160 Central Park West

Fourth Universalist Society aka The Church of the Divine Paternity

160 Central Park West

by Megan Fitzpatrick

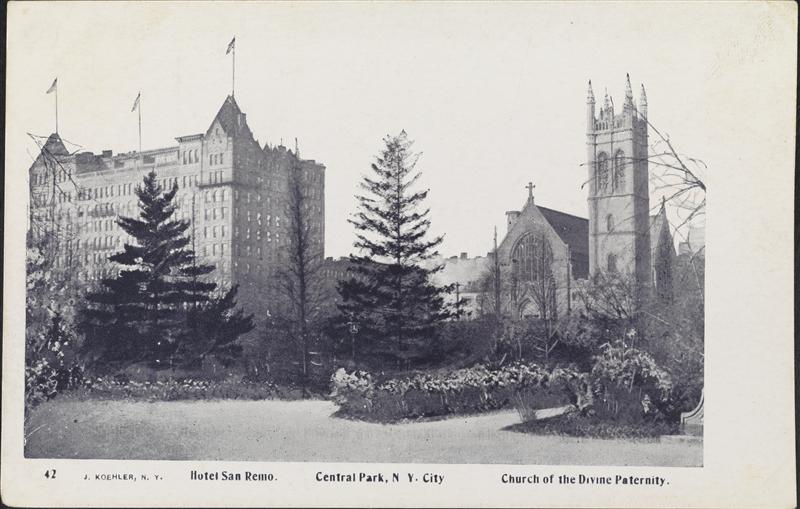

One of New York City’s great houses of worship found its home on the corner of 76th Street, just 120 feet from Central Park. The Fourth Universalist Society or Church of the Divine Paternity, as it was known for much of the 20th century, is a significant Universalist congregation, the last historical Universalist society left in the city, with a history of prominent congregants from Lou Gehrig, P. T. Barnum, and Horace Greeley worshiping at the Church. It laid its claim as a dominant feature in the Upper West Side landscape after the contentious decision to move uptown was made in 1896.

Journey to the Upper West Side

Founded in 1838 as the fourth of seven Universalist societies in New York, the congregation’s first home was a Greco-Egyptian structure on Murray Street. The society officially changed its name to the Church of the Divine Paternity in 1848. The Reverend Edwin H. Chapin proved popular and grew the number of loyal churchgoers. The small church on Murray Street reached capacity so the congregation went searching for a new home. They temporarily worshiped at the former sanctuary of the Church of the Divine Unity on Broadway, while drafting plans to construct a purpose-built sanctuary on 45th Street and Fifth Avenue. The church attracted many members of great wealth and became known as one of the most affluent congregations in the city. It is no wonder they eventually felt the trend to move uptown on the west side. Equally, it’s no surprise the congregation bagged around $700,000 for their Fifth Avenue church.

The sale of the church was unorthodox and shrouded in secrecy, with the buyer choosing to remain anonymous. The Trustees, I. O. Rhines, Hart Brundrett, and J. W. Tingue, who arranged the sale of the large but ‘antiquated’ church, did not know the buyer either and assured the public the new owner would not erect a hotel on the site (New-York Tribune, May 16, 1896). Ultimately, the sanctuary was demolished.

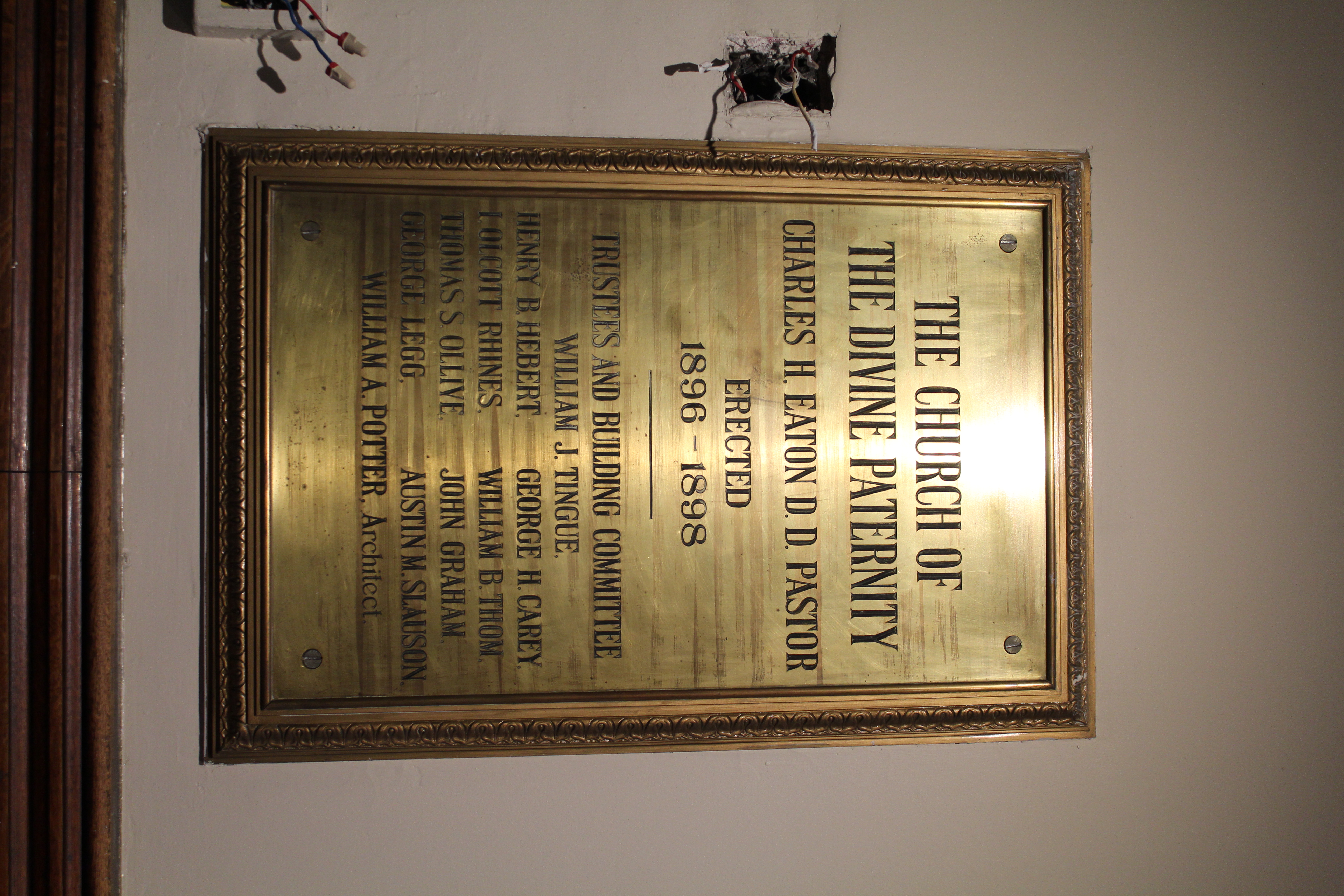

Charles H. Eaton was the pastor at the time and the decision to relocate was largely supported, as many families had moved uptown, however the journey proved challenging. In 1896, six lots were acquired by the church, but negotiations took over three months for the sale to be finalized. This was because of a restriction agreement on the lot on West 76th Street and Central Park West that required signatures from 43 property owners to waive their rights in the restriction of this lot to a private dwelling and allowing a church to be constructed there. The plot opposite the proposed New-York Historical Society cost the church a total of $180,000 (New York Times, October 10, 1896).

The trouble didn’t end there. Another Universalist church, The Church of the Eternal Hope, had moved to West 81st Street just 4 years prior, and with the relocation of a second Universalist church to the neighborhood, one of significantly more wealth and a larger congregation, Eternal Hope was thrown into turmoil resulting in their pastor resigning (New York Times, March 16, 1897). Naturally, resentment grew against the church within the Universalist community. Rev. Eaton stated he had no desire to hurt the other congregation, even addressing the issue at the dedication ceremony on October 3, 1898, ‘in moving to this uptown locality we are not here to block the wheels of other churches or to change the current of religious feeling, but with a determination to join force in this part of town with the other churches for the good of all’ (New York Times, October 3, 1898).

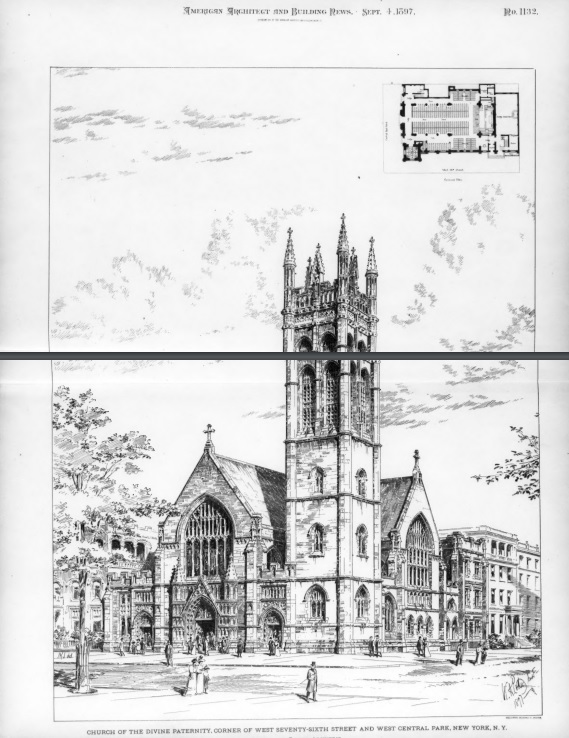

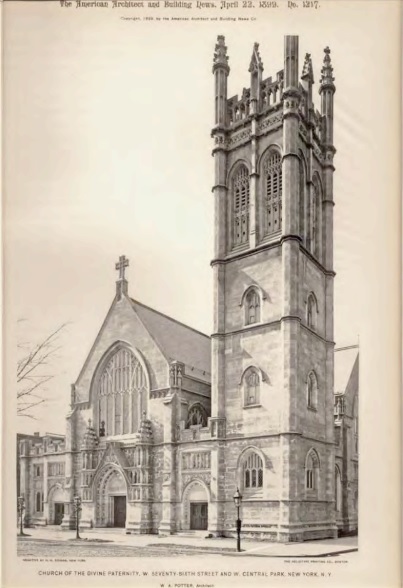

Overall, the new church and parish house was greatly anticipated, with an estimated cost of $450,000 and a design by renowned Gothic-style architect, William A. Potter.

The decision to relocate was largely supported, as many families had moved uptown, however, the journey proved challenging.

1897-1898 – construction of the church

William A. Potter, born in 1842 in Schenectady, was the son of Alonzo Potter, an Episcopal Bishop and acting president of Union College. He specialized in Chemistry at Union College and after graduating, became a professor at Columbia but later followed in his brother’s footsteps and pursued a career in architecture instead. Potter was trained by his brother, Edward T. Potter, and the brothers became well-attributed to Gothic-style architecture and mostly worked on ecclesiastical and academic buildings throughout the northeast of the country. Before the Universalist church, Potter received praise for his impressive St. Agnes Church built in 1890-92.

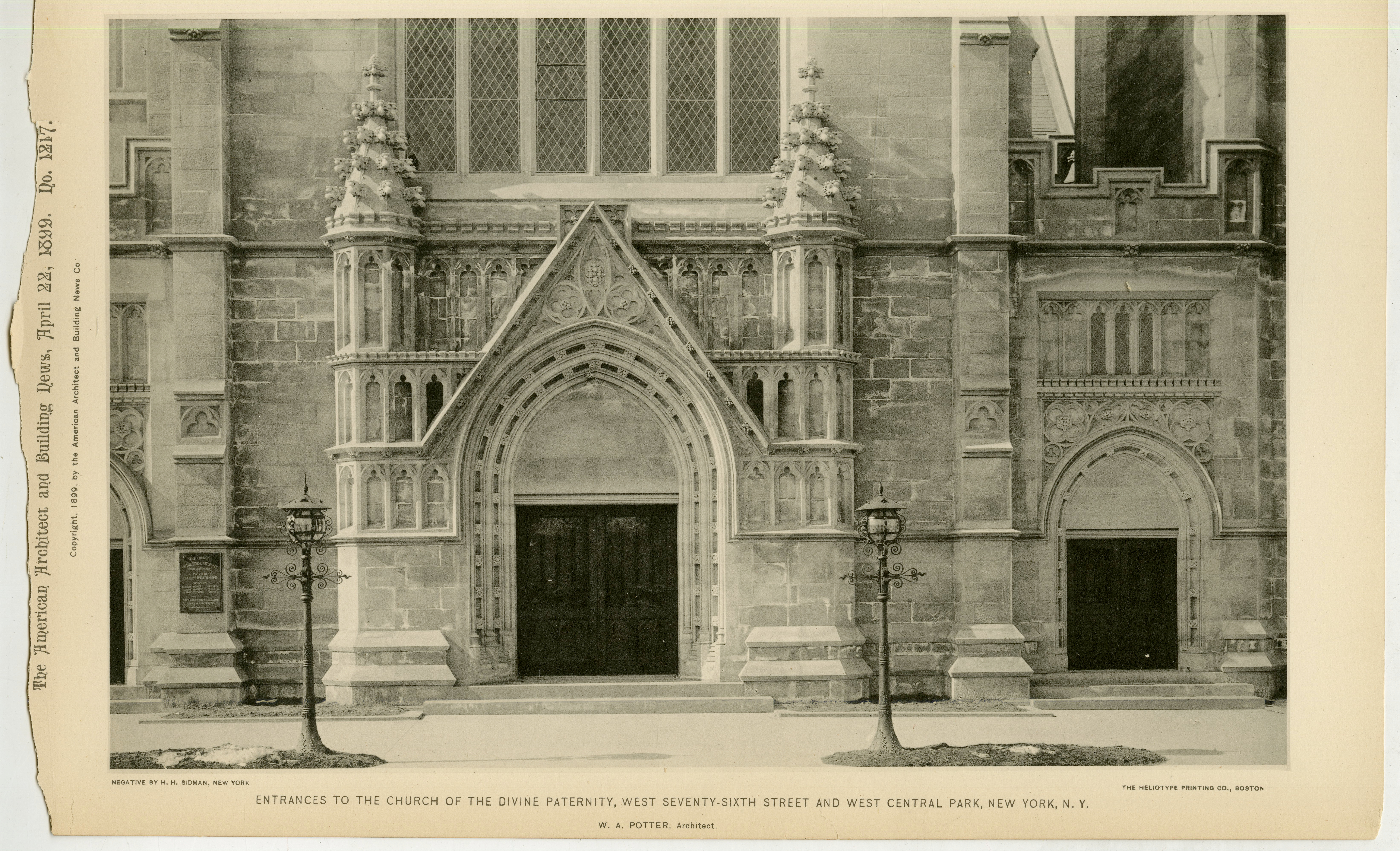

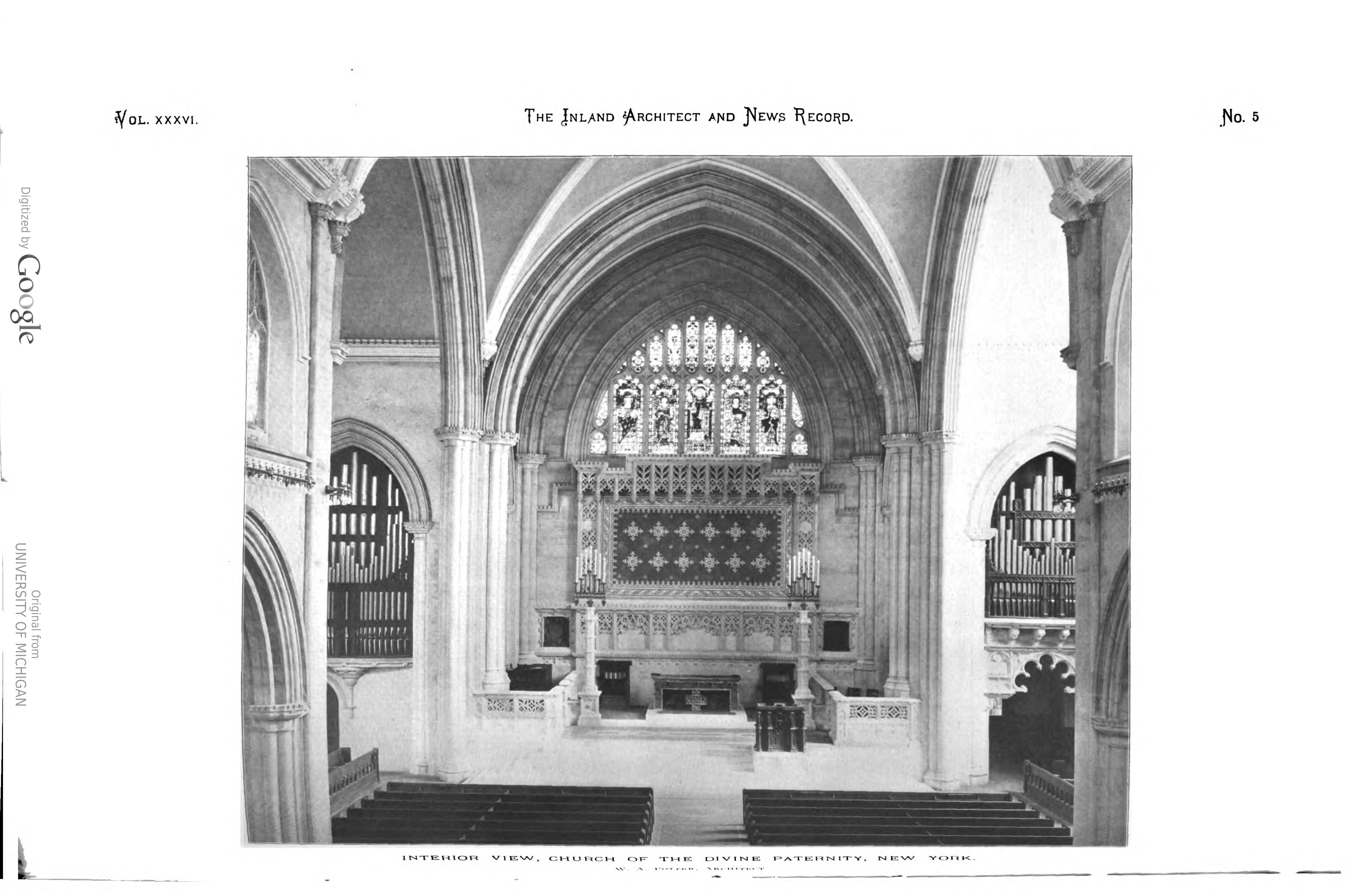

Potter’s style was often described as ‘archaeological’ and Sarah Bradford Landau stated that his Universalist church was ‘the costliest and most ostentatiously archaeological of Potter’s late churches (Landau, 1979). As the Architectural Record noted in 1909, ‘next to a temple of “Christian Science”, a Universalist church may be supposed to be as puzzling a problem as a church architect could encounter (Architectural Record, December 7, 1909). Ultimately, Potter went for an English Gothic-inspired neo-Perpendicular design. The most notable feature is its four-pinnacled corner tower, styled after the bell tower of Magdalen College in Oxford, and can still be seen for some distance despite the many tall structures that have been built since. Four statues were envisioned for the tower niches in the original plans, but these were never carved. The facade elements are remarkable, including an ornate tracery Gothic window above the central pointed entrance, which is flanked by pinnacled structures with striking niches, flush Indiana limestone walls, and drip moldings throughout in typical Gothic style.

At the dedication ceremony, throngs of people gathered at the church to celebrate. Many services were held in addition to music played on a new organ, donated by Andrew Carnegie and his wife, who were notable congregants and contributors to the church. Organist J. Warren Andrews played and would play the organ at the church for the next 34 years.

The new structure received wide praise, even from notable architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright, who attended sermons and whose daughter was married there.

A social history

Charles H. Eaton was appointed the pastor at Divine Paternity in 1881, succeeding Dr. Chapin. He graduated from Tufts College where he earned his Doctor of Divinity and was generally described as a man of ‘liberal thought’ and an incredibly hard worker; under him the church flourished (New-York Tribune, April 15, 1902). His dedication ultimately broke down his health, and he died aged 50 in 1902. Soon after, Rev. Frank Oliver Hall took to the pulpit. Rev. Hall did not first introduce religious tolerance within the church, but it was strengthened under his tenure. Rev. Hall along with Rabbi Stephan S. Wise’s Free Synagogue and the Unitarian Church of the Messiah established Union Services in November of 1910, which sought to unite Christians and Jews in combined sermons with the purpose of discussing various social problems from an ethical standpoint and a spirit of fellowship. The first sermon on November 21, 1910, was packed to capacity, with crowds spilling out into the anteroom to hear the religious leaders preach (New York Times, November 21, 1910). At a church dinner at the Hotel Marie Antoinette on the corner of 66th and Broadway (now demolished), Rabbi Wise defended the controversial decision seen by his congregation to unite with the Unitarians and Universalists, stating the services were not a ‘union of the religions but unity among the religious’ (The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 1, 1911).

The Church of the Divine Paternity would continue to make eyebrow-raising decisions in the period of the early 20th century. In the 1920s, many administrative changes occurred within the church. Rev. Hall had resigned, and Rev. Joseph Fort Newton replaced him. Around this time, history was made with the first woman appointed as a minister within the church and indeed in Manhattan, to assist the new Rev Newton. Helene Ulrich, who wept when she was ordained, was later appointed to the 53rd Street branch of the congregation (New York Herald, March 4, 1922).

The church hosted the West Side Unitarian Church, with Charles F. Potter as pastor, while they were searching for a new sanctuary. The Unitarian Church previously convened at 244 Cathedral Parkway and planned to construct a purpose-built church at 550 West 110th Street (now Congregation Ramath Orah), but plans fell through when the congregation began to experience financial struggles, with the final nail in the coffin being the onset of the Great Depression. They began meeting at the Church of the Divine Paternity in the Spring of 1931, and members discussed a union with the society, but nothing materialized.

Rabbi Wise defended the controversial decision seen by his congregation, to unite with the Unitarians and Universalists, stating the services were not a ‘union of the religions but unity among the religious’

On the night of March 28, 1944, a deadly lightning storm threatened the church’s structural integrity. A bolt struck the top of the high Gothic tower, damaging one of four pinnacles, and causing a shower of masonry to fall onto the street with enough force to crack the pavement (Daily News, March 3, 1944).

The Universalist Society and the Unitarian Church merged in 1961 and the congregation changed its name to The Universalist Church of New York City and then back to its original name, the Fourth Universalist Society. A quick succession of pastors followed with a relatively small congregation in the mid-20th century. A social shift came about within the church when Rev. Richard A. Kellaway was appointed in 1968. Described as a social activist, Kellaway broke away from the conservatism that had developed within the congregation in this period and began to discuss topics such as LGBT issues in his newsletters and sermons. This led to many members opening up about their sexuality and growth in the number of young people in the church. Significant figures in the gay rights movement in New York, such as Barbara Gittings, began attending the Universalist church around this time.

The grand historic church survives in exceptional condition today. Demolition loomed over the church in the 1980s, leading to the establishment of S.O.U.L. (Save Our Universalist Landmark), a partnership between the church and neighbors to raise money to rescue the church from the wrecking ball and from covetous developers (Daily News, March 1, 1987). Commendable restoration efforts continue on this Gothic masterpiece.

SOURCES

Pease, Edmund, ‘Homosexuality at Fourth Universalist Church: An Interview with Edmund Pease’. UU Rainbow History. https://uurainbowhistory.net/homosexuality-at-fourth-universalist-church-an-interview-with-edmund-pease/.

Real Estate Record and Guide, 1897 p. 146.

Dunlap, David W., From Abyssinian to Zion: A Guide to Manhattan’s Houses of Worship. New York: Columbia University Press, 2004.

Fourth Universalist Church, ‘Our History’, https://4thu.org/history/.

Landau, Sarah Bradford, Edward T. and William A. Potter: American Victorian Architects. New York and London: Garland Publishing, 1979.

LPC, ‘Upper West Side/Central Park West Designation Report’, April 24, 1990.

Megan Fitzpatrick is the Preservation and Research Director at LANDMARK WEST!

RETURN TO CENTRAL PARK WEST

Building Database