Amsterdam Houses

by Jessica Larson

In April 1949, the New York City Housing Authorities opened Amsterdam Houses, one of the first postwar public housing projects in Manhattan. This large housing complex offered low-income tenants the possibility of housing stability while maintaining quality architectural solutions to longstanding issues of density and safety.

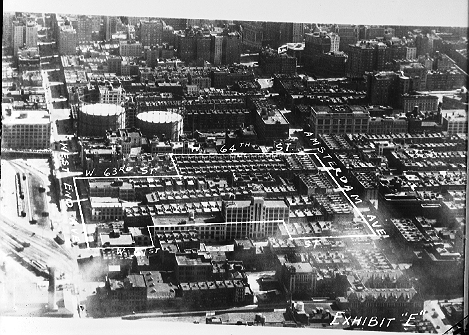

The creation of Amsterdam Houses was announced by mayor Fiorello LaGuardia in 1940. The chosen site, between West 61st and West 64th Streets, Amsterdam and West End Avenues, was formerly the densest area of San Juan Hill, as well as one of the densest in Manhattan for a time. On eight of those lots were the Tuskegee (213-215 West 62nd) and Hampton (210-218 West 63rd) model tenements; these were philanthropically funded structures reserved for low-income Black tenants in the early twentieth century. They were funded by Olivia and Caroline Phelps-Stokes, sisters who had inherited a massive fortune from their family’s real estate and mercantile businesses. Their nephew, Isaac Newton Phelps-Stokes, was a respected architect and deeply invested in social reform; he designed the model tenements and continued to play a significant hand in the development of the city’s public housing design and policy until his death in 1944. This involvement led to the city’s purchase of the model tenements’ lots for redevelopment in 1941.

…more than half of those displaced tenants were relocated to Harlem, generally to haphazardly rehabilitated tenements.

World War II stalled plans for the construction, but demolition of existing structures began in September 1941. Announcing “Farewell to the slums,” the Lincoln Square Tenants League organized a block party to kick off the demolition, attended by LaGuardia and other local political figures. The intent following the war was to offer tenancy in Amsterdam Houses to returning veterans and San Juan Hill residents who had been displaced by the construction, who were largely Black. To this end, the expectation was that the project would be racially integrated, which was mandated by a 1939 law. Ultimately, white veterans were prioritized while prospective Black tenants were often relegated to long waiting lists. This was a significant disappointment to San Juan Hill’s Black residents, who had been assured that their occupancy in the project would be substantial; more than half of those displaced tenants were relocated to Harlem, generally to haphazardly rehabilitated tenements. The buildings were completed on December 17, 1948. Upon the project’s opening, only 23% of tenants were Black and 4% were displaced residents of the area.

The housing development was designed by architects Grosvenor Atterbury, Harvey Wiley Corbett, and Arthur C. Holden. Atterbury was a particularly well-regarded architect of residential structures and had previously designed model tenements in the early twentieth century. The designs of the original Amsterdam Houses structures were similar to contemporary and interwar public housing projects throughout the city; there were a total of 1,084 units with varying floorplans for different family sizes. Against Isaac Newton Phelps-Stokes’s input, most of the buildings were lower rise than the “Towers-in-the-Park” schemes that would come to characterize public housing architecture in the 1960s. The Amsterdam Houses complex shares similar design features, however; the buildings are inward-facing to separate residents from the busy surrounding streets. These interior areas were designed by landscape architects Gilmore D. Clarke and Michael Rapuano and are tree-lined and organized axially, an effort to incorporate green space into the urban environment as well as safer areas for children. Of the original structures, ten were six stories and a basement, with most in the “I” shape reminiscent of the model tenements that were formerly on the lots. These were similar in scale to the city’s tenement buildings, though these new public housing structures did not incorporate commercial spaces and covered far less of the original site. The three cruciform buildings that line Amsterdam Avenue are thirteen stories and a basement, effectively creating a sort of barrier between the primary area of the housing project and the street.

The housing project encompassed more than just residential structures. Again, building off of precedents developed by model tenements, the plan included space for social services such as a nursery, a health clinic, and a community center. Residents were offered classes in topics such as proper childcare and money management. The nursery was a branch created by the Masters Nursery of 210 West 64th Street, which had been in San Juan Hill for 60 years.

As part of the phenomenon of “white flight” in the late 1950s and 1960s, wherein white city residents relocated to suburbs or exurbs en masse, Black and Latino tenants began to replace white tenants in Amsterdam Houses. With the construction of Lincoln Center and commercial and market-rate development of the area, Amsterdam Houses became disjointed from its quickly gentrifying surroundings. Amsterdam Houses is not unique in this regard; numerous NYCHA projects throughout the city have been increasingly plagued by the problem that their residents are not financially compatible with their neighborhoods, making it difficult to truly take part in the social lives of their communities. Tenants have continued to push for improved conditions and building maintenance, however–efforts that have sometimes proved fruitful, such as a recent announcement of secured funding to rehabilitate one of the complex’s playgrounds.

Residents were offered classes in topics such as proper childcare and money management.

Resources:

“Applications for New Housing Projects Open.” The Tablet. November 08, 1947:p. 3

Bloom, Nicholas Dagen. Public Housing That Worked: New York in the Twentieth Century. University of Pennsylvania Press. 2014.

“Farewell to the Slums.” New York Times. October 6, 1941: p. 19.

Gardner, Deborah S. “Practical Philanthropy: The Phelps-Stokes Fund and Housing.” Prospects 15 (1990): 359-411.

“Housing Authority Buys 2 Tenements.” New York Times. August 15, 1941: p. 30.

“The Neighborhood Ties That Still Bind.” New York Times. August 2, 2004: p. 4.

“New City Statutes Set for Pioneer Nursery.” New York Times. February 1, 1949: p. 4.

Pennoyer, Peter and Anne Walker. The Architecture of Grosvenor Atterbury. W.W. Norton. 2009.

“Plans Filed by the City For Amsterdam Houses.” New York Times. July 27, 1946: p. 32.

Schwartz, Joel. The New York Approach: Robert Moses, Urban Liberals, and Redevelopment of the Inner City. Ohio State University Press. 1993.

“What Other Editors Say.” The New York Age. August 04, 1945: p. 6.

Jessica Larson is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Art History, The Graduate Center, CUNY. She is also the Joe and Wanda Corn Predoctoral Fellow at the Smithsonian American Art Museum & National Museum of American History