Below is the letter sent from LANDMARK WEST! to the American Museum of Natural History regarding the latest stage of their expansion/renovation project. Please contact LANDMARK WEST! by emailing landmarkwest@landmarkwest.org with any questions.

February 19, 2016

Ms. Lisa Gugenheim

American Museum of Natural History

Central Park West at 79th Street

New York, NY 10024

Dear Lisa:

We valued the opportunity to bring together members of LW’s Certificate of Appropriateness Committee, our Board, the Museum’s team, and other stakeholders for a discussion about the Gilder Center for Science, Education and Innovation expansion project on December 17, 2015.

As we stated in our August 25, 2015, letter to President Ellen Futter, we remain keenly sensitive to the impacts of this large-scale project—a major modification to the Individual Landmark and the first expansion of the Museum’s footprint into the public space of Theodore Roosevelt Park since the 1934 construction of the original Hayden Planetarium.[1]

Your presentation and our post-meeting discussion generated many comments. We trust this feedback will help guide the design and planning process as you move from the conceptual stage towards the proposal submitted to the Landmarks Preservation Commission and other agencies.

Jeanne Gang has produced a conceptual design of obvious strength and beauty. While it is premature to pass judgment on the appropriateness of the proposed design in any but the broadest terms, we recognize and appreciate the ways in which it appears to address and defer to the Landmark—for example, its scale and matching parapet and stringcourse heights—while making its own architectural statement.[2] The design and its execution are all the more important because of the site’s prominence at the terminus of the West 79th Street view corridor.

That said, the appropriateness of the addition depends not just on its visual qualities, but also its effects on human experience of the Landmark and its setting. The very presence of a park surrounding the Museum is a significant part of this experience.[3] Therefore, LW! is paying close attention to the relationship between the proposed addition and Theodore Roosevelt Park, placing a high priority on landscape design and defense against short-sighted, incremental development.

LW! and many in the broader community do not accept the assertion that the Museum has the unrestricted right to build in Theodore Roosevelt Park. In pursuing this claim, the Museum leans on a nearly 140-year-old statute that bears little relevance to the present character and density of the Upper West Side, the active function of the Park as a public resource, and the role the Park plays in shaping people’s experience of the Landmark.[4] Any plan that does not establish limits on future expansion into Theodore Roosevelt Park is fundamentally inappropriate.

We urge you to take a holistic approach to architecture and landscape design. Theodore Roosevelt Park is a public park of special significance to the Landmark Museum and the Historic District. It is not a development site. As steward of the Landmark, the Museum also has a responsibility to protect the Park.

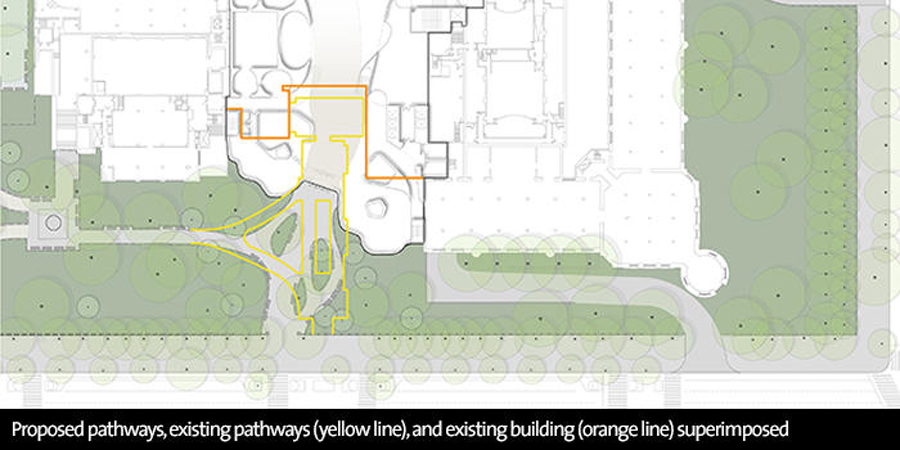

The creation of a grand entrance hall on axis with West 79th Street would trigger a cumulative reorganization of the surrounding park.[5] The addition would occupy 11,000 square feet of well-used, well-loved park space—an intimate neighborhood gathering place—forcing the removal of nine mature trees and altering footpaths, plantings and the existing service road.[6] Yet, missing from the current conceptual design is any coherent vision for the relationship between the new building and Theodore Roosevelt Park. This relationship is as important as the relationship between the new building and the Landmark. The apparent subordination of landscape design to architecture, at this critical stage, raises concerns about the Museum’s commitment to the preservation of quality park space.

A more holistic approach is needed, one that acknowledges the extensive impacts of this proposal on the Park, strives to minimize those impacts, and aggressively seeks out opportunities to maximize public access to existing park space that is currently off limits.

The Museum should create a long-range master plan that ensures the continued existence and quality of Theodore Roosevelt Park. Stewardship of an institution as vast and multi-faceted as the American Museum of Natural History is understandably complex. Growth in and of itself does not justify a piecemeal approach to physical expansion, particularly where significant public assets are at stake. In our discussions, the Museum has referenced the 1874-77 Master Plan. Yet, the current proposal is inconsistent with this Plan.[7] It is time for the Museum to commit to a coherent vision for the Landmark and the Park.

Master Plans are a recognized method to mark anticipated growth when it comes to the expansion of Landmarks—the construction of rooftop additions, infill between previous generations of buildings, and modernization of entrances for enhanced egress, ADA access, visibility and security, to name but a few actions that impact bulk, height and appearance. Without a Master Plan, the result is the ad-hoc accretion of parts that diminish the whole; or worse, the gradual loss of the resource itself.

The Landmarks Preservation Commission has the authority to define and enforce limits on the total area and height of new development that is appropriate for this Landmark and Theodore Roosevelt Park. As a Landmark steward, the Museum must engage in planning that acknowledges those limits.

In addition to a Master Plan, we look forward to reviewing more detailed and developed plans, sections (above and below grade), and elevations for both the building and landscape. Important issues include the proposed landscape design, ramps and driveways, interior connections and circulation, specific programmatic uses (exhibition, educational, and accessory space), materials, and all points of interface with the existing buildings. We also anticipate that additional studies, including the forthcoming and fully annotated Environmental Impact Statement, will shed light on a range of issues including but not limited to urban design, pedestrian and vehicular traffic, environment, street and park lighting, security—affecting the character and experience of this site.

Thank you. We look forward to continuing the discussion.

Sincerely,

Kate Wood

President

cc: Ms. Lisa Gugenheim, Senior Vice President, Institutional Advancement, Education & Strategic Planning

Hon. Tom Finkelpearl, NYC Cultural Affairs Commissioner

Hon. Mitchell J. Silver, NYC Parks Commissioner

Hon. William T. Castro, NYC Parks Manhattan Borough Commissioner

Mr. Namshik Yoon, NYC Parks Manhattan Chief of Operations

Hon. Meenakshi Srinivasan, NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission Chair

Hon. Signe Nielsen, NYC Public Design Commission Chair

Hon. Ruth Pierpont, Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer

Hon. Gale A. Brewer, Manhattan Borough President

Hon. Helen Rosenthal, City Council Member

Hon. Elizabeth Caputo, Manhattan Community Board 7

Peter Wright, Friends of Roosevelt Park

Adrian Smith, Defenders of Teddy Roosevelt Park

Lee Clauss, Community United to Protect Theodore Roosevelt Park

Barbara Adler, Columbus Avenue Business Improvement District

Steve Anderson, Theodore Roosevelt Park Neighborhood Association

Olive Freud, Committee for Environmentally Sound Development

Geoffrey Croft, New York City Park Advocates

Jennifer Nitzky, American Society of Landscape Architects, NY Chapter

Tupper Thomas, New Yorkers for Parks

Peg Breen, New York Landmarks Conservancy

Simeon Bankof, Historic Districts Council

[1] The proposed addition is a significant departure from the brick and stone appearance of the original design concept, with the notable exception of the Rose Center (the structure that replaced the Hayden Planetarium in 2000), which was designed with maximum transparency to reveal the shape of the theater inside.

[2]The attempt to justify the curvilinear elements of the proposed façade based on the Landmark’s historic Romanesque Revival-style features is not convincing.

[3] The NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission designation report for the Upper West Side/Central Park West Historic District (1990), Vol. 1, p15, highlights Theodore Roosevelt Park as “…one of the few parks allocated by the 1811 Commissioners’ Plan…” As the Upper West Side grew around it into one of the world’s densest neighborhoods, the Park has been treated—by the City and the community—as multi-functional public parkland.

[4] Chap. 139, passed in 1876

[5] While we understood that a primary function of the addition was to create axial connections and improve circulation, this was not clear in the drawings. The addition appears to have more volume than usable square footage, raising questions about whether the Museum’s stated programmatic needs could be more efficiently accommodated with fewer impacts on the Landmark and the Park.

[6] The Museum’s presentation did not include any specifics about planned tunneling for infrastructure to provide service truck access. It is clear that this use would expand the Museum’s below-grade footprint and turn the remaining park at this location into an on-grade roof. The anticipated soil depth—realistically only about three feet—would limit opportunities to plant new trees and changing the dappled-shade character of the existing landscape of oaks and elms.

[7] The proposal moves the façade inward and incorporates the 1931 Powerhouse as a finished façade.