Willful Stipulations and Soul Freedom

by Tom Miller

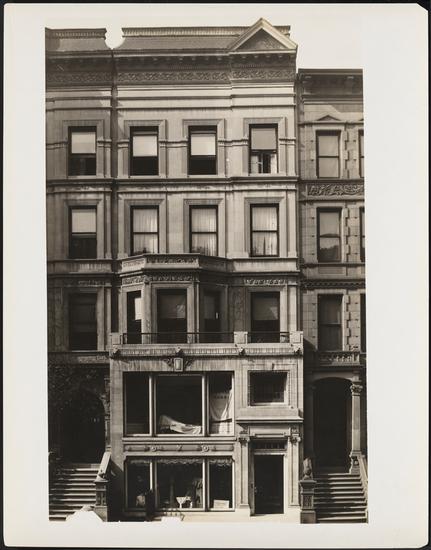

In 1889 architect Gilbert A. Schellenger designed a row of high-end homes along West 72nd Street for Francis and Margaret Crawford. At the time the street one of the most exclusive residential thoroughfares in the city. Commercial traffic was restricted, and so other than occasional and necessary delivery wagons, only the elegant carriages of the residents were seen.

The Crawfords sold the completed 25-foot-wide house at 128 West 72nd Street to Daniel O’Day in September 1891. The millionaire paid the equivalent of just over $2 million in today’s money for the high-stoop, four-story residence.

Born in Ireland in 1844, O’Day was brought to America by his parents when he was one-year-old. He began a business transporting oil in 1865 and by 1876 had constructed a large system of oil pipelines. By now he was a vice-president of the Standard Oil Company, an officer in several other firms, and a director in many others.

O’Day and his wife, the former Louisa Newell (who went by Eliza) had four sons and eight daughters. They summered at their massive Deal, New Jersey estate, Kildysart. Much of Eliza’s entertaining focused on her daughters as they were introduced to society and married. And the O’Days’ prominence in society warranted press attention across the nation.

On May 5, 1898, for instance, the Chicago Tribune announced, “The marriage of Miss Menevive O’Day, a daughter of Mr. Daniel O’Day, Vice President of the Standard Oil company to Mr. Henry Dickson Morrison, a son of Mr. T. W. Morrison of Plainfield, N.J., took place yesterday afternoon at the O’Day residence, 128 West Seventy-second street.”

The first of Florence O’Day’s debutante events was on December 19, 1903, when Eliza “gave one of the largely attended teas,” according to The Sun. The article added, “The reception was followed by a dinner and a dance. On Monday night Mr. and Mrs. O’Day will give a dinner, theatre and supper party for their debutante daughter.”

…among the stipulations in the will was “As long as she remains unmarried she is to have the use of the Seventy-second street residence and its contents and the stable property at No. 242 West Sixty-ninth street.”

Three years later, on April 16, 1906, Florence was married in the Church of the Blessed Sacrament to John William Hallahan, 3d. The Telegram reported, “Mr. and Mrs. Daniel O’Day gave a bridal breakfast after the church ceremony at their home…for about 200 relatives and friends.”

Florence’s parents had returned home from Europe only weeks before the ceremony. Daniel O’Day, according to the New York Herald, “had been in poor health from overwork for more than a year.” Almost immediately after the wedding, Daniel and Louise sailed for Paris again “on the advice of John D. Rockefeller, who urged [Daniel] to take a vacation.” With them were four of their daughters.

On September 13, 1906, O’Day died suddenly at Royan in the south of France. The New York Herald reported, “The immediate cause of death was the bursting of an artery in the stomach. The end was unexpected.”

The following month the New York Herald reported, “Daniel O’Day’s fortune, which is estimated in the millions, with the exception of a few small bequests, is left to his widow, Eliza O’Day…and his twelve children.” The will made certain that Eliza should remain faithful to her husband even after his death. The newspaper entitled the article “Mrs. O’Day Loses If She Remarries,” and noted that among the stipulations in the will was “As long as she remains unmarried she is to have the use of the Seventy-second street residence and its contents and the stable property at No. 242 West Sixty-ninth street.”

In 1909 the O’Day estate sold the West 72nd Street house. By now the exclusive residential tenor of the street was changing and the New York Press remarked that the new owner, Douglas C. Green, “will alter the building for business purposes.”

Green hired architect Alfred H. Taylor to do the first of two metamorphoses to the brownstone. His plans called for removing the stoop “and fitting the two lower stories as stores, finishing the building with an ornamental façade of Harvard brick,” reported The New York Press.

Green was a 1904 graduate of Yale University. He collaborated with three classmates, James H. Brewster, Jr., Edward C. Ely, and Alexander M. McClean to renovate the mansion into a bachelor apartment above the storefront. All four of them moved when the alterations were completed. Edward Ely acted as the manager of the building.

While the apartments were initially intended for single men—and indeed its tenant list filled with other Yale graduates—Ely leased at least one of them to a woman, Mrs. Adele Marie Rique, founder of the University for Soul Education and the Circle of Universal Freedom. She announced in 1909 that the classes of university “are now being continued at No. 128 West Seventy-second Street.”

A reporter from The Washington Post traveled north to interview her in June 1911. His article described her apartment as a “rather stately salon with its high wainscoting, its great mantel and deep fireplace and pictured walls.” She told him, “We take no medicine, ordinarily, but we are not cranks—else we would have no soul freedom. Our prayers and our exercises keep us on good health, and we never mention the condition that is opposite to health…We practice the mastery of the soul over the body, and we simply use common intelligence to keep well.”

Only a month later Madame Rique was in court on a charge “of violating the medical laws by teaching the principles of the Advanced New Thought Cult, of which she is the leader,” as reported by The New York Press. She countered that “she does not cure ills of the body, only those of the soul…We heal the mind. We do not bother with bodily ills.” When the prosecutor asked if she had not prescribed facial creams for a witness, she replied smugly, “I suggested the use of the facial creams and massage because I saw the lady needed them, for I observed that her face was full of blackheads.”

Although he continued to manage the building, Edward Chappell Ely moved out in 1914. On November 21, The New York Times reported in November 21 that he had married Sara Louise Carfoot Pollock. The article noted, “Mr. and Mrs. Ely will extend their honeymoon trip into a tour around the world going first to India, Japan, and China.”

As mostly well-heeled single men occupied the commodious apartments, the ground floor was home to J. F. Sylvester’s golf shop. But when he was drafted in 1917, he was forced to liquidate the store. His advertisement read, “I have been caught by the draft and my entire stock of clubs, bags, balls, and everything for the golfer’s need is on sale at prices that must mean an absolute clearance.”

“…Our prayers and our exercises keep us on good health, and we never mention the condition that is opposite to health…We practice the mastery of the soul over the body, and we simply use common intelligence to keep well.”

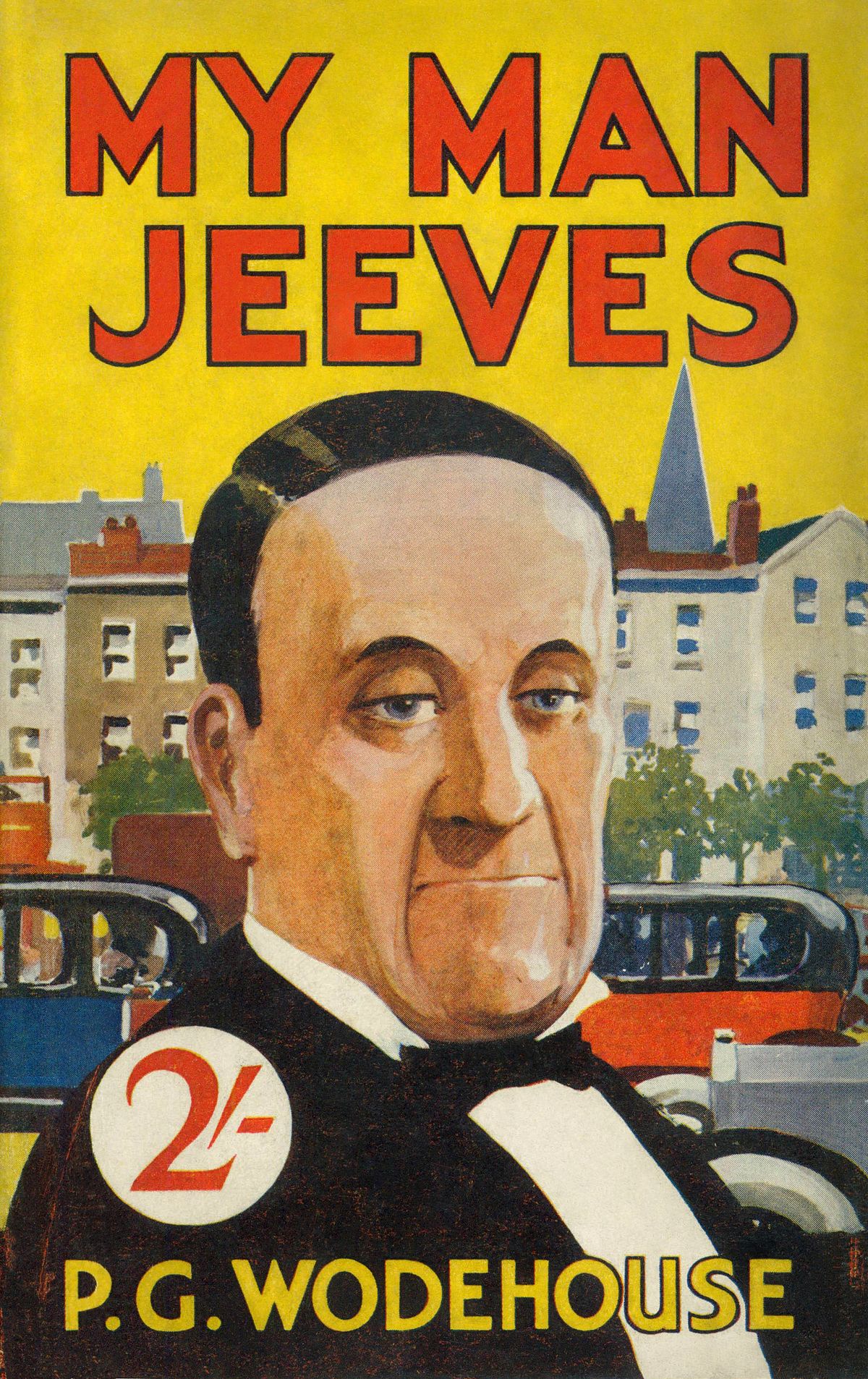

That same year, in August, Edward Ely leased an apartment to Pelham G. Wodehouse and his wife, the former Ethel May Newton. He had earlier written songs with Jerome Kern, and was now writing lyrics for Broadway songwriters and drawing praise from the likes of Richard Rodgers and Ira Gershwin. Wodehouse’s great fame, however, would be a result of his later humorous writings under the name of P. G. Wodehouse.

The former golf shop became the office of real estate firm F. R. Wood & Co. in 1918. And in 1920 the second-floor shop opened as Marie Antoinette’s Tea Room, which Valentine’s City of New York said, “makes a specialty of tea and waffles.” A full dinner of Southern dishes cost $1.25 (about $15.50 today). Both businesses would operate from the address for years.

Then, in 1935, the East River Holding Co. purchased the building and initiated its most significant transformation. Architect William J. Minogue stripped off the front and replaced it with a sleek Art Modern façade, accented by streamlined storefront and a large, oval show window at the second floor. There were two apartments per floor above the commercial spaces.

One of the two original commercial tenants was The (New) Sonia Serovia School of Dancing. Over the next decades a variety of shops would come and go. In 1967 Olga Oshrin took the second floor for her Olga Oshrin—Knits Unlimited shop. It sold hand-knit items. It remained until 1969 when it moved slightly down the street to 211 West 72nd Street. In 1973, Susan Abbott and Terry Eisen opened the design studio and shop, Walrus. Their single product was a versatile pad. According to Ruth Robinson writing in The New York Times, “It is when their creation is rolled up around its matching pillow and buckled to form a hassock that it looks like a walrus, or so Miss Abbott and Miss Eisen insist. Unrolled to its full dimensions of 75 inches by 30 inches, the pad seats three comfortably or sleeps one.”

In 1991, Poona Classic Cuisine of India operated from the ground floor, followed by Thai 72.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

128 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 128 Columbus Avenue:

Meet Jade Oh!