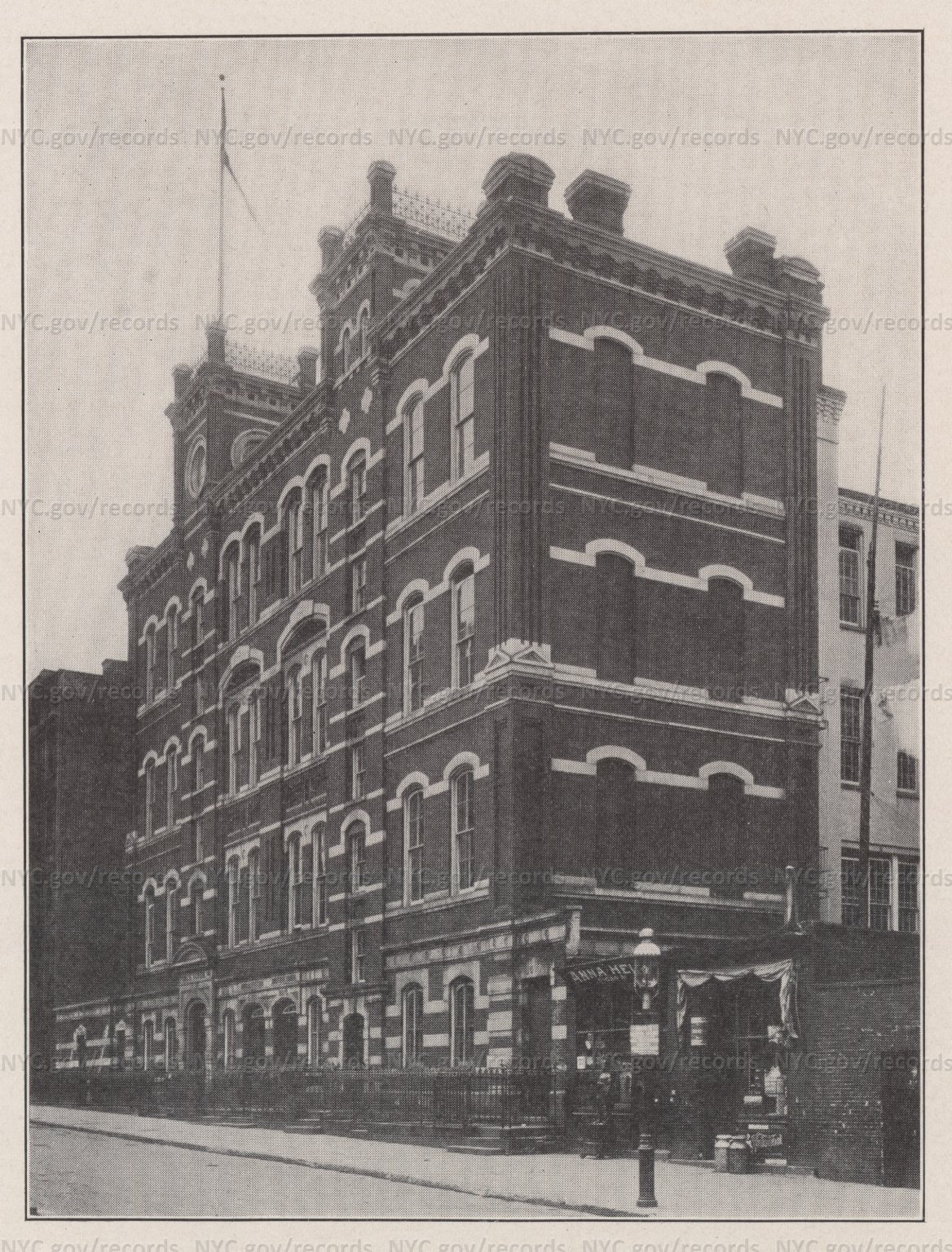

462 West 58th Street – P.S. 141

by Tom Miller

In 1889, two years before he was officially appointed Superintendent of School Buildings, architect Charles B. J. Snyder filed plans for a “five-story and attic brick and stone school” at 462-468 West 58th Street. Faced in red brick and trimmed in limestone, it was a marriage of the Queen Anne and neo-Grec styes. The rapidly developing Upper West Side neighborhood necessitated Snyder’s designing a one-story brick extension six years later.

A large percentage of the students at Public School No. 141 came from the San Juan Hill neighborhood. It was populated by Black and Hispanic families who struggled financially. On July 13, 1897, The World reported that P.S. 141 was one of 10 schools in the city that remained open in the summer months for “vacation school.” The article said the children attended “not because they had to, for this is the vacation season, but because they wanted to. They preferred the comfort, light and air of the school-house to the cramped quarters of their tenement homes.”

A by-product of tenement house living was disease. On August 17, 1911, The Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported that the roof of the Vanderbilt Clinic at 59th Street and Tenth Avenue had been made an “annex to Public School No. 141” to accommodate students with tuberculosis. “These children remain in the open air throughout the day, summer and winter,” said the article. It explained, “they are given fresh eggs and milk several times per day, and a warm and nourishing meal at noon, and they receive medical treatment daily. The instruction is adapted to the needs of each individual, the amount of work being determined largely by the physician in charge.”

children attended “not because they had to, for this is the vacation season, but because they wanted to…”

In 1915, Frances Blascoer held the cumbersome title of Special Investigator for the Committee on Hygiene of School Children of the Public Education Association of the City of New York. That year, she published a study titled Colored School Children in New York. In it, she said that Public School 141, “with 166 colored pupils,” and two other schools had the most Black students in the city. Her findings uncovered rampant racism within the school system. Principals and teachers asserted that “the problem of the colored child” was a result of issues “peculiar to colored people.” Those ranged from “the effect of street life on colored students to the belief that the presence of these children had lowered standards of scholarship and conduct in the schools.”

The problem of fires was addressed in 1922. In May, the school was outfitted with fire alarm boxes. As the student body assembled in the auditorium on May 9 to hear Fireman George Heemsath instruct them on the devices, he explained their workings to Principal Kate A. Walsh. “Now the principal thing to avoid is touching this part right here,” said Heemsath. “If you press that, you send in an alarm.” And then he accidentally set off the alarm.

The Evening World reported, “The next minute, Engine Company No. 28, just off Seventh Avenue in West 58th Street was on its way answering a false alarm from the school. In addition, 1,500 pupils were marching down the stairs in orderly manner and filing out of the building.” The article concluded, “After the excitement was all over, the children were marched back to the auditorium and the fireman explained the new system to the children.”

It was not a false alarm that was sounded on May 14, 1925, however. Sixteen-year-old Nicholas Metexas, a hall monitor, was “making the rounds of the rooms on the second floor collecting the attendance sheets,” according to the Daily News. He entered a classroom that 50 students had just vacated and discovered “a blazing pile of charts which had evidently fallen from the wall of the room after catching fire.”

The boy notified a school employee, who grabbed fire buckets while Nicholas ran to the principal’s office. “The school fire alarm was sounded and the pupils, believing that the gong had rung for a regular fire drill, marched to the street without disorder.” Young Nicholas Metexas was lauded for this “cool-headed and prompt action.”

On the morning of December 8, 1927, a fire was discovered by a teacher under a stairway on the second floor. It was quickly stamped out. Then, the following afternoon, a similar fire was found in the same spot. The Gaffney Ledger reported that it “was also easily extinguished.” It did not take investigators long to find the culprit, 11-year-old Joseph Quailey.

The boy was arrested “on a charge of juvenile delinquency” and admitted he set the fires “to beat my lessons” and “because I didn’t like school.” Police described him as “happy and indifferent as he sat in the station waiting to be turned over to an agent of the Children’s society.”

The charges of juvenile delinquency against one student were dismissed

Far more serious was the blaze that erupted on March 22, 1945. It was discovered in an unoccupied classroom on the fourth floor. The New York Times reported, “More than 250 pupils of P. S. 141 at 462 West Fifty-eighth Street were evacuated from the building in three minutes.” They were taken to the Edwin Gould Foundation for Children at 422 West 58th Street, “where firemen brought their overcoats and caps, which were restored to them by their teachers.” The article noted, “Damages, limited to a rear wing of the school building, was considerable.”

Two 11-year-old boys were arrested in connection with the arson. The charges of juvenile delinquency against one student were dismissed, but the other boy was sent to Bellevue Hospital for mental and physical examinations.

On July 27, 1960, the Board of Estimate sold the “Former Public School 141” at public auction with a minimum opening bid of $225,000. The property was purchased by Yeshiva University, which operated from the building until the summer of 1978. On July 7, The New York Times reported that Yeshiva University “plans to sell” the property.

A renovation completed in 1981, resulted in a total of 41 apartments throughout the former school building. A subsequent remodeling into luxury residences by Alchemy Properties, Inc. was completed in 2009. Now called the Hudson Hill Condominium, no hint of Charles B. J. Snyder’s 1889 façade survives.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com