The West End Club[house] and International Sunshine Society

by Tom Miller

In 1883 real estate operator, Margaret Crawford began construction on five upscale rowhouses on West 72nd Street, between Columbus Avenue and Broadway. The avenue-wide street was developing into what the West 72nd Street Association would describe five years later as “the model street of the city.”

The well-known architect Gilbert A. Schellenger designed the homes in the Renaissance Revival style. Completed in 1884 they were four stories above a high basement level, with a high stone stoop rising to the parlor floor level.

Eben S. Allen Pawling and his wife, Amelie L. Pawling, purchased 134 West 72nd Street. As was common at the time, the title was put in Amelie’s name. Interestingly, before the couple sold the house in December 1889 for $55,000 (about $1.6 million today) Amelie had legally changed her first name to Ethel.

Two months before the sale The West End Club was formed. The New York Times reported its purpose was “to promote intercourse among the members and provide a clubhouse.” The fledgling organization leased the former Pawling house from its new owner, William C. Adams at a yearly rent of $3,300, or about $8,000 per month today.

Exclusive men’s social clubs routinely took over mansions within post residential neighborhoods. The elegant interiors with carved mantels, costly paneling and sweeping staircases created an aristocratic setting for the clubrooms. The upper floors contained rooms for members to stay when, for example, they were in town on business during the summer months while their homes were closed for the season. The New York Herald mentioned “The West End Club house is at No. 134 West Seventy-second street. The interior is luxuriously fitted up.”

The organization held a yearly pool tournament in the house. On January 20, 1895 the New York Herald reported on the end of that season’s contest, saying in part “The games were keenly watched by many spectators, including a large number of women.” A more surprising event took place later in the year. On November 13 the New York Herald announced: “HAPPENING TODAY; Musical bicycle ride of the West End Club of No. 134 West Seventy-second street, evening.”

Unlike the West End Association, which was concerned about conditions on the Upper West Side and relentlessly lobbied for improvements, the West End Club seems to have been a purely social organization. Gatherings in the West 72nd Street house were always entertaining—like the New Year’s Eve party on December 31, 1896. The Press reported that the group “had a supper and vaudeville entertainment.”

The West End Club remained at the address through April 1898, when owner Henry B. Slaven began leasing it to well-to-do residents like the widowed Julia M. Crane. Mrs. Crane appeared in the newspapers for social events like the “pretty home wedding” in the house on June 3, 1902. Her daughter, Elizabeth Voorhies Crane, was married to I. Edgar Livingston that evening. The guests of the society wedding came from as far away as Long Island and New Jersey.

On November 13 the New York Herald announced: “HAPPENING TODAY; Musical bicycle ride of the West End Club of No. 134 West Seventy-second street, evening.”

Following Julia M. Crane in the house was another wealthy widow, Mrs. Kate L. Gilbert and her daughter, Kathleen. A newspaper noted “The Gilberts divide their time between their Manhattan home and their Patchogue country-seat.” Kate appeared regularly in the society pages. Her entertainments often centered around the International Sunshine Society, like the Board and Council meeting held in the house on the afternoon of April 26, 1904. The group, composed almost entirely of women, sought to bring “sunshine” into the lives of shut-ins or the sick, by sending greeting cards and flowers.

But the news on November 5, 1904 had nothing to do with the International Sunshine Society. Brooklyn Life reported that Kate had announced Kathleen’s engagement to Frank Earle Hayward. It was a prodigious social match. Kathleen, who was a niece of General Grenville M. Dodge, was marrying into a prominent family. The groom was the son of millionaire John W. Hayward and had grown up in the Hayward mansion next to the Stuyvesant Fish residence on Gramercy Park.

The wedding took place in the 72nd Street house on January 25, 1905. Because the groom’s brother, William Tyson Hayward, was a prominent resident of Brooklyn, Brooklyn Life called the wedding “of considerable Brooklyn interest.” The article noted “Following the ceremony there was a very largely attended reception. Throughout the house there were lavish decorations of American Beauty roses and palms, and Mr. and Mrs. Hayward were the recipients of a large array of costly gifts.”

Later that year Henry B. Slaven died. His widow, Ellen, sold the 72nd Street house to Woodward E. Black. At the time of the transaction, West 72nd Street was noticeably changing. Its width, once so attractive for private homeowners, now made it popular as a major cross-street. In 1910 The New York Sun would lament that the street had entered the “boarding house stage of deterioration.” And, indeed, an advertisement in The Evening Telegram on June 13, 1908 read “Boarders Wanted—Large and small rooms’ excellent table; parlor, dining room; subway and elevated stations; telephone, summer rates.”

Although certainly not so well-to-do as Mrs. Crane or Mrs. Gilbert, the residents were nonetheless financially comfortable. Among the boarders in 1911 were Dr. J. A. Bodine and Mrs. David Burtis—both of whom landed in newspaper articles that year for far different reasons.

On March 26, The Evening Telegram reported, “A handsomely gowned, refined woman of about sixty years, became hysterical to-day while walking along Broadway and fell in front of a garage at No. 1,602 Broadway.” Mrs. Burtis may have been overwhelmed by the crowd that collected. The newspaper said, “a policeman from the West Forty-seventh street station pushed his way through and took charge of the woman.” Overcome with emotion (the newspaper said she fell “in a fit”) Mrs. Burtis was taken in an ambulance to Flower Hospital.

Dr. J. A. Bodine, too, was hospitalized later that year. Early in September Dr. E. H. Quinn amputated a man’s lower limb at St. John’s College Hospital on Long Island. Upon reaching his home in Manhattan that evening, he “collapsed and sent for his friend, Dr. Bodine,” according to The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Bodine had Quinn removed to a private sanitarium where he performed an operation. The article said “Dr. Bodine had reached his home only a few hours when he, too, began to suffer the effects of a strange malady.” On September 14, 1911 The Brooklyn Daily Eagle ran the headline “Doctors Near Death.” Luckily both physicians recovered but it was months before they were able to resume their practices.

In 1923 the owners of the property, Redstone Holding Corp., hired architect Samuel Cohen to completely remodel it. The brownstone front and stoop were removed, and the façade pulled forward to the property line. There were now a store at the ground floor and an office space above. The upper floors were converted to “bachelor apartments,” a term which meant that there were no kitchen facilities in the apartments, not that only men were accommodated.

As a matter of fact, Elizabeth Ackerman and her family lived in one of the apartments by the end of the summer. The girl was 16-years old—a fact that landed her parents in jail on August 12 that year. In the early hours of that morning police raided the Columbus Dancing Academy on the third floor of 300 West 58th Street. It was, in fact, a speakeasy run for and by Filipinos. Twenty-two underage girls, including Elizabeth, worked there as what was delicately termed “dancers” by the police. A female detective testified “that fifty of the 100 Filipinos in the place were intoxicated and that couples were dancing very close on the floor.”

The girls’ parents were arrested. The following day Magistrate Corrigan dismissed the case because of “flimsy evidence produced by the police.” The Daily News reported “two spankings in the court corridor followed.”

The office space was home to the American Society of Miniature Painters at the time, while the shop became home to Edith Hansen’s beauty parlor. Edith ran into problems in 1926. Mrs. Cora E. McNutt came to the salon on September 15 concerning facial blemishes. Edith said she could remove them, and Mrs. McNutt’s husband paid the $125 fee up front (a considerable $1,810 in today’s money).

Then things were horribly wrong. The Sun reported “The treatment, according to Mrs. McNutt, consisted of putting liquid and powder and surgical plaster on her face, then suddenly ripping off the plaster, an operation which she said caused great pain.” Worse than that, a consulting physician later said that “she had probably been disfigured for life.” Edith Hansen was arrested in her apartment. She appeared before a judge on December 20. According to The Sun, “Mrs. McNutt appeared in court heavily veiled.”

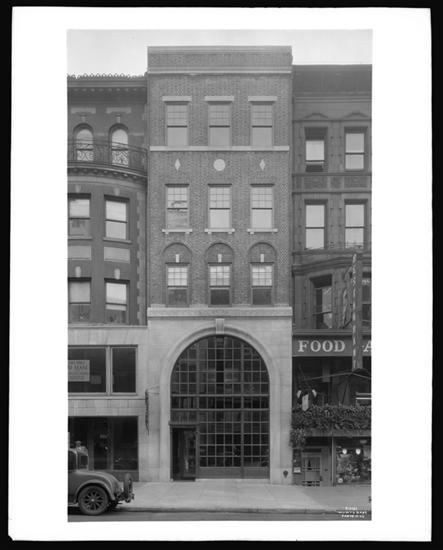

Major change would come to the structure following is sale on April 9, 1930 to real estate operator Joseph S. Ward of L. J. Phillips & Co. The firm hired architect Nathan Korn to make substantial renovations to the first through third floors for its offices. Korn’s make-over resulted in a two-story limestone commercial base which framed an enormous arch. The top three floors received a brick-faced neo-Colonial facade. L. J. Phillips & Co. would occupy the three lower floors, while the top two held one apartment each.

J. Phillips & Co. was one of the oldest real estate firms in the city, organized in 1873 by L. J. Phillips. It was one of the first such firms to establish branch offices, opening its West Side office in 1886 at Ninth (later Columbus) Avenue near 70th Street. As it moved into its new headquarters in September 1930 The New York Times commented that the building “has been rebuilt with an attractive façade, the feature being the bronze and limestone front two stories in height.” The very public apartment renting department was on the main floor, the brokers’ department, partners’ offices and conference rooms were on the second, and the third held the bookkeeping offices. “In the basement is a plan room, where will be maintained files of plans of all west side apartment houses,” said the article.

The firm remained in the building until around 1948. That year the Florana Studio operated from the address. An ad promoted “Face lifting without surgery” and promised that its exclusive method “restores firm, youthful contour, erases eye-lines, wrinkles. Freckles, light scars removed! Bad skin condition Corrected!” The clinic would remain in the space for several years.

Only an hour and a half later the building superintendent, Miguel Vasquez discovered a grisly scene in the basement. Turner’s body was on the floor of Dr. Saez’s safe. Police said he had been stabbed nine times.

The building was renovated by its new owner, Dr. Jose Saez, in 1957-58, resulting in his medical office on the ground floor, offices on the second and third, and now two apartments each on the upper floors. He leased the third-floor office to Chess Review magazine. Around the beginning of October 1962 chess master Abe Turner was hired as a clerk for the monthly periodical. He was described by The New York Times that year as “one of the top players in the country.” Already working in the office at the time was 38-year old Theodore Smith, a clerk-typist.

Abe Turner was a man of several interests. The New York Post said he “had written several unproduced TV plays and acted in bit parts in several locally produced films.” But, said the article, he “had one consuming passion in life, chess.” The 38-year old Turner was a bachelor who lived with his father.

The basement of the building was used as Dr. Saez’s storeroom and lab space. A large walk-in safe that held medical records was normally left open. On the night of October 25 Abe Turner left the office to head home. Only an hour and a half later the building superintendent, Miguel Vasquez discovered a grisly scene in the basement. Turner’s body was on the floor of Dr. Saez’s safe. Police said he had been stabbed nine times.

Within hours Theodore Smith was arrested at the 135th Street YMCA. He admitted to the murder, explaining “the Secret Service had told him to execute Abe Turner.” He was booked on a charge of homicide and sent to Bellevue Hospital for a mental examination.

The magazine remained in the third-floor office at least through 1969. In 1984 the second floor was home to the Bjorkman & Martin Studio of Dance and Exercise. In the ground floor that year was the Gartner’s Hardware store. Other tenants over the coming years would be the Shorin Ryu Karate Dojo and the Lavar Hair Design salon.

The bronze muntins of the ground floor windows were removed at some point to accommodate a modern storefront. At the same time a second door to access the store was installed. But despite those changes, the 1930 renovation for a real estate company is remarkably intact.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

134 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the business currently at 134 West 72nd Street:

Meet Seung Min Lee!