The Little King or just the President’s son-in-law?

by Tom Miller

Dr. Juan B. Delgado and his brother Jose were wealthy Colombian fruit growers in the first decades of the 20th century. They augmented their incomes by branching out into real estate investment in New York and in Europe. In 1927 they purchased the four brownstone houses at 330 through 336 West 72nd Street and hired the architectural firm of Blum & Blum to design a modern, replacement apartment building on the site.

Brothers George and Edward Blum devised an unlikely 1920’s take on the Medieval Revival style. Thirteen stories of beige brick sat upon a two-story limestone base. Many of the windows wore cast-stone, crenellated sills, and at the ninth and fourteenth floors whimsical damsel-ready pseudo balconies clung to the façade. On the roof, barely visible from the street, was a penthouse level.

Among the initial residents, was Dr. Juan B. Delgado, himself. It is possible he was avoiding his home country because of ongoing marital difficulties. His wife, Gabrielle Nieto de Delgado, was a nice of General Rafael Reyes, who had been President of Colombia from 1902 to 1910. He had been “involved in litigation” with Gabrielle for several years, according to The New York Times.

In 1928, shortly after 330 West 72nd Street was completed, Delgado obtained a New York divorce decree and instantly married Gertrude Boerisch, who naturally shared his apartment. But, as it turned out, Gabrielle Nieto de Delgado did not go away so easily.

On March 13, 1929, Dr. Delgado died leaving an estate valued at about $12.8 million in today’s money. Almost immediately the Colombian Consulate placed two guards outside the Delgado apartment “to prevent the removal of the effects,” according to the consulate’s attorney. The problem was that the New York divorce was not recognized in Colombia, and a treaty signed between the United States and that country in 1851, “authorizes the South American country to take charge of the property of any of its subjects dying here,” explained The New York Times on April 23.

This is absolutely astounding,” he declared

Gertrude went to court, claiming that “she was entitled to remain there in privacy as the decedent’s widow.” In the meantime, Jose Delgado was en route to New York to argue against Gertrude’s having any entitlement to his brother’s estate. Before he arrived, Judge O’Brien of the Surrogate Court blasted the consulate’s actions.

“This is absolutely astounding,” he declared. “The consulate has exercised more authority than a Supreme Court justice. Supreme Court justices and surrogates, with all their power, cannot put a man in an apartment without a hearing on the facts.” He demanded that the two guards be immediately removed.

In the end, battling the Colombian Government, Delgado’s first wife, and his family was apparently too much for Gertrude. On April 23, The New York Times reported that she had relinquished her claims to the estate, settling instead for 10 percent. Perhaps more shocking was her agreement to be termed Juan Delgado’s “common law widow.”

The building filled with white collar residents, like Dr. J. Joseph McElhinney. His family suffered a string of tragedies starting on October 28, 1930 when his brother, Dennis, was drowned in Barnegat Bay. Just eleven days later, another brother, John, was hit and killed by a taxicab on West Street. The bad luck continued when Dr. McElhinney visited his mother in Point Pleasant, New Jersey three months afterward in January 1931. He caught pneumonia and died there two days later.

At the time of Dr. McElhinney’s death, the rent for a five-room apartment with two bathrooms was about $2,500 per month in today’s money.

Living here in the 1940’s were actors King Calder and his wife, Ethel Wilson. A Broadway leading man and television actor, Calder started his career in 1929 in The Humbug, and appeared in numerous plays, including My Sister Eileen and No Time for Sergeants. Ethel was best known as a television actress, appearing in the series The Aldrich Family and later Colonel Humphrey Flack.

The other residents of the building may have objected to Ethel’s passion—stray cats. In 1946 she told journalist Eleanor Booth Simmons, “I love all animals. I grew up on a farm in Maryland, where there were horses and cattle and dogs and cats, all well fed and cared for, and here in New York I’ve never been able to get used to the overdriven horses and the homeless starving dogs and cats.”

And so, Ethel took to providing dinner for the stray cats in the alley behind the building. Simmons wrote, “There are plenty of stray cats around the apartment house at 330 West 72d street, where Miss Wilson lives.” Ethel believed that feral cats had a way of spreading the word, “Say, there’s a good handout over at No. 330.”

Every afternoon at 5:00 Ethel took pans of food to the alley. As to how she got enough food to feed so many cats, Simmons explained, “Well, her fish dealer is very good about saving cod necks for her, and she boils these and mixes the flaked fish with dry cat food. And she gives them lots of milk.” One imagines that the odors wafting from the Calder-Wilson apartment were pungent, as well.

Odors in the hallway were not what was fishy at 330 West 72nd Street in 1966. Stanley Glucksman was an agent of the Internal Revenue Service. He was arrested and charged with accepting a bribe “to refrain from further tax examinations.” Glucksman resigned from the I.R.S. while under investigation. He was tried and acquitted in 1968. And so, it seemed that Stanley Glucksman was in the clear. But he was quickly charged with accepting a $3,000 bribe from another corporation that had been being audited around the same time. The 46-year-old was found guilty for this charge in Federal Court in January 1970. The New York Times reported he “faces a maximum sentence of 15 years in prison and a fine of $20,000.”

Soglow did not start out to be a cartoonist, he wanted to be an actor.

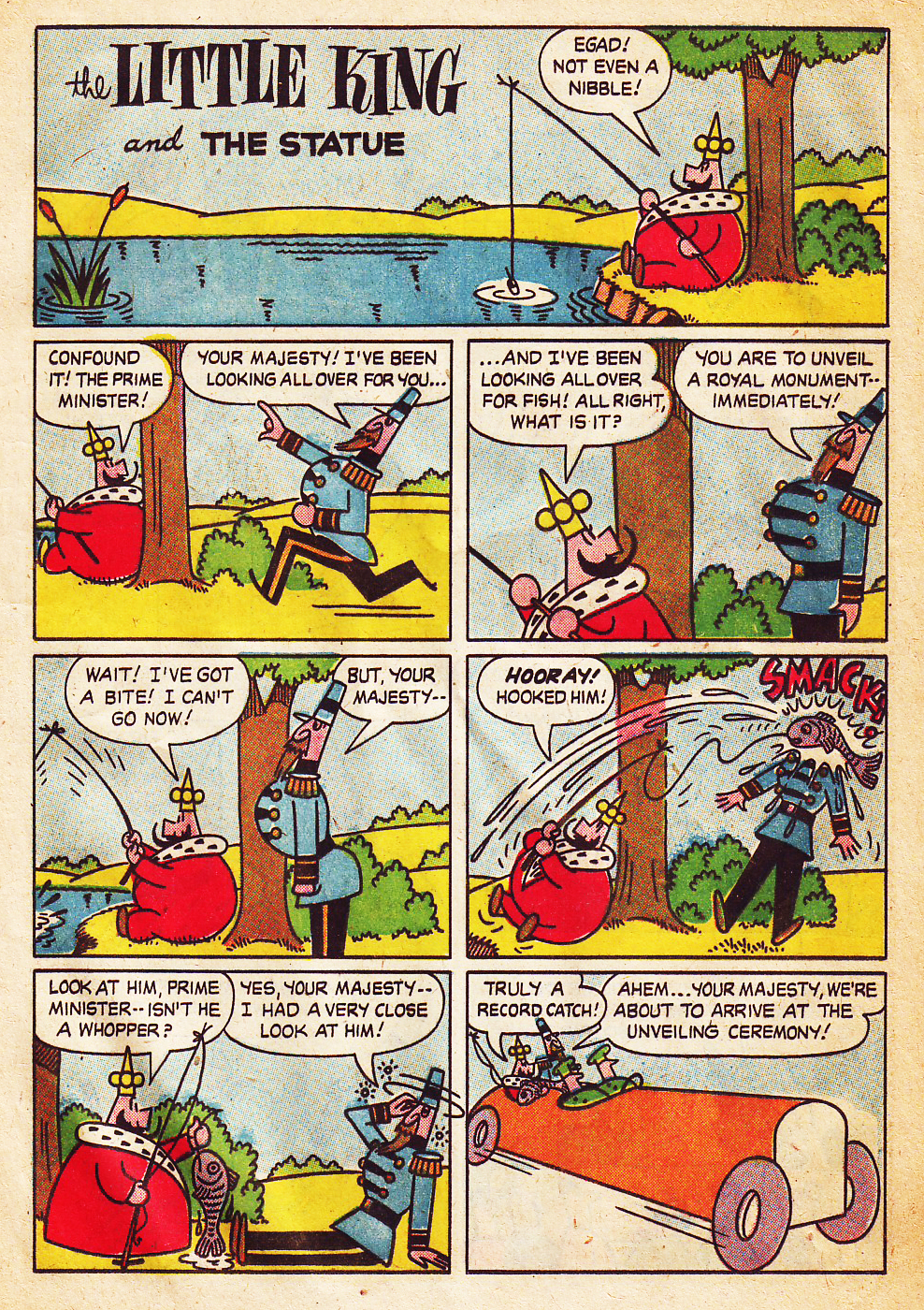

A resident beloved by newspaper readers nationwide was Otto Soglow, the cartoonist who created “The Little King” and other characters for the King Features Syndicate.” Soglow did not start out to be a cartoonist, he wanted to be an actor. Born in Yorkville in 1900, he had dropped out of high school his sophomore year to become a Broadway actor. Instead, he made a living as a dishwasher, errand boy and switchboard operator.

After World War I he enrolled in the Art Students League and started out as a commercial illustrator. Eventually he turned to cartoons, his work appearing in The New Yorker. It was that magazine that asked him to make The Little King a regular character. His strip was eventually featured in nearly 100 newspapers nationwide. But he never achieved his life’s passion.

Following his sudden death in his apartment on April 3, 1975, The New York Times remarked, “Like the character he drew, Mr. Soglow was a frustrated man, baffled, bewildered, thwarted, blocked and defeated…He wanted to be an actor, and he never stopped wanting to be an actor.”

Blum & Blum’s quaint and somewhat playful structure has been slightly altered over the decades. The cornice has been simplified and the windows replaced. But overall, it looks much as it did when the man who built it moved in with his new wife–at least by New York definition.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT