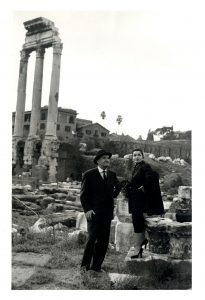

Edward Durell Stone and Maria Torch Stone, Special Collections, University of Arkansas Library

Hicks Stone is a NYC-based architect and author of Edward Durell Stone: A Son’s Untold Story of a Legendary Architect (Rizzoli: 2011). Recently talking about the influences on his famous father’s work, Hicks said, “Dad lived in the Torre dell’Orologio during his grand tour of Europe in the late 1920s. He quite literally faced the Piazza San Marco. Every morning that he left his apartment, the Palazzo Ducale and Basilica San Marco would greet him.” The detail in those buildings in Venice and other parts of Europe clearly inspired the filigree screens he later integrated into many of his buildings.

Stone’s interest in patterns of light and shadow went even further back to his childhood in Arkansas when he was fascinated by the way light was dappled as it streamed through wooded areas. Stone’s buildings including the US Embassy in New Delhi, India (1954) and the beautiful facade of his own townhouse at 130 East 64 Street reflected this artistic focus.

It was in 1959, that the aesthetics of the building he designed for A & P heir Huntington Hartford attracted much attention and both positive and negative discussion. The view of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) was that the art exhibited represented Hartford’s preferences and his own definition of modern art which resisted MoMA’s rigid insistence on defining modern art as non-representational. Hartford stoked this animosity by hiring Stone who had designed the Museum of Modern Art. He also needled MoMA by having his new building incorporate a number of layout features of the earlier building. MoMA went as far as asserting that Hartford’s collection was not modern art and sued him to block his plan to name his museum Gallery of Modern Art.

The powerful New York Times architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable, wrote very positively about the design:

“…Inside the new museum there is much more than meets the passing eye. The irregular shaped building is only about 96 feet on its longest side, but its plan is an accomplished demonstration of one of the basic principles of architectural design—the expert manipulation of space by an expert hand…The theme is dignity and formality, rather than exhilarating spatial fireworks. This interior planning is the building’s conspicuous success, an achievement to command considerable admiration…The Hartford Gallery will provide a sybaritic setting for some interesting, offbeat shows that New York might otherwise not see. The building works well, poses no challenges, asks no hard questions and gives no controversial answers.” (New York Times, February 25, 1964)

Asked if his father anticipated the turmoil provoked by the building and the art collection it held, Hicks said, “I am sure that virtually the entire Stone office was concerned about the building’s overt historicism, even Dad was (He had designed the project in Venice and on his return, he had wondered if he had gone too far). This would have been circa 1959, and incorporating historical allusions in architecture ran counter to the canon of International Style modernism. One associate, Ernie Jacks, wrote about the building in his unpublished memoir, The Elegant Bohemian. “The building’s concept was a total departure from anything the office had done before — very historical, very sentimental, very romantic. We were in uncharted waters…The Boss (Ernie’s nickname for Edward Durell Stone) was worried.”

The museum into which Hartford had poured millions, opened in 1964. It failed after five years. After a period as a NYC- run cultural enterprise, it was extensively renovated and has operated since 2008 as the Museum of Art and Design.

The background of this short-lived museum is intertwined with the tumultuous lives of Stone and Hartford. Hicks said that his father was modest. He was, surprisingly, a somewhat insecure man, which likely led to his drinking.

Stone had established a career. But, it was floundering before he met Maria Torch on a transatlantic flight in 1954. It was love at first sight, they were married within months. Maria, Stone’s second wife, and Hicks’ mother, is generally credited with turning her husband away from the bottle and managing and organizing business operations.

While Stone was reticent about promoting himself, Maria was not shy about taking every opportunity to support and advance her husband‘s career. “It was perfect for her,” said Hicks. It was a role she took on with verve. Her efforts were successful over the ten years before they divorced.” Passionate in a good way at first, later in a bad way,” said Hicks.

Hartford at the time of the museum controversy had long captured media attention. His hugely extravagant investments and dissipated lifestyle had drained his wealth and wrecked his health, though he is said to have regretted nothing.

Over time, MoMA broadened its definition of modern art to be more inclusive. The Huntington Hartford Museum building, although controversial in its time, might today be appreciated as an unequivocally original way to push back the proclivity at the time for buildings that featured tall, impersonal sheets of glass that reached up to the sky. This was a trend Stone hated, according to his son.

Today, although the facade is dramatically altered from Stone’s design, the building is a presence at Columbus Circle. Its history is a reminder that people, their passions and buildings are a large part of what defines a neighborhood.