View of 253 West 72nd Street from southwest. Courtesy NYC Municipal Archive LINK

The Hotel Westover

by Tom Miller

In the first years of the 20th century, residence hotels straddled the line between transient hotels and apartment buildings. While tenants signed long-term leases, as in apartment buildings, they enjoyed the amenities of hotels—maid service and an upscale, communal dining room, for instance. By the 1920’s several were appearing along West 72nd Street, until recently a strictly residential thoroughfare.

In 1925 J. Burgess Book, Jr., president of the Book-Cadillac Hotel in Detroit, Michigan, assembled a syndicate known as the 253-263 West 72nd Street Corporation for the purpose of erecting another high-end residential hotel. He hired the New York architectural firm of Schwartz & Gross to design the structure, yet brought in a Detroit architect, Louis Kamper, to assist in the project.

The 22-story Hotel Westover was completed in 1926. Its spartan neo-Renaissance decoration was limited, essentially to the second and third floors. Here were Renaissance inspired carved panels and blind balustrades that gave the illusion of Juliette balconies. There were six stores at street level. On the first floor was the building’s restaurant–as expected in a hotel, none of the apartments had kitchens.

The Hotel Westover had a variety of tenants. Among the initial residents were Howard K. Brooks, vice-president of the American Express Company, and millionaire real estate developer Edward West Browning. Browning’s office was on West 72nd Street and he had erected two nearly identical apartment houses at 42 and 118 West 72nd Street.

Twenty-six-year-old Eleanor Bantley lived here in 1930. An actress, things in her life were not going well. On March 6 she was found in her apartment with both wrists slashed. The New York Sun reported, “She had also taken twelve poison tablets.” She was taken to Bellevue Hospital where her condition was listed as serious.

on October 15, 1937, Mayor Fiorella La Guardia addressed a luncheon of the West of Central Park Association.

In the meantime, Edward West Browning drew considerable attention to himself and to the Hotel Westover because of his penchant for teen-aged girls, some of whom he adopted. It all culminated on June 23, 1926, when the 51-year-old developer married 16-year-old Frances Belle Heenan, known as “Peaches.” Within the year she filed for divorce, accusing him of keeping a live goose in the bedroom, forcing her to remain nude in the apartment, and tossing telephone books at her.

Still living in the Browning apartment in 1934 was Dorothy Sunshine Browning, whom he had adopted before meeting Peaches. Reporters caught up with her and her fiancé, on February 5 that year, after her adoption caused concern at City Hall. “Daddy is a fine father,” she told them, “and he planned for us to be married at the Little Church Around the Corner this afternoon. We will be married, however, just as soon as everything is fixed up.”

Four months later, on June 22, Browning’s chauffeur knocked on the apartment door, but got no answer. He entered to find his employer unconscious on the floor, having suffered a cerebral hemorrhage. Three days later The Sun wrote, “Edward West Browning, well-known real estate operator who won the nickname of ‘Daddy’ because of his passion for adopting people, was pronounced ‘out of danger’ this afternoon.” Nevertheless, he was still in a coma and was paralyzed on his left side.

Browning would never return to his Hotel Westover apartment. He was taken to a private hospital in Scarsdale, New York, where he died on October 11. The Capital Journal noted, “with him when he died was Dorothy Sunshine Hood, whom Daddy had adopted before his marriage to ‘Peaches,’ and her husband.” (Despite Dorothy’s daughter-like devotion at the end, it was Peaches who got the bulk of his estate.)

The ground floor restaurant was also a gathering spot for large events. On June 2, 1937, for instance, a tribute dinner in honor of the late Dr. Simon Baruch was held here, and on October 15, 1937, Mayor Fiorella La Guardia addressed a luncheon of the West of Central Park Association.

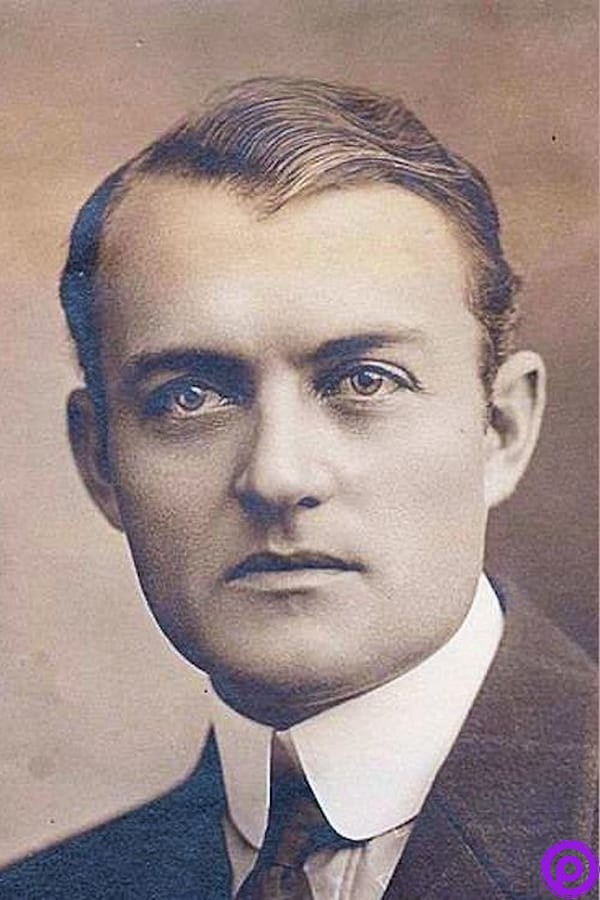

Veteran actor Richard Bennett was a resident of the Hotel Westover in 1938. He was the father of actresses Constance, Barbara and Joan Bennett. He suffered an accident in the hotel that year when a carpenter allowed a heavy door to close on his hand, breaking his thumb. Bennett sued the hotel for $100,000 in damages (closer to $1.86 million today) for “losses of professional engagements.” On January 10, 1939, The New York Sun explained, “he was forced to give up a contract to play the role of Gramps in ‘On Borrowed Time’ when the pain from his injury prevented him from carrying on the role.”

The Hotel Westover became the headquarters of an international black-market ring after World War II. David Warner had four sons and the war had dispersed all but one of them throughout the world. Lewis, who was 22 and a former USAR lieutenant was now working for an American airline company in Berlin. Robert, a former Navy lieutenant was working in Shanghai. Oscar, too, had been a lieutenant in the Navy and was operating what United States Army agents called a “so-called export-import business in Paris. And Al Warner was an exporter in New York.

David and Al Warner ran the operation from the Hotel Westover apartment. On August 12, 1946, The Times Record announced, “The U. S. Army reported today that its agents had smashed a multi-million-dollar global black market ring operated by a New York family with sons in Berlin, Paris, New York and Shanghai.” The article continued, “The officers said they had found evidence that the Warners were dealing in almost every kind of black market goods, including diamonds, cigarettes, rugs, silks, penicillin, currency, perfumes, watches, clothes and the like.” The Democrat and Chronicle added that the average “take” in China alone was $10,000 per week.

In 1961 the building was renovated. Along with the stores there were now a “cabaret bar and lounge” on the ground floor, and a two-story penthouse with eight apartments on the 23rd floor and “club rooms” on the 24th. The new street level bar was the Café Sahbra, deemed by the Canarsie Courier as “the only Israel night club in America.” Along with dinner (strictly kosher according to advertisements), patrons were entertained by sohara dancers and the orchestra of Bob Philiss.

“The U. S. Army reported today that its agents had smashed a multi-million-dollar global black market ring operated by a New York family with sons in Berlin, Paris, New York and Shanghai.”

On the 24th floor was the Holiday International Penthouse Club, which offered events like “Jazz on the Terrace” on August 19, 1964. It survived until 1970 when the floor was converted to two apartments.

The building’s most notorious incident occurred on January 4, 1973, after Roseann Quinn, a 28-year-old teacher at St. Joseph’s School for the Deaf, failed to report to class after Christmas recess. A worried colleague went to her apartment on the seventh floor. The superintendent opened the door and they found Quinn’s body on the sofa. Detectives said she had been raped and stabbed 14 times.

Quinn frequented the singles bar across the street, W. M. Tweed’s. A neighbor told police, “She had no regular boyfriend, but she was the type of girl who would have a guy in if he brought her home.” John Wayne Wilson was arrested and charged with her murder. His lawyers told reporters on February 2 they would rely on the insanity defense. But it would never come to that.

Five months after the murder, Wilson hanged himself in the Manhattan House of Detention for Men. Shockingly, a spokesman for the Department of Correction, Agenor Castro, said it was the sixth suicide in city jails that year. “There were 11 last year,” he added. Roseann Quinn’s murder was the inspiration for the 1975 novel Looking for Mr. Goodbar and for the 1977 film of the same title.

Now known as the West Pierre, the building’s entrance has been remodeled and the limestone base inexplicitly painted gray. Above, despite a hodgepodge of window air conditions that made the façade look like a climbing wall, little has changed.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

253 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 253 West 72nd Street: