133-143 West 65th Street

by Tom Miller

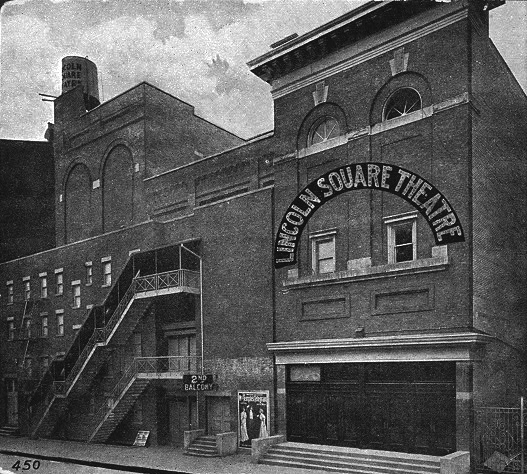

In 1905, developer John L. Miller contracted architect John B. McElfatrick to design a theater on the west side of Broadway, between 65th and 66th Streets. The lobby of the theater would be accessed through the Broadway Arcade, while another entrance on West 65th Street led to the upper floor studios and 21 dressing rooms.

McElfatrick focused greatly on fire protection—fire being a constant fear of audiences at the turn of the last century. A month before its opening, the New-York Tribune reported, “The Lincoln Square Theatre is the first theatre in New York built under the exacting new city fire laws.” The architect went beyond the regulations, however. The article continued:

Special care has been taken to separate the stage from the auditorium in case of need. Instead of the ordinarily required asbestos curtain, to sever the stage from the auditorium, the Lincoln Square Theatre is protected by two fireproof walls, one a three-inch thick steel curtain weighing sixteen thousand pounds, and the other a water curtain.

The steel curtain dropped “by the burning or cutting of a rope.” Even more ingenious was the water curtain, which operated automatically when temperatures rose to 135 degrees. The first of its kind, when activated a sheet of water formed from the sides and top of the proscenium arch. It and the automatic sprinkler system were fed by a 10,000-gallon gravity tank on the roof, and “pressure tanks” that could spew water at a rate of 60 pounds per square inch.

The New-York Tribune described the interior as “Louis XIV,” its general color scheme playing off shades of “old rose.” The mural work throughout the theater was done by Herman H. Rulfs, including three figures over the proscenium—Music, Drama and Poetry. He was also responsible for the “ornamental scroll work here and there about the pillars and on the walls.” Artist Matt Morgan, Jr. decorated the curtain with “a scene in the Orient made from some of Mr. Morgan’s drawings when in India,” according to the article. The Sun described the theater as “a comfortable, sweet and clean appearing place, airy and light in its finishings of white, blue and gold.”

Less than a year after its opening, the West Side Amusement Company realized that legitimate theater was not working.

The theater was capable of seating 1,603 patrons. Its stage was 90 feet wide and 43 feet deep. Managed by the West Side Amusement Company, it opened on October 30, 1906 with Edward Peple’s play, The Love Route.

A month after its opening, the Lincoln Square Theatre played to an impressive audience. Charles Miller, a director of the West Side Amusement Company, was a member of Company D of the Seventh Regiment. To show their support, on the evening of November 30, 1906, the entire regiment attended the performance of The Love Route. The New-York Tribune noted, “The proscenium boxes will be occupied by the officers of the company and will be appropriately decorated with the American Colors. Special patriotic music will be supplied by Giovanni E. Conterno, the conductor of the Lincoln Square Orchestra.”

Less than a year after its opening, the West Side Amusement Company realized that legitimate theater was not working. On May 3, 1907, the New-York Tribune reported that vaudeville manager Charles E. Blaney had leased the theater, noting that Blaney’s staff would move in the following evening. “He also said that he would make it a high-class house,” said the article.

On December 23 that year, Blaney introduced his new musical, The Bad Boy and His Teddy Bears, with music written by Ted Coleman. The New-York Tribune reported, “The purpose is to offer a cheerful and winning Fairy story, in an attractive dress and with a good cast.” The play ran for weeks to what The Philadelphia Inquirer described as “delighted” audiences. An especially delighted and unusual audience sat through a matinee on January 9, 1908, when The Evening World booked the entire theater for 800 deaf and hard-of-hearing school-age children. The following day, the newspaper reported on the successful outing, saying, “Most of the children had never witnessed a stage performance before, and their delight and amazement grew with every new wonder that opened before their dancing eyes.”

Blaney’s Lincoln Square Theatre was, overall, a vaudeville house. The acts on September 5, 1908, included Alexander Carr and Company in The End of the World, which received a dozen curtain calls, according to The Sun, adding, “Miss Emma Carus was also popular.” Also on the bill was Biana Froelich, “lately the premier danseuse of the Metropolitan Opera House,” said the article, who danced the Dance of the Seven Veils. The report noted, “Mlle. Froelich wore fleshings [i.e. flesh-colored tights] and the audience appeared to appreciate the artistic nature of the dance.”

While Biana Froelich’s fleshings were acceptable, Vesta Victoria’s costume two months later was not. Theatres could only hold “concerts” on Sundays. Plays were considered profane on the Sabbath. And so, when the English music hall singer speared in a “ballet skirt” during the Sunday concert on December 6, 1908, she was arrested, along with assistant manager Joseph Folly. She was held in violation “of that section of the city charter which says, in effect, you mustn’t wear fancy costumes or dance a jig when you appear at a ‘sacred concert,’” reported The Evening World.

As it turned out, Victoria and Foly were released because the magistrate was unable to understand the arresting detective’s description of the garment. After repeated tries, Detective Henne said, “It was just twelve inches long, and it—it didn’t fasten on lower down than a short distance under the arms—you know how that is, Judge.” In frustration, the magistrate declared, “No, I don’t. I am no expert on this subject, and if this is all the evidence you have, I discharge both prisoners.”

After repeated disagreements, on April 15, 1909, Charles E. Blaney’s business partner, William Morris, walked out, taking his performers with him. The New York Times reported, “as a result Blaney’s Lincoln Square Theatre will be ‘dark’ next week.” As part of Blaney’s reorganization, he began showing “photo plays.”

On April 29, 1910, 14-year-old Louise Loeffler made plans with two friends to see a movie. Her mother, however, forbade her to do so. Louise’s friends, Bessie Alterschoon and Ida Coughlin, both 14 as well, remembered Mrs. Leoffler’s words verbatim, “Don’t go to the moving picture shows, Louise. I am afraid they will burn up and you will be burned to death.” And so, the three girls promised they would find something else to do, and immediately went to the Lincoln Square Theatre.

Louise tripped on the carpeting and grabbed the brass railing, which gave way.

The girls were on the second balcony when they noticed vacant seats on the first balcony. They scurried in the darkness to get there. Louise tripped on the carpeting and grabbed the brass railing, which gave way. She plummeted headfirst to the orchestra floor to the horror of the theater attendees. The Princeton Daily said, “Several women fainted and the audience was thrown in to an uproar.” Louise died just after midnight at Flower Hospital.

Tragedy was narrowly averted on April 7, 1912. After five men on the second balcony got into a physical altercation, a patron shouted, “Fight!” Many in the audience mistook it as “Fire!” The New-York Tribune reported, “the cry was taken up in all parts of the house. Women with children became excited, and as the house was in darkness, a picture film being shown at the time, it looked as though there would be a general rush for the exits.”

A quick-thinking manager, Charles Fergusen, had the house lights turned on and announced from the stage that there was no fire. The in-house fireman reassured the crowd, and everyone returned to their seats. The New-York Tribune concluded, “In the excitement many Easter hats were damaged, but no person was injured.”

On January 30, 1931, a raging fire tore through the Broadway Arcade, destroying the six-story building and damaging the Lincoln Square Theatre, which had emptied only minutes earlier. The damages, mostly caused by smoke, were repaired, and the Lincoln Square Theatre reopened on September 4, 1931, as the Loew’s Lincoln Square Theatre.

At some point, the Lincoln Square Theatre closed, and the auditorium was converted into a television studio. Then, in 1958, it was demolished with the other buildings on the block to make way for the Julliard School of Music which opened in 1969.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com