article, “lays its downfall partly to the management of the former New York agent, Alpheus J. Goddard.” A reporter had visited his apartment the night before. Goddard told him that “he had severed his connection with the company last October and had nothing to say regarding the concern’s affairs at present.” According to Goddard, he had turned to real estate as his profession. (In fact, he was in a personal financial crisis and had been arrested for assaulting a collection agent.)

A month later, Alpheus J. Goddard was chosen as the foreman of the trial of Dr. Samuel J. Kennedy, accused of murdering Dolly Reynolds. It was Goddard who declared in court on March 31 that the jury found Kennedy guilty of first-degree murder. The verdict came with a death sentence. Before long, Goddard would be back in court regarding another murder case—and this time, he was the defendant.

Alpheus J. Goddard was chosen as the foreman of the trial of Dr. Samuel J. Kennedy, accused of murdering Dolly Reynolds.

German immigrant Louis Zimmermann, who ran a store at 248 West 106th Street, had been trying to collect the $40 that Goddard owed him for months. Finally, on October 28, he told his wife he was going to Goddard’s apartment to collect. When her husband did not come home that night, Mrs. Zimmerman became anxious. Unable to speak English, the elderly woman searched frantically for two weeks before going to the Legal Aid Society for help. Two weeks later, investigators discovered that Louis Zimmerman was dead and buried.

It would not be until March 1899 that facts surrounding his death began coming to light. Investigators discovered that a 12-year-old boy, John Day, had directed Zimmermann to Goddard’s building and taken him to the apartment on the third floor. According to the boy, Goddard told Zimmermann he would have his money the next week, and Zimmermann replied he had rent to pay. He remembered Goddard saying, “You get out of here or I’ll throw you down the stairs!”

As the argument became increasingly heated, Daly started to leave, telling a reporter from The New York Times, “I started downstairs, as I thought there might be trouble.” And there was. Just as the boy reached the ground floor, he heard Zimmermann crashing down the stairs. Daly turned back to find the old man at the second-floor landing. “He was all doubled up, and the blood was running from a big cut in his head,” he said. Louis Zimmermann was dead, his neck broken in the fall.

Against the protests of the building’s janitor, Goddard demanded that he take Zimmerman’s body into an empty flat. The janitor notified the police, who later instructed that the unidentified corpse remain there until the coroner gave permission to remove it. Instead, Goddard had it rushed to an undertaker and paid for the burial.

A grand jury convened on July 6, 1889. Among the witnesses was the janitor of 18 West 103rd Street. He testified that Goddard had instructed him to clean up the blood and to burn Zimmermann’s hat. “It was my impression that the hat had been put on Zimmermann’s head after he fell. It looked that way, for it was not dented,” he told the jury. When he balked at burning the hat, “I was ordered to do as I was ordered and keep my mouth shut,” he said.

Despite that and other damning evidence, the jury decided Zimmermann had died by falling downstairs “in a manner unknown to the jury.” Mrs. Zimmermann, who had cried throughout the procedure, asked Goddard for the $40. The New York Times reported, “He finally paid her $10, which he said was all he owed.”

Another initial resident was Dr. Evelyn Garrigue. Born in 1855 in Canterbury-on-Hudson, she graduated from the Medical College of the Women’s Hospital in New York in 1896. She also studied in Paris and Vienna. She was head of the infirmary of the Women’s Hospital and taught anatomy and nursing classes. She was, as well, the secretary of the Women’s Medical Association of New York City.

Nearly all residents here had a servant, and Dr. Garrigue’s was Lena Bechtel. On the afternoon of January 22, 1900, a fire broke out in the apartment. With a somewhat sexist view, The Democrat & Chronicle of Albany opined, “Courage and coolness, shown at a time when most women would have been wringing their hands and hysterically shrieking, enabled one woman to save a flat house and probably several lives.” The article said, “Lena Bechtel is German, therefore phlegmatic—that kind of woman who forgets to be excited.” The article said she “worked hard” and extinguished the fire without the aid of firefighters.

Another impressive resident was Mary Frelinghuysen Hurlburg. She graduated with a bachelor’s degree in 1887 and a master’s in 1893, both from Wellesley. Her degrees were in education and physics. She was doing graduate studies at Columbia in 1902 when she transferred to Barnard College.

The Henry McMillen family was here as early as 1904. On April 22, 1896, Henry was appointed “Deputy Supervisor and Expert” with the city. In 1904, he earned $2,500 in that position. In 1907, his daughter Florence L. McMillen received her license to teach history in city schools. The family would still be living here on June 25, 1910, when the New York Herald reported that Henry and two co-workers, including the Supervisor of the City Records, resigned. The article said their resignations followed, “charges of mismanagement.”

In the meantime, H. Morton Moore and his family were neighbors of the McMillens. Moore was a retired contractor. At 5:00 on the evening of May 15, 1904, 15-year-old Frederick (known to the family as Freddy) left home to visit Miss Georgia Miller, who lived at 144 West 111th Street. As he left, his mother reminded him to be back by 9:00.

She was head of the infirmary of the Women’s Hospital and taught anatomy and nursing classes.

When Freddy did not return home, his father reported him missing. The police of the West 100th Street station mobilized a search. Eventually, Freddie walked into the door of the apartment. The excuse for his being missing “so impressed his father,” said The Sun, “that Freddie was taken around to the West 100th Street police station. All the sleuths in the precinct were sent for and Freddy unfolded his tale. The New York Times recounted:

He said that he had been accosted by two men at One Hundred and Tenth Street and Eighth Avenue shortly after 9 o’clock and had been thrown into a carriage, his hands pinioned by leather thongs, and had been driven through the Park and thence through many streets he had never before seen, until he was finally taken to a saloon, where he was brought into the presence of a man and woman. He was left alone, he said. Working his hands partly free and securing his pocketknife, he cut the thongs and so got free.

The police assured Moore that they would capture the kidnappers. The Sun, however, doubted that was true, saying, “it is a fact that all of the sleuths said “pipe!” and went to bed soon after Freddy and his father had gone.”

Caroline B. Le Row and Elizabeth Rose, both unmarried, shared an apartment. Caroline was born on Staten Island in 1844 and had taught English at Smith and Vassar Colleges. She had lectured extensively on literature and wrote English As She is Taught, a humorous book based on errors made by her pupils on test papers. Caroline Le Row retired in 1906, and three years later, “her mind became affected,” according to The Sun. (The condition was most likely what today would be called dementia.) On the morning of March 8, 1914, Elizabeth Rose went to church. When she came home, Caroline had died of a heart attack.

Beginning in the 1920s and continuing through the Depression years, the neighborhood was heavily populated with Irish immigrants. The tenant list here was peppered with surnames like O’Brien, O’Sullivan, Gallagher, and Naughton.

The store on the avenue side was home to a tailoring and laundry business in the early 1940s. More than two decades later, the Parkway Cleaners & Tailors occupied the space. Today, it is home to a deli. Other than the expected updates like replacement windows and an industrial-looking door, little has changed outwardly to the building.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com