The Alexandrian Chambers

by Tom Miller

In its June 17, 1911 issue The Real Estate Record & Builders’ Guide described Ralph L. Crow as a “man of mark in the building industry” because of his “notable current building operations.” The head of the William L. Crow Construction Company, he was among the developers who were changing the face of Manhattan with the erection of modern commercial buildings.

At the time of the article, West 72nd Street was changing from an exclusive residential street to a commercial thoroughfare. Ralph L. Crow contributed to that change in October 1921 when he purchased the four-story brownstone at 111 West 72nd Street for the equivalent of $1.43 million in today’s money. For decades it had been home to the family of millionaire hat manufacturer Robert Dunlap. Within the month, on September 17, the New York Herald reported that Crow “will alter the two lower floors into stores and convert the upper floors into small suites suitable for doctors and dentists.”

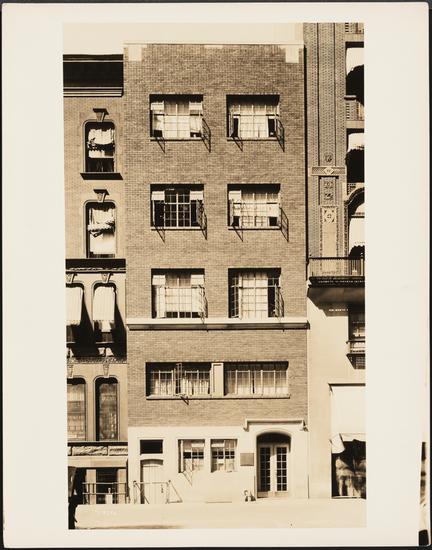

Crow hired the architectural firm of Ford, Butler & Oliver to renovate the vintage residence. They stripped off the brownstone façade, removed the stoop, and pulled the front forward to the property line. The no-nonsense design bore little ornamentation—the casement windows within the brick-faced upper floors had no lintels, and a flat-faced parapet took the place of an ornamental cornice. The limestone-clad ground floor featured an unexpected neo-Gothic, square headed drip molding above the entrance.

The New York Herald described the “elevator building designed especially for physicians and dentists” on January 22. “The new building, five stories high, will be known as the Alexandrian Chambers,” noted the article, saying it would be ready for occupancy in April.

An advertisement for offices within the Alexandrian Chambers building in June targeted “Dentists-Physicians-Oculists” and touted “unique facilities” with “especially equipped laboratories [and] ample current for x-ray work.” As Crow intended, the building filled with medical professionals, like Dr. B. C. Fairchild, a dentist, who leased office space in September that year.

Ralph L. Crow put the title to the property in the name of his wife, Ella M. Crow. The couple retained possession until January 1937 when they sold it to 38 River, Inc. At the time of the sale the building was still described as a “five-story professional building for physicians and dentists.”

On September 17, the New York Herald reported that Crow “will alter the two lower floors into stores and convert the upper floors into small suites suitable for doctors and dentists.”

But by the World War II years the tenant list was changing. In the early 1940’s Anthony’s Reducing Salon was in the building. A special in February 1943 offered new female patrons 22 reducing treatments for $10 (about $150 today). The package included “Swedish body massage, pine oil vapor baths, electric rollators, showers, charm oil, and locker service.”

By the last quarter of the 20th century there were no medical tenants left. Instead small businesses filled the offices, like the Goff Security Bureau which employed unarmed, uniformed security guards. Whether the Goff Security Bureau was aware that some of its personnel, who were not authorized to carry weapons, did so, is unclear. But the practice ended violently on January 15, 1972.

James Brown and Thomas Anderson were working as guards at Grant’s Restaurant on West 42nd Street that Friday night. Both carried concealed guns. The New York Times said the restaurant “in the Times Square area was filled with customers.” Suddenly, at 11:30 a “sharp noise” rang out and a customer lay dead on the floor.

James Brown had gotten into an argument with 32-year old Charles Pierce. When police arrived, they were initially confused, since neither Brown nor Thomas was armed. Later, investigators told reporters, “Mr. Anderson had taken the weapon and hid it in the basement of the building under several bags of food.” Brown was charged with homicide and possession of a dangerous weapon, while Anderson was charged with possession of a dangerous weapon and obstructing governmental administration.

Whether the Goff Security Bureau was aware that some of its personnel, who were not authorized to carry weapons, did so, is unclear. But the practice ended violently on January 15, 1972.

A renovation of the structure, completed in 2004, resulted in a dance studio on the first and second floors. The lower two floors were refaced in featureless stone and a show window installed. Among the subsequent commercial tenants were the Sari-Sari Store, which replaced the dance studio the following year, and Lovella Salon, in the ground floor space by 2012. Today another salon, Laveli, is in the ground floor while a fitness center operates from the second floor.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

111 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 111 West 72nd Street: