141 West 61st Street

by Jessica Larson

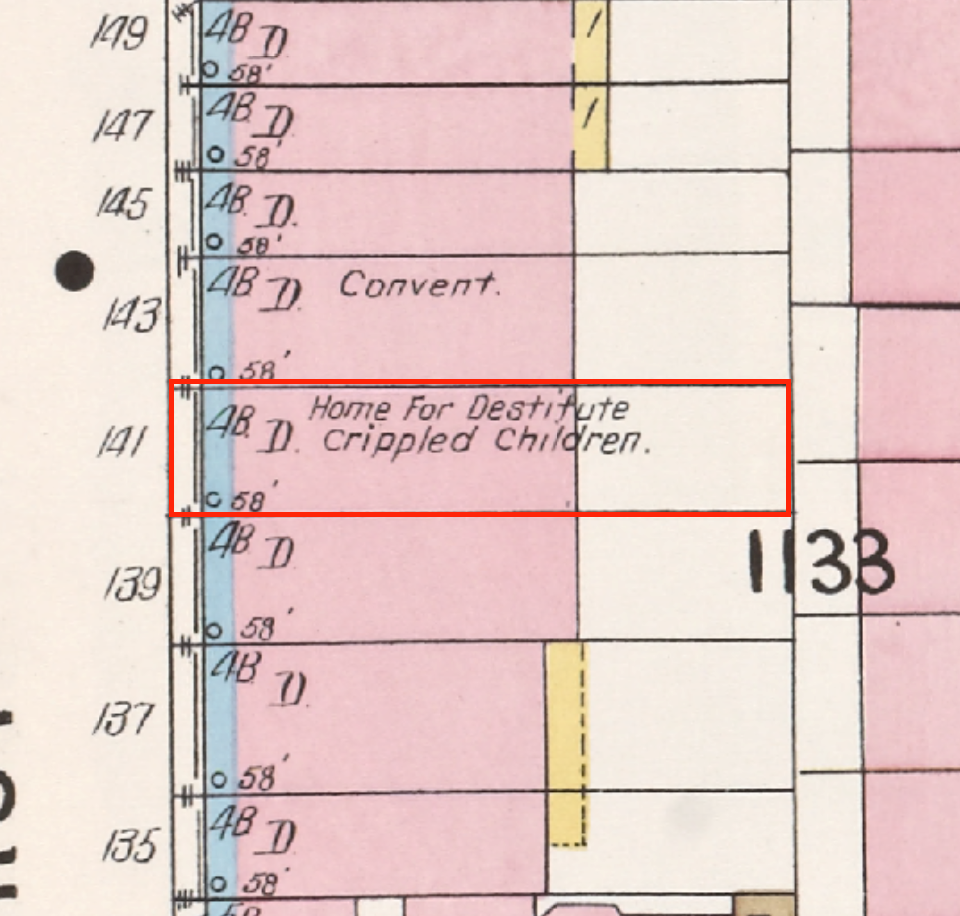

On a site now occupied by Fordham University once previously stood a small charity dedicated to assisting and housing the city’s poorest children. The building was constructed as a four-story dwelling, a brownstone row house in the 1880s. It likely first served as a single-family home and was later converted into a charity, which was a common practice during the Progressive Era. Building and designing purpose-built institutions was costly and charities generally did not have the funds to construct them on a wide scale, plus converting former homes into institutions like children’s shelters helped replicate the sense of a stable, middle-class home. The first recorded childcare institution in the building was the New York Home for Destitute Crippled Children. This opened in 1904 and was funded by a woman named A. Louise Erlanger, full name being Adelaide Louise Balfe Leonard Harcourt Erlanger. Erlanger was an English actress who had, as her long name indicates, married many times – twice in bigamist marriages. The eccentric philanthropist retired from the stage in 1912 to focus on charity work. Interestingly, despite being incorporated, the institution did not receive state or municipal aid (usually, a charity would receive some, even if minimal, aid if incorporated). True to the benefactor’s interests, the institution often raised money by having the children put on theater performances. The workers (or reformers) were not paid, and the institution was non-sectarian, although, in the nineteenth century, this often meant they were broadly Protestant and still enforced certain Protestant teachings.

The New York Home for Destitute Crippled Children brought the children to areas outside the city during the summer months.

San Juan Hill was often noted as having an unusually high rate of disabled children. This led as well to the establishment of a similar institution at 224 West 63rd Street. The institution could house up to 30 children, ages four to fourteen, and allowed them to stay five to six months. Despite these children’s physical disadvantages, reformers at the institution still expected them, as reformers generally expected from all they assisted, to aspire to become self-supporting and free of charitable help. The institution at 141 West 61st Street operated as an “industrial school,” meaning that in addition to sheltering children, they trained them in manual trades that would, or at least as reformers hoped, lead to steady employment. The institution did offer physical exercise classes specifically tailored to children with disabilities.

As was common with such institutions, the New York Home for Destitute Crippled Children brought the children to areas outside the city during the summer months. One location was listed as Patchogue, Long Island, though they later began to summer in Ridgefield, New Jersey. As city life was considered both morally corrupting and bad for children’s physical health, these outings were intended to give poorer children an escape from the detriments of urban living.

In the 1910 Federal Census, the head worker is listed as 29-year-old widow from Scotland, Gean Gordon. Her 11-year-old son also lived in the building with her. 16 children, both male and female though all white, are listed as residing at the address. Surprisingly, all of these children were born in the United States, although many were the children of European immigrants.

In May of 1913, the institution was renamed the A. Louise Erlanger House. This was likely due to their partnership with an organization called the Children’s Aid Society, which likely overtook the operations of the institution. The building continued to serve as a temporary shelter for homeless children, although the focus seems to have shifted away from disabled children. The Children’s Aid Society was a large organization whose legacy is complicated. They pioneered a program called “placing out,” wherein poor children placed in their care were often sent to rural families; the purpose was nominally to offer these children an escape from the detriments of the city, but the result was often that the foster families expected essentially free labor from these children and abuse was common. Further, many children’s parents were not notified of this plan and were never able to establish contact with their children again. This is commonly referred to as the “Orphan Train Movement.”

Available records for the institution begin to taper off in around 1920. The address was not included in either the 1920 or 1930 Federal Censuses. In 1961, the site reopened as Fordham University’s new campus as part of the Lincoln Square Renewal Project.

many children’s parents were not notified of this plan and were never able to establish contact with their children again.

Resources:

1910 United States Federal Census, New York, Borough of Manhattan, Election District 1318, Ward 22, image 20/38. Familysearch.com.

“Benefit for Crippled Children.” New-York Tribune. February 7, 1909: p. 7.

Charity Organization Society. New York Charities Directory. Charity Organization Society of the City of New York. 1909.

“Gossip of the Theaters.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle. December 5, 1904: p. 5.

The People’s University Society Extension of New York. Sixth Annual Report. The People’s University Society Extension of New York. 1904.

“Stage Notes.” Standard Union. April 16, 1906: p. 4.

The State Board of Charities. Annual Report of the State Board of Charities, Vol. 2. J.B. Lyon Company. 1914.

Welfare Commission for Cripples/Federation of Association for Cripples. American Journal of Care for Cripples Vol. 1, no. 1. New York. 1914.

Jessica Larson is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Art History, The Graduate Center, CUNY. She is also the Joe and Wanda Corn Predoctoral Fellow at the Smithsonian American Art Museum & National Museum of American History