High School of Commerce

by Tom Miller

On July 1, 1890, 30-year-old Charles B. J. Snyder was appointed Superintendent of School Buildings of the Board of Education. Among his responsibilities was to design the new buildings, and before his retirement in 1923, he designed more than 700 school structures within the five boroughs. One of them, the High School of Commerce, designed in 1900, was especially noteworthy–both for its architecture and its ground-breaking educational concept.

A few years earlier, the Chamber of Commerce and Columbia University conceived of a high school that would prepare boys for positions in commerce, a sort of trade school for businessmen. At the cornerstone laying ceremony on December 14, 1901, Board of Education President Miles M. O’Brien said in part, “This school…is the pioneer high school of commerce in New-York, or in the country, and it owes its creation to the fact that the United States has become the leading commercial nation in the export of its products, even Britain now being second.”

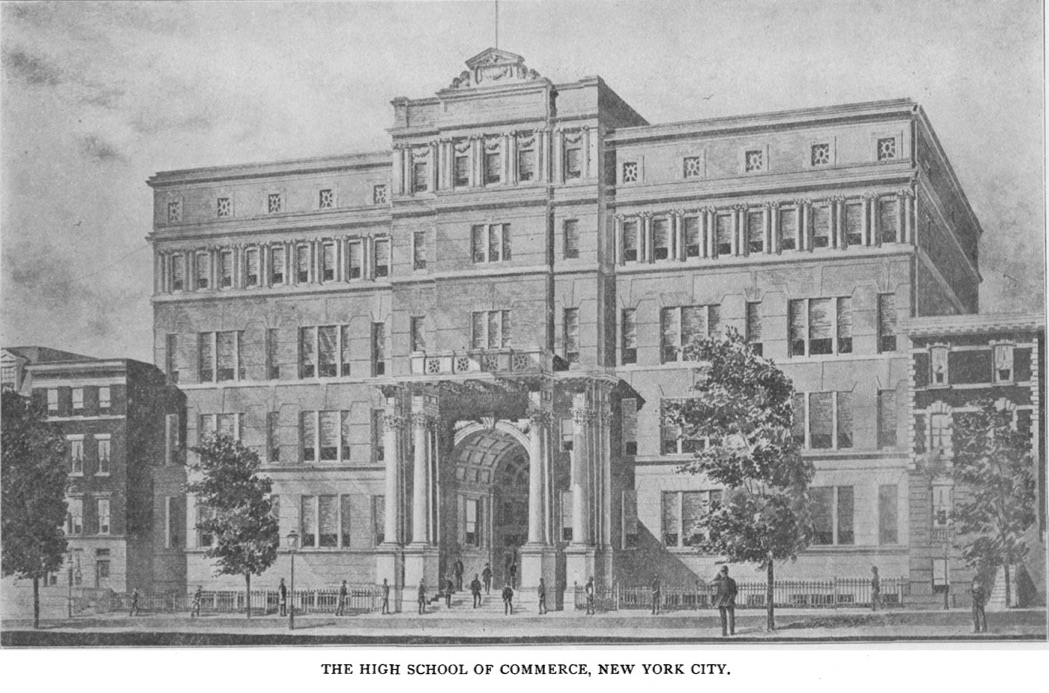

The construction site stretched through the block from West 65th to West 66th Street, between Amsterdam Avenue and Broadway. Snyder’s plans projected the construction costs at $302,640—more than $9.6 million today. His striking brick-and-limestone clad structure would rise five stories above a basement level. He lavished the generally Renaissance Revival design with grand neo-Classical elements—paired, engaged Corinthian columns at the fourth and fifth floors, pierced Roman-style openings on the fifth floor that matched the openwork railing of the third-floor balcony, and a temple-like parapet. But most dazzling was the 65th Street entrance, designed like a grand triumphal arch recessed into the building.

The High School of Commerce was completed in 1902. The five-year curriculum was “broad and liberal,” according to officials. The courses required for freshmen, for example, were English; a choice of German, French or Spanish; Algebra; Biology (“with special reference to materials of commerce”); Greek and Roman history; Stenography; Drawing and penmanship; Physical training; and music. First-year students were also required to have a least one hour of “exercises in voice-training and declamation” per week.

Board of Education President Miles M. O’Brien said in part, “This school…is the pioneer high school of commerce in New-York, or in the country, and it owes its creation to the fact that the United States has become the leading commercial nation in the export of its products, even Britain now being second.”

A 16-year-old student, Ralph Cooper, wrote a detailed description to induce other boys to enroll. Published in the New-York Tribune on May 30, 1909, it read:

Dear Little Men and Little Women: I would like to tell you about the High School of Commerce, the school to which I go. This school is situated at 65th street, between Broadway and Tenth avenue. Only boys attend this school.

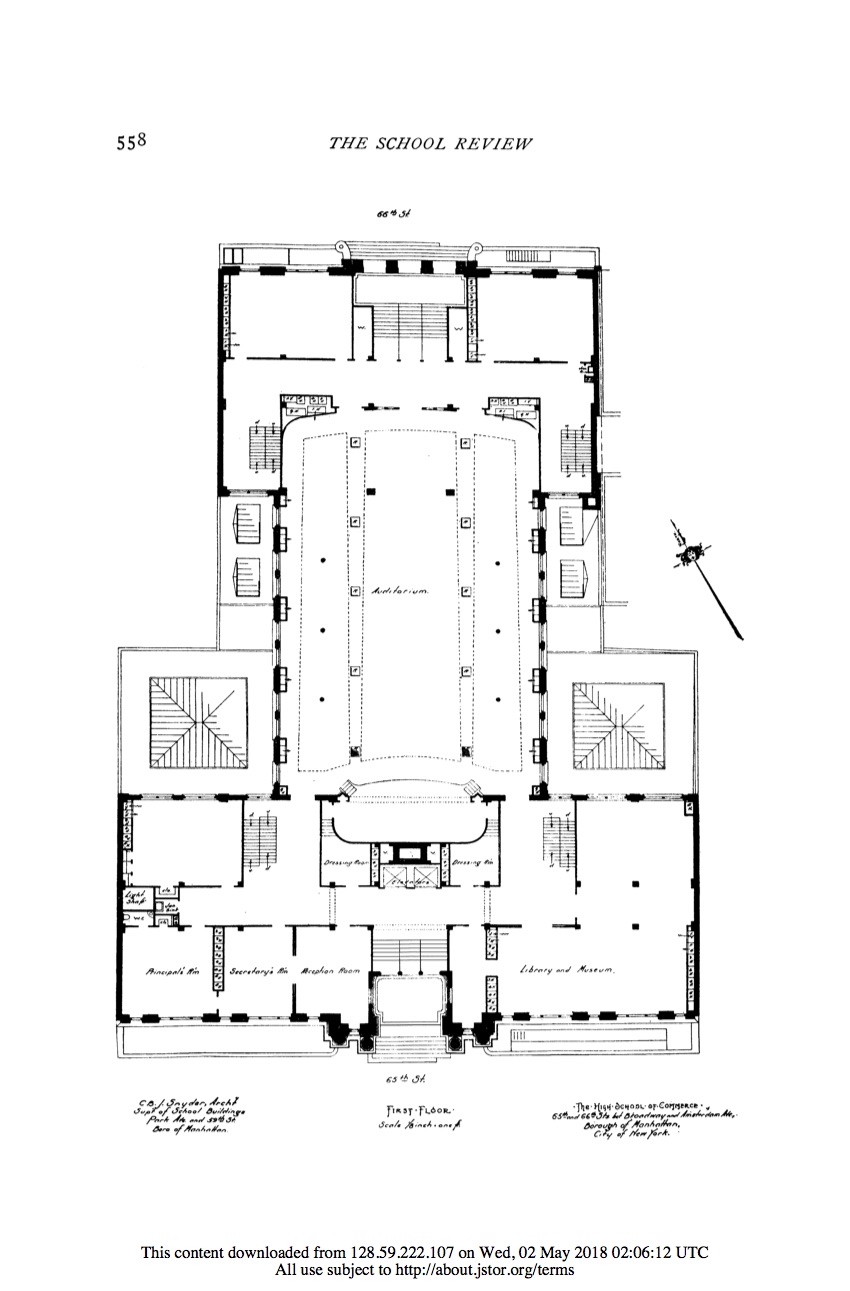

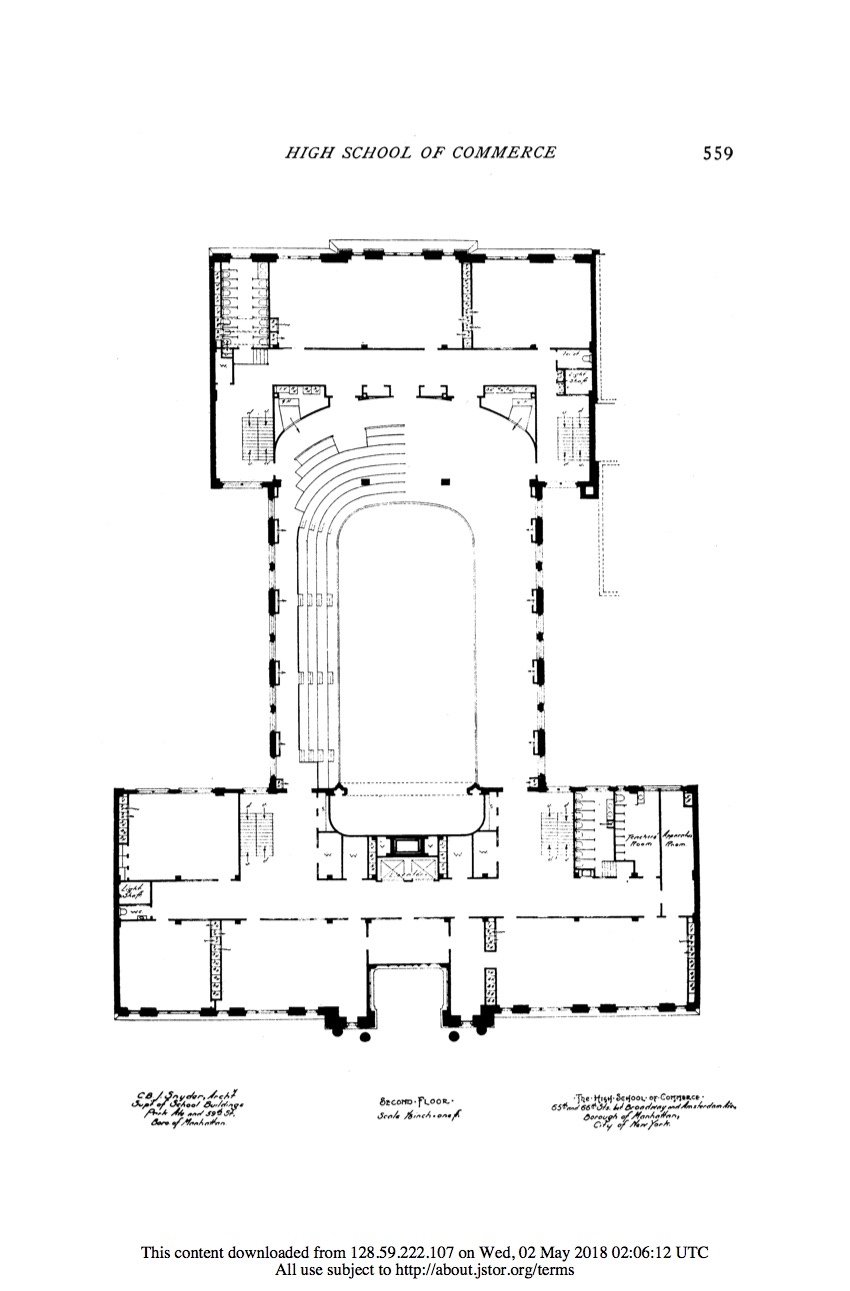

In the basement there is a swimming pool and a gymnasium. The first floor contains several classrooms, an auditorium, seating 1,500 boys, and the principal’s office. The other four stories are made up of classrooms and laboratories.

There are many boy organizations in “Commerce.” Literary societies, chemistry and camera clubs and others. Seventy teachers make up the faculty.

On Friday afternoons there are interesting assemblies, and often prominent men speak. Sometimes plays and debates are given to interest the students.

Boys who wish to get a good business training should by all means go to the High School of Commerce.

Many graduates went on to impressive careers, like architect Lewis Ross. He was employed by Ewing & Chappell in 1916 when he was awarded fourth prize in The Sun’s Country Home Competition for “plans and a design of a dwelling that can be erected for a sum not to exceed $4,500.”

Athletics played a significant role in the students’ lives, and achievements in baseball, track, football, soccer, basketball, and other sports were widely followed in the newspapers. One of its most active athletes in the post-World War I years was Henry Louis Gehrig, who was on the football, soccer, and basement teams. In 1920 the Commerce team traveled to Chicago for a national baseball championship game. There former President William Howard Taft stopped by to wish the team well. On June 26, in the ninth inning of the game in Wrigley Field, Gehrig hit a grand slam home run—only the 19th ever hit in the ballpark.

Seven years later, Lou Gehrig was a sports phenomenon. On June 27, 1927, he was invited to award letters to the Commerce athletes and to referee the school track meet. He had no idea what he was headed for. The New York Times reported, “Lou Gehrig was rushed at Pelham Bay Park yesterday afternoon. The star first baseman of the New York Yankees had this experience when 2,500 youngsters from the High School of Commerce rushed him at the annual field day of the school.” The famous graduate somehow managed to perform his duties and sign scores of autographs and baseballs.

A peculiar incident happened on January 17, 1929. The New York Times began an article saying, “The lives of more than 1,000 pupils at the High School of Commerce…were endangered yesterday afternoon when three fires of incendiary origin started in different parts of the school within half an hour.” At the time, midyear examinations were in progress.

The first blaze was discovered around 2:30 in the gymnasium on the fifth floor. A physical education teacher, Samuel Prenn, walked into the room and found a wastepaper container on fire. He and an assistant custodian put it out with a fire extinguisher, then reported it to the principal. Ten minutes later, a janitor discovered a pile of trash on fire in a washroom on the first floor. He, too, was able to put it out with a fire extinguisher. Then, swimming instructor Hugh Jones noticed smoke coming through a transom of a ground floor classroom. The New York Times said, “He broke open the door, found the room unoccupied, and the wastebasket under the teacher’s desk in the middle of the room in flames.” While he was able to put it out, the desk was heavily burned and, had the fire not been discovered when it was, would have caused much damage.

One of its most active athletes in the post-World War I years was Henry Louis Gehrig, who was on the football, soccer, and basement teams.

Lou Gehrig died of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, often referred to as Lou Gehrig’s disease, on June 2, 1941, just before his 38th birthday. In tribute, two years later, in November 1943, the High School of Commerce students launched a fund-raising drive. Within two months, they had raised the equivalent of $30,000 today to purchase an ambulance as a gift to the United States Army.

At a ceremony in the school auditorium on January 25, 1944, Lieutenant Marcella R. Meyer of the WAC, accepted the fully equipped army field ambulance called “The Spirit of Lou Gehrig.” In her remarks, she said, “The gift of this ambulance is a manifestation of the spirit of a man who was loved by everybody.” Gehrig’s widow then asked the assembled students to say a prayer “for the boys who will be transported in this ambulance.”

A substantial “annex” was erected in 1930 that essentially doubled the size of the facility. Three decades later, it looked as if the school would be enlarged again. As much of the old San Juan Hill neighborhood was being demolished for the Lincoln Square redevelopment project, The New York Times reported on April 20, 1961, that only two tenement buildings still stood on the block with the school. “The city wants to tear down the two remaining tenement buildings to extend the High School of Commerce,” said the article.

But the city changed its mind. In 1964 demolition of the High School of Commerce was scheduled. Ironically, a protest letter to the New York Times editor did not seek to preserve Charles B. J. Snyder’s magnificent Roman-inspired structure, but the more industrial 1930 addition. “It is little more than thirty years old and with slight renovations would be in excellent shape,” said the writer. “Why tear this wing down?”

In the end, nothing was preserved. Today Lincoln Center’s Samuel B. and David Rose Building, and portions of the Juilliard School sit on the site.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com