By Megan Fitzpatrick

On the first day of Black History Month, we’re taking a deep dive into 137 West 71st Street – an Individual Landmark! This rather unremarkable-looking building has quite a history behind it. 137 West 71st Street was designated an individual landmark, not based on its architectural novelty but as the home of celebrated author and civil rights activist James Baldwin (1924-1987).

James Baldwin’s passionate, intensely personal works of fiction and essays in the 1950s and 60s on a range of topics from identity to racial discrimination consolidated him as a critical voice for the black experience in America. Baldwin is considered the first major Black writer since the Harlem Renaissance to write about same-sex relationships. His works, like Giovanni’s Room (1956), pioneered fictional accounts of homosexuality and bisexuality.

Baldwin called the Upper West Side home until his death in 1987, and during his residence at 137 West 71st Street, he wrote some of his most celebrated works, such as If Beale Street Could Talk (1968). The building was also an important social hub with significant figures in music, activism, and literature hosted by Baldwin in the small apartment building. The likes of Maya Angelou, Toni Morrison, Amina Baraka, and Miles Davis, to name a few, were frequent visitors.

Named an individual landmark on June 18, 2019, its designation was significant as one of the very few landmarks celebrating African American or LGBT historical figures. The LGBT Historic Sites Project, who played an important role in its designation, highlighted the under-representation of LGBT landmarks in New York City and the need to diversify landmarks.

137 West 71st Street – before Baldwin

The current facade dates to 1961 after it was altered from an 1890 rowhouse into a five-story apartment house by architect H. Russell Kenyon. The original facade was stripped and replaced with a Modern-style white-brick facade, asymmetrical fenestration, and lowered entrance. Designed by prominent Upper West Side architects Thom & Wilson, the original building was one of four four-story Renaissance Revival-style rowhouses built in the quiet residential neighborhood on 71st street. By the 1930s,137 was the last survivor of the four wedged between newly built apartment buildings. Since Baldwin lived there, few alterations have been made to the simple 1961 facade.

Baldwin’s life and activity in New York City

Born in Harlem, many of Baldwin’s writings and activism were shaped by his early experiences there. Baldwin moved around the city, living in Greenwich Village in his early career and traveling around the world, frequently calling himself a ‘commuter’ and not an expatriate. Baldwin moved to the Upper West Side around 1964 and lived at 470 West End Avenue for a brief period before settling down in his permanent residence at 137 West 71st Street around 1965. His home on 71st Street functioned primarily as a pied à terre in New York City during a time when he traveled frequently and lived in the South of France. It was also a residence for close members of his family, his mother, two sisters, and his niece and nephew. His niece Aisha Karefa-Smart wrote about her time living at her uncle’s house and said whenever he arrived at the Baldwin “headquarters” the energy of the building immediately rose “to a fever pitch as soon as he hit the door.” Baldwin lived in the rear, ground floor apartment and his family occupied the upper floors.

It was in this building where Baldwin wrote some of his later celebrated works as well as correspondence with other prominent literary and cultural figures. Some of these works included Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone (1968), If Beale Street Could Talk (1974), and No Name in the Street (1972). He continued his social activism in the decades he lived in 137, writing many seminal essays and debates on race in America, including his debate with William F. Buckley Jr. and essay on police brutality in 1966, ‘A Report from Occupied Territory’. Soon after moving into the building, he drafted a petition on behalf of the “Harlem Six.” In 1968, Baldwin spoke at a six-hour memorial to Malcolm X at I.S. 201 in Harlem and a few weeks before Martin Luther King’s assassination, he appeared alongside Dr. King at Carnegie Hall for a celebration of W. E. B. DeBois’ 100th birthday. In the same year, Baldwin made a much-quoted television appearance on the Dick Cavett Show, in New York.

Baldwin frequently wrote about LGBT characters in his writings, some of which could be described as autobiographical, however, it was not until later in his life that he spoke about his own sexuality. At a forum in 1982 held by the New York chapter of the gay anti-racism group Black and White Men Together (now Men of All Colors Together), Baldwin discussed his experiences as a gay African American.

While living on the Upper West Side, one of Baldwin’s favorite haunts was said to be Mikell’s jazz club on the corner of 97th Street and Columbus, where his brother David was a bartender. He held a screening of his 1982 documentary I Heard It Through the Grapevine directed by Dick Fontaine and Pat Harley, at the club, attended by Toni Morrison.

Baldwin died in 1987 at his home in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, France and his body was brought back to New York and a ceremony was held at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine.

Throughout Black History Month, we’re exploring significant places of Black History in our neighborhood – come back next Wednesday to see another site!

Read the Designation Report of this Individual Landmark

References:

Images:

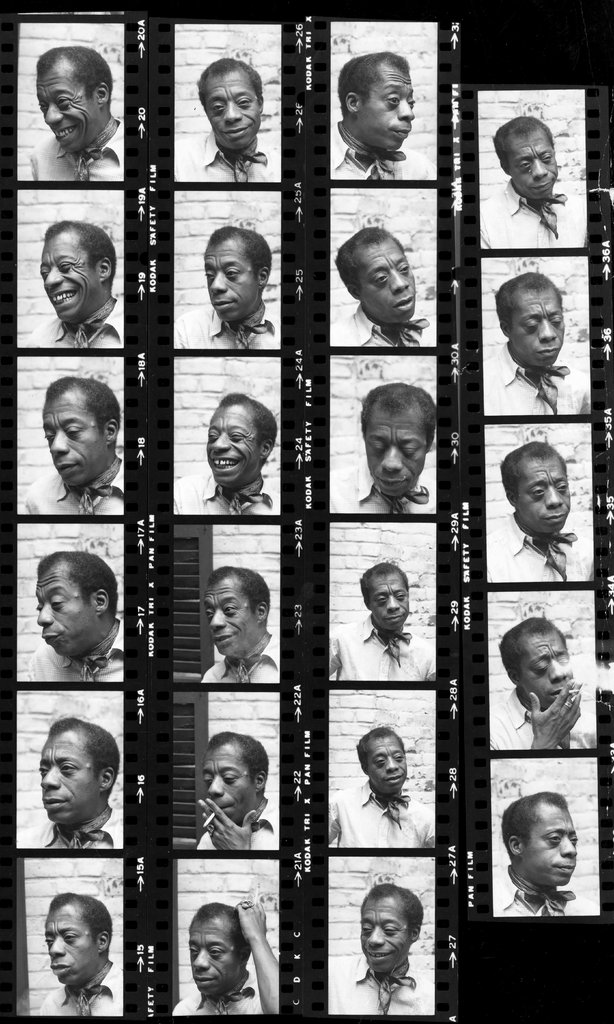

1. Baldwin in the rear yard of 137 West 71st Street, Jun. 26, 1972. Courtesy of Jack Mannig; New York Times.

2. 137 West 71st Street tax photo, 1939. Courtesy of the NYC Municipal Archives.

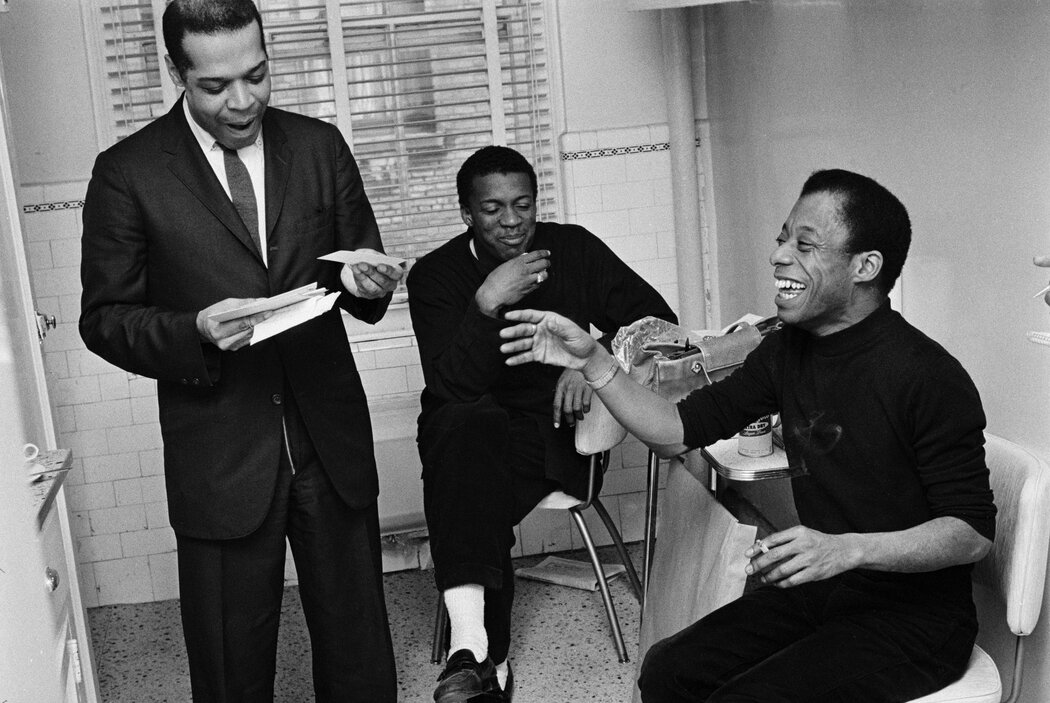

3. Baldwin in his West End Avenue Apartment, 1964. Courtesy of the New York Times, Dec. 17, 2020.

LPC (2019) ‘James Baldwin Residence’, Designation Report.

Davis, Amanda, ‘James Baldwin Residence’, LGBT Historic Sites Project. <accessed 1.30.23>

‘Exploring James Balwin’s Old Haunts in New York and Paris’, New York Times, Dec.17,.2020. <accessed 1.30.23>