Medical Quack and a Butcher’s Dose of Reality

by Tom Miller

In 1894 real estate operator R. Clarence Dorsett hired architect C. P. H. Gilbert to design a townhouse on the southern side of West 72nd Street, between West End Avenue and Broadway. Gilbert was best known for his high-end residential design, and at 27-feet wide, this could only be described as a mansion.

Construction took nearly two years to complete. As the finishing touches were being completed, the firm of Archer & Pancoast sent two “fixture hangers,” John O. Lawson and Francis Burkett to the site in February 1896. The men installed lighting fixtures throughout the house. Tragedy occurred when the two men left work on February 6. They parted ways at Columbus Avenue and 72nd Street, Lawson going south towards Brooklyn and Burkett heading off to catch the streetcar.

A few minutes later Burkett was focused on catching the cable car and did not notice the delivery wagon approaching. He was knocked to the pavement by the one of the horses and the rear wheel of the heavy wagon drove over his body, crushing him to death.

The completed house was sold to banker Harvey Edward Fisk of Fisk & Harvey. He and his wife, the former Mary Lee Scudder, had two sons, Harvey, Jr. and Kenneth. Fisk was actively involved in the development of the Upper West Side and in 1894 had purchased a large parcel of land on 70th Street just east of West End Avenue where he erected a seven-story school building.

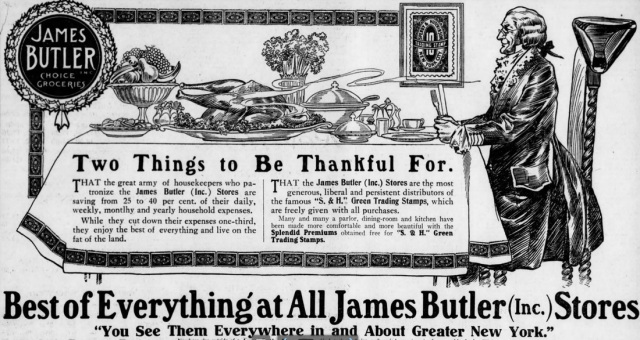

Fisk sold the house in May 1903 to James Butler. Born on a farm in County Kilkenny, Ireland in 1855, Butler had come a long way. In the early 1880’s he invested his life savings to open a grocery store on Second Avenue. By now he had a chain of stores—all with green and gold interiors—and significant personal fortune. Three of his stores were on Columbus Avenue and another on Amsterdam Avenue. They were upscale, catering to the wealthy families along Central Park West and the Upper West Side avenues. Butler and his wife, the former Mary Ann Rourke, had five children, Beatrice, James, Jr., Genevieve, Pierce and William. They maintained a country estate in Tarrytown, New York, near the John D. Rockefeller estate. He was prominent among the racehorse community and built the Empire City Racetrack in Yonkers.

Tragically, Mary died “suddenly” in the house on November 6, 1906 at the age of 51. The following year he donated land to the congregation of the Religious of the Sacred Heart of Mary and funded the establishment of Marymount School in Tarrytown in Mary’s memory.

Mary Butler was visible in society. On February 14, 1904, for example, The New York Times reported “Miss Jennie Louise Butler of Philadelphia had a large reception given for her yesterday afternoon by her aunt, Mrs. James Butler, at the latter’s residence 230 West Seventy-second Street.”

Tragically, Mary died “suddenly” in the house on November 6, 1906 at the age of 51. The following year he donated land to the congregation of the Religious of the Sacred Heart of Mary and funded the establishment of Marymount School in Tarrytown in Mary’s memory.

The businessman was now thrown into the role of single father—a task somewhat lessened by the presence of a significant domestic staff. A devout Roman Catholic, many of his philanthropies and entertainments revolved around religion. On February 10, 1911, for example, The Standard Union reported that he “gave a dinner to thirty of his friends last night at his home, 230 West Seventy-second street…in honor of Archbishop John M. Farley. Mr. Butler sat at the head of the table, and on his right was Archbishop Farley.”

One-by-one the children grew and married. At a dinner in the house on January 15, 1914 he announced the engagement of Beatrice to Dr. Philip D. MacGuire. The Sun mentioned that she was educated at the Visitation Convent in Georgetown, “and she has passed much of her time since leaving the convent at her father’s country place, Eastview, Pocantico Hills.”

The engagement of James Jr. (“son of James Butler, the famous grocer and horseman,” noted The Herald Statesman) was announced one year later, on January 22, 1915. The social status of the groom-to-be was reflected in his memberships to the Point Judith Polo Club, the Gedney Farms Club and the Richmond County Hunt Club.

Genevieve’s engagement was announced in January 1917. The Sun mentioned that she “has been prominently identified with the younger contingent in Tarrytown, where her father has a beautiful country place.” She was married to Walter Elliot Travers in St. Patrick’s Cathedral four months later. The ceremony was performed by Cardinal John Murphy Farley. Afterward a large reception was held in the West 72nd Street mansion.

It was not long afterward that James Butler left number 230. He leased it briefly to Dr. Francis R. Ward who styled himself an “electro-medical scientist.” He had left Chicago after, according to him, “his advertised claims were attacked by the newspapers.” It did not take long for New York newspapers to follow suit.

On April 20, 1919, the New-York Tribune wrote, “He does not accept ‘any chronic cases, like tuberculosis, heart disease or cancer’—this despite his advertised willingness to treat ‘deep-seated, chronic and lingering ailments.’” He explained that he was not a member of the Academy of Medicine because “they won’t let me.” Nevertheless, he was making a fortune. The article said that he had a “gross income of $300 a day, or about $9,000 a month.” That would be equal to just under $1.6 million a year today.

Investigative reporters were dogged. The New-York Tribune began another article saying, “Dr. Francis R. Ward, who quit his medical practice in Chicago in 1913 after his concern was charged in the Federal court with quackery, is now doing a thriving business in New York.” The article noted he “maintains sumptuous offices” at 230 West 72nd Street.

Ward sued the New-York Tribune for half a million dollars in damages following the articles. And so surely the editors were thrilled to publish an article days later, on June 19, 1919, saying that Ward had been found guilty of “fraud and deceit” of a patient, Julius B. Grond. He had been promised he would be cured of a malady within one month following payment of $100. He sued saying that the “representations were untrue and known to be untrue by the defendant.”

Despite the uproar, Ward announced in The Standard Union on January 18, 1920 that his Electro Medical Office at 230 West 72nd Street was “the finest equipped office of its kind in America. Scores of electrical appliances of intricate mechanism and all that Dr. Ward has found valuable for the alleviation of chronic ailments can be seen.”

In 1932, the architectural firm of William Higginson & Son converted the house to retail space on the ground and second floors, and apartments in the upper stories. A streamlined two-story Art Moderne storefront projected to the property line. Not surprisingly the store space became a James Butler Grocery Co. store. By now Butler had more than 1,000 stores, the sixth largest chain in the United States. Just before his death in 1934, he purchased the former Otto H. Kahn mansion on Fifth Avenue for the Convent of the Sacred Heart and its school. More than 3,000 mourners attended his funeral in St. Patrick’s Cathedral.

Ward announced in The Standard Union on January 18, 1920 that his Electro Medical Office at 230 West 72nd Street was “the finest equipped office of its kind in America. Scores of electrical appliances of intricate mechanism and all that Dr. Ward has found valuable for the alleviation of chronic ailments can be seen.”

In 1949, the former grocery store became home to Fischer Brothers kosher butcher shop. Another renovation to the building, completed in 1950, resulted in a penthouse, invisible from street level, which held one apartment.

During the 1971 police strike a reporter from The New York Times, Lesley Oelsner, went door-to-door asking proprietors if they were nervous having no protection. The manager of Fischer Brothers replied in true New York fashion. “So they break in. What are they going to steal? Meat? Let them take it.”

By the late 1990’s the shop had slightly changed its name to Fischer Brothers & Leslie. In 1999, the partners celebrated their 50th anniversary by rolling back prices on lamb chops and chickens to 1949 prices.

The second-floor space was home to New York State Assemblyman Scott Stringer’s office in 2000 through 2005. Fischer Brothers & Leslie was still downstairs, deemed by The New York Times food critic Florence Fabricant that year “the only good kosher place” on the Upper West Side.

Today the second floor is still home to an assembly member’s office, and Fischer Brothers & Leslie continues to operate at street level. And a glance above reveals the intact, elaborate brownstone façade of what was once the home of two of Manhattan’s wealthiest families.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

230 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 230 West 72nd Street:

Meet Paul Whitman!