Twilight Sleep and other Unwarranted “Advances”

by Tom Miller

In 1701, Cornelius Dyckman acquired 94 acres of open land centered around what would become Broadway and 73rd Street. His daughter, Cornelia, married Jacob Harsen and the couple built their farmhouse in 1763 at approximately what would become Amsterdam Avenue and 70th Street.

By the outbreak of the Civil War, what had been a sprawling farm was already plotted out for development. Although actual construction would not begin for years, in 1868 deed covenants were put in place that restricted the block front between 72nd and 73rd Streets facing what would become Riverside Drive. Described as a “covenant against nuisances,” it prohibited the land’s use for any business “which may be in anywise dangerous, noxious, or offensive to the neighboring inhabitants.”

The far-thinking covenants may have been put in place with the anticipated Riverside Park and Drive in mind. The concept of the elegant park had been proposed three years earlier. By 1879, the first stage of the park–from 72nd Street to 85th Street–was completed.

John Schureman Sutphen was well-known in real estate circles in the 19th century. He began buying property on what would become Riverside Drive in 1868 when he purchased lot 4. By the end of the century, he owned the entire Riverside Drive block front from 72nd to 73rd Streets. His expressed intention was that “wealthy and select families” would “purchase and live there and would secure the future character” of the neighborhood, according to The New York Times later.

When Sutphen died in his home at 160 West 72nd Street on November 17, 1900, the Riverside Drive property passed to his son, also named John Schureman Sutphen, and his wife, the former Mary Tier Brown.

The Sutphen and Brown families were both wealthy and socially-connected. Both traced their roots to colonial America. Mary’s father was founder and owner of the nationally-known David S. Brown & Co. soap firm. Guests at the couple’s fashionable St. Thomas’s Church wedding on December 16, 1890 included Mayor Hugh J. Grant and General William T. Sherman.

An 1888 graduate of Columbia University, John S. Sutphen was a founder and partner in the Sutphen & Meyer glass and mirror firm. He was also a director of the Lincoln Trust Company and sat on the boards of The American Lloyds and the Bronx Savings Bank. He eventually retired from the glass business so he could devote his time to managing his father’s extensive real estate holdings.

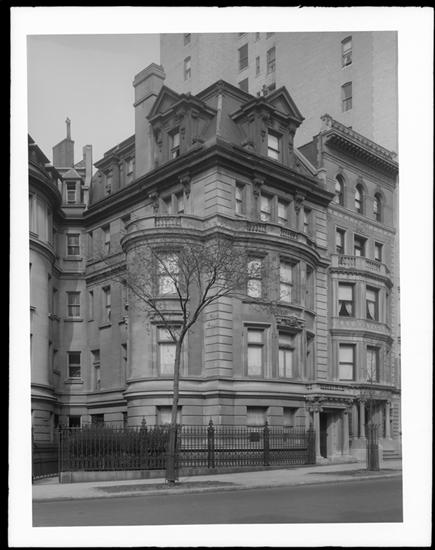

The couple wasted no time developing the Riverside Drive-West 72nd Street properties, including one mansion for their own family. On June 12, 1901 mansion architect C. P. H. Gilbert filed plans for a residence at 311 West 72nd Street, at the foot of Riverside Drive. They called for a house “five stories in height, with a tiled mansard roof.”

The Sutphen and Brown families were both wealthy and socially-connected. Both traced their roots to colonial America. Mary’s father was founder and owner of the nationally-known David S. Brown & Co. soap firm.

Simultaneously Gilbert laid plans for the house next door at 1 Riverside Drive for the Sutphen’s acquaintances, Frederick Charles Prentiss and his wife, Lydia. The deed Sutphen had drawn up for the couple had assured that Gilbert would design their home. It not only indicated that the building lines of the Prentiss house were to conform to the Sutphen residence, but designated the architect.

Gilbert handled the oddly-shaped corner by placing a pie-shaped courtyard between the two homes. It provided a full sidewall of light and air to both homes found normally only in stand-alone or corner structures. The plan also allowed for views of the park and the river from the Sutphen residence.

The Sutphen mansion was completed on December 27, 1902. Gilbert had created a handsome Beaux Arts limestone home, which complimented, but did not match, the Prentiss house. The entrance was dignified by a portico with ornate Scamozzi columns. It upheld an intimate balustraded balcony off the piano nobile, or main living and entertaining level.

Bowed bays on both the front and side provided additional balconies at the fourth floor. The style’s French influence burst forth at the fifth floor. Here, a steep mansard was punctuated by dramatic copper-clad dormers.

The family, including daughter Mary and sons David Arthur and John Jr., had lived at 18 West 83rd Street. A few months after moving into their new home another daughter, Hyacinth Adeline–named after her paternal grandmother–was born.

Both John and Mary were involved in organizations relating to their heritage. John was a member of the Sons of the Revolution and the Holland Society, and Mary was a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution and the National Society of Colonial Dames. John was also a member of the Columbia and St. Andrews Clubs and of the Blooming Grove Fishing and Hunting Club.

The first of the Sutphen children to leave the 72nd Street mansion was Mary. She was married to Lewis Atwood Knott on April 10, 1912 in St. Ignatius’s Church on 87th Street at West End Avenue. She wore her mother’s wedding dress. Nine-year old Hyacinth acted as flower girl. Following the ceremony a reception was held in the Sutphen home.

In 1915 Mary was alerted to an alarming problem on the Riverside Drive block by Angie Booth, who lived at 4 Riverside Drive. Angie had discovered that her new neighbor at 3 Riverside Drive, Dr. William H. Willington Knipe, had opened his New York Home of Twilight Sleep in the house.

Twilight Sleep was a relatively new practice in the United States. The idea was imported from Germany and was intended to reduce the pain suffered by women giving birth. It no doubt worked, since it relied on injections of morphine to deaden the pain.

Angie Booth and Mary Sutphen joined forces to shut down the sanitarium. They notified Knipe on September 30 “that they objected to his place.” When he ignored the women, they filed suit in December, carefully using the exact wordage in the 1868 deed covenants. Their suit alleged “The business is noxious and offensive to the neighboring land owners.”

They won the battle and the sanitarium was closed.

Mary’s focus soon turned to happier issues. On May 25, the following year John Jr. was married to Adelaide Hedden Raynolds. Their wedding, too, was held in St. Ignatius Church.

John had just graduated from Princeton. He worked in Ridley’s Confectioners and would quickly rise to vice-president. The couple moved into 215 West 98th Street. Adelaide was a strikingly handsome woman and her looks would result in a fatal tragedy six years later.

John and Adelaide summered in Allenhurst, New Jersey. They invited a friend, Adrian Arthur, to be their weekend houseguest in August 1921. The trio attended the annual masquerade ball at the Allenhurst Hotel on Saturday night, August 27. The New York Times noted it “caps the social climax for the fashionable beach colony.”

While Adelaide and Adrian were dancing, a young Cuban man, Salvadore Laborde, attempted to cut in. The Cornell University junior made the excuse of saying he thought he knew Adelaide. The Times reported they “both informed him of his mistake.”

Undaunted, after a few minutes Laborde returned. Adelaide “repulsed him” and “Arthur seconded her sternly.” But Laborde’s conduct became even more objectionable, according to witnesses.

The incident seemed to be over until Adelaide and Adrian went downstairs to the grillroom for refreshments. Laborde was there and, according to Adelaide’s testimony later, “The fellow jumped out of a telephone booth without warning” and landed a punch to Adrian’s face. Adrian fell backwards, striking his head on the concrete floor. He died from a skull fracture.

By the time of the horrifying incident, Hyacinth was attending Smith College. John and Mary were spending less time in the West 72nd Street house. Their winters were spent in their lavish home in Ormond, Florida and they summered either in Europe or fashionable resorts. As the family prepared to leave for the summer in 1921, Mary placed an advertisement in The New York Herald hoping to find a position for two servants who were not coming along:

Chambermaid and waitress; am closing my house; wish to place chambermaid and waitress, together or separately. June 1.

(A waitress was a step above a chambermaid. While the chambermaid had the unenviable task of cleaning and scrubbing, a waitress served meals and waited on the family’s wants.)

Unlike the weddings of her siblings, The New York Times reported that it “was arranged with the utmost secrecy.” Bowers, who was 19 years old, was attending Brown University and Hyacinth was still studying at Smith College. Quiet, secretive marriage ceremonies like theirs were certain to raise eyebrows among a suspicious society set.

When the Sutphens returned that fall, preparations began for Hyacinth’s coming out. On December 28, 1921, The New York Herald announced that “Mrs. John Schureman Sutphen…will give a reception with dancing this afternoon in the Plaza for her daughter.”

The last summer that Hyacinth spent with her parents was in 1923. That year the three sailed for Europe where they planned a “motor trip” through England, Wales, France and Normandy. Hyacinth’s St. Ignatius’s Church wedding to Fredson Thayer Bowers was held on November 11, 1924.

Unlike the weddings of her siblings, The New York Times reported that it “was arranged with the utmost secrecy.” Bowers, who was 19 years old, was attending Brown University and Hyacinth was still studying at Smith College. Quiet, secretive marriage ceremonies like theirs were certain to raise eyebrows among a suspicious society set.

Bowers, incidentally, would go on to an illustrious career. He served as a commander in the U.S. Navy during World War II as code breaker. He continued on to become a renowned biographer and editor of scholarly texts.

Six months after the wedding, on May 23, 1925, John S. Sutphen died in the 72nd Street mansion of pneumonia. He was 58 years old. His funeral was held in the same church where he had seen his children married.

Mary retained ownership of the house, but moved to No. 1035 Fifth Avenue in 1927. She converted the mansion to apartments. When she signed a five-year leased on the property, furnished, with A. Bodin in May 1938, it was described as containing “twenty-eight apartments of one and two rooms.”

Mary Tier Sutphen died on September 24, 1949. The estate sold No. 311 the following year. Remarkably, there are still 28 residential units in the house. The once-grand interiors have been stripped bare, replaced with sterile drywall. And C. P. H. Gilbert’s elegant limestone façade is sheathed in decades of grime.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT