View of 40 West 72nd Street from north. Courtesy NYC Municipal Archive LINK

Priceless Sleep at The Hotel Bancroft

by Tom Miller

The era of opulent private mansions along West 72nd Street was ending in the post-World War I years. High-stooped residences were being converted for business or razed to make way for business buildings and apartment houses. In 1925, the Wellmore Realty Corp. demolished the four four-story houses at 34 through 40 West 72nd Street and hired two well-known apartment architects, Emery Roth and H. I. Feldman, to design a replacement structure.

Completed in 1926, the tripartite, 15-story building was a 1920’s take on the Italian Renaissance. The three-story stone base was embellished with a series of arches which, in turn, embraced double arches at the second floor. Three heraldic-type shields, one with a rampant winged beast, added to the motif. The eleven-story brown brick midsection was nearly unadorned. But the top story made up for that with engaged columns, elaborate stone and terra cotta panels, and brilliant blue tilework within the underside of the arches, a happy surprise for anyone looking up from the street.

The Hotel Bancroft was a residential hotel—essentially an apartment house with amenities of an upscale hotel, like maid and linen service. There were 30 apartments per floor and upon the roof were a sun parlor and “recreation and children’s room.”

Many of the residents were involved in the musical field, like Metropolitan Opera soprano Madame Editha Fleischer. Her schedule was brutal during the opera season of 1931-32. She arrived home on Wednesday October 7 from a tour and the next morning rushed to Worcester, Massachusetts to rehearse for the Worcester Music Festival. The Standard Union reported, “Thursday night she rehearsed until midnight.” Why she decided to come home to the Hotel Bancroft rather than stay one more day in Worcester (her engagement was on Friday evening) is unclear. Nevertheless, as reported by the Standard Union on Saturday, “yesterday she decided to take a nap.”

The diva had slept through her performance. “She became semi-hysterical upon learning the truth,” said the newspaper. It was understandable. The extra-long nap cost her the $1,200 payment she would have received (more than $20,000 today).

That night the police were notified of “the strange disappearance” of Madame Fleischer. She was awakened at about 11 p.m. by “someone paging her in loud and anxious tones along the corridor.” The diva had slept through her performance. “She became semi-hysterical upon learning the truth,” said the newspaper. It was understandable. The extra-long nap cost her the $1,200 payment she would have received (more than $20,000 today).

Theater producer and photographer Abraham Mandelstam created the Intimate Revue Group in 1933, using the Hotel Bancroft as its base of operations. The goal was to create experimental theatrical products and, hopefully, discover new artists along the way. On June 4, 1934, The Brooklyn Citizen reported, “The Intimate Revue Group has arranged for an eminent composer, a writer of lyrics, and one playwright to spend the months of July and August near Harrison, Maine, to whip material into shape for the first of three revues contemplated this Fall.” The article noted, “The present headquarters of The Intimate Revue Group is at No. 40 West 72nd street, New York City.”

A significant interior renovation completed in 1939 resulted in a total of only six to eight apartments per floor, plus two in the new penthouse level.

Among the recognized names living in the Hotel Bancroft in the early 1960’s was violinist and former concertmaster of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Frederic Fradkin and his wife, the former Ruth Mann. A prodigy, Fradkin had first appeared with the American Symphony Orchestra at the age of nine. In 1914 and ’15 he served as concertmaster of the Russian Symphony Orchestra and in 1916 and ’17 held the same position with the Diaghileff Ballet Russe.

He became concertmaster of the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 1918 but was fired two years later for “failure to comply with the instructions of the conductor.” His termination led to the orchestra’s unionizing.

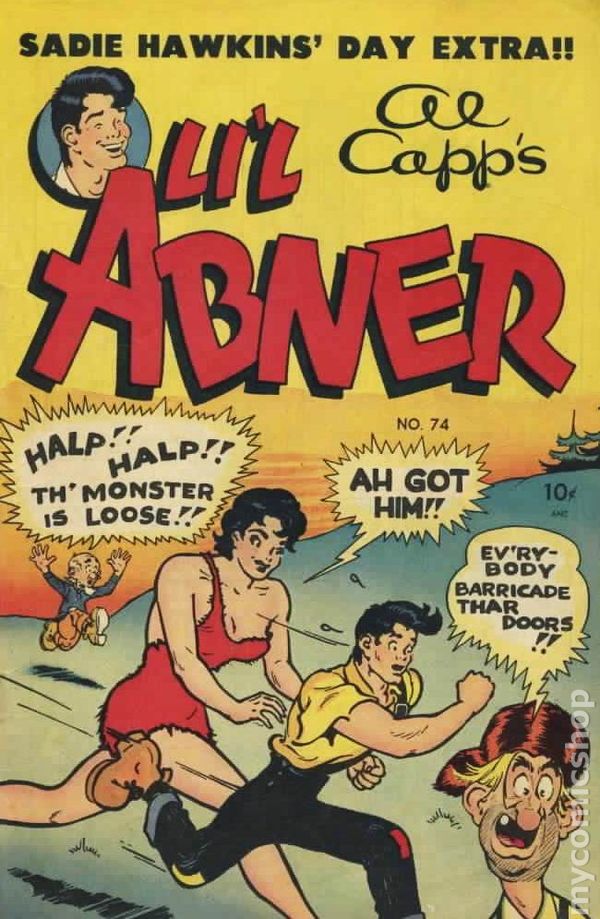

Of course, the Hotel Bancroft was home to a variety of tenants not associated with the music industry. One of them, Otto P. Caplin, was a retired wholesale broker. Interestingly, of his three sons, Al, Jerome, and Elliott, only the latter kept the family’s surname. Al and Jerome changed theirs to Capp. Al Capp was the best-known family member. His cartoons like “Lil’ Abner” were favorites nationwide.

Living in the Hotel Bancroft at the same time as Fradkin and Caplin were Mandel Marcus and his wife, the former Clara Gottlieb. He was president of the Marcus Substructure Corporation founded by his father, which built sections of the New York subway system.

Two of the tenants of the ground floor commercial spaces in 1979 were El Faro 72 restaurant, which touted “authentic Spanish Cuisine,” and Hilde’s Imports.

The hotel status of the building allowed its management to charge higher rents than rent-stabilized apartments. But by the 1980’s the Hotel Bancroft had quietly begun cutting back on amenities like maid service and linens. The New York Times explained in May 1982, “…while apartment leases can run for two or three years, hotel leases are for one year only, resulting in higher increases over the long term. And when a residential hotel apartment is vacated, the rent can be raised to market level.”

One tenant, Gerald M. Philpott, told journalist Christopher Wellisz, “When I moved in three years ago, no mention was made of maid or linen service,” but he eventually realized that older tenants were provided those perks. A review of his lease revealed the stipulation that there would be no such services.

The tenants were “irked” according to Wellisz in a follow-up article on August 1. Jerry Philpott (presumably a relative of Gerald) was head of the tenants’ association. He told Wellisz, “Either you give all services to all tenants, or you should be declassified.” The tenants went to the Office of Rent and Housing Maintenance.

Whether the upheaval prompted a renovation to the building is unclear, however in 1983 the apartments were downsized. There were now between eight and eleven apartments per floor.

The Bancroft was the scene of a horrifying crime in 1990. Musical-comedy actress Marcia Brushingham had lived in a fifth-floor apartment since 1982, and her elderly mother lived on the eighth floor. Marcia Brushingham had appeared in several Broadway shows since her debut in Come Summer in 1968 and more recently had appeared in a revival of The Music Man starring Dick Van Dyke. Her mother suffered from dementia, but the actress refused to place her in a facility. She went so far as to take her along on tour to ensure her care.

…in August 1965 his eight-year-old daughter, Mary, went out too far in the ocean in Florida and drowned. While family members tried to save her, five-year old Marcia wandered off. Her body was found a short time later.

In the meantime, Marcia’s older brother, David, had suffered a series of misfortunes. A jeweler, in August 1965 his eight-year-old daughter, Mary, went out too far in the ocean in Florida and drowned. While family members tried to save her, five-year old Marcia wandered off. Her body was found a short time later. She too had drowned. And then, in 1980, David shot and killed his 18-year-old son when he mistook him for a burglar. His wife divorced him soon afterward. He was acquitted of any crime, in that incident, but the same year he was convicted of writing nearly $18,000 in bad checks, and after violating parole was sentenced to seven years in prison.

Destitute in 1989, according to The New York Times, “David Brushingham arrived in New York…in a beat-up sedan with Florida license plates and asked his younger sister to take him in.” Marcia allowed him to move into their mother’s apartment. “He was to help her care for their mother so that the actress could return to the theater, her friend said.”

Marcia was generous to her brother, telling neighbors “Look, how much can a man take?” She purchased him clothing and gave him money, and when he admired a $750 watch, she bought it for him for Christmas. But then trouble came when a wealthy aunt in Florida became ill. Marcia began flying once a week to West Palm Beach to help care for her and arrange her legal affairs. The aunt made plans to disinherit David, because he had borrowed $7,500 from her in the early 1980’s and never repaid it. He began obsessing about the aunt’s money and suspected his sister of conniving to take the entire inheritance for herself.

On March 5, 1990, a maintenance worker became suspicious of a plywood crate sitting in a pile of garbage at the corner of West End Avenue and 66th Street. He notified police who discovered Marcia Brushingham’s body. Her skull had been smashed with a hammer. David Brushingham was arrested. Investigators later told reporters he had murdered Marcia in their mother’s apartment by hitting her on the head with a hammer. He then pushed the crate to West End Avenue on a handcart.

The horrifying crime was unique in the history of the Bancroft. Throughout its nearly 100 years, respectable and law-abiding tenants have come and gone without incident. Among the better-known residents in the first years of the 21st century was Irish actor Milo O’Shea.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

40 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 40 West 72nd Street

Meet Dr. Debra Kroll!