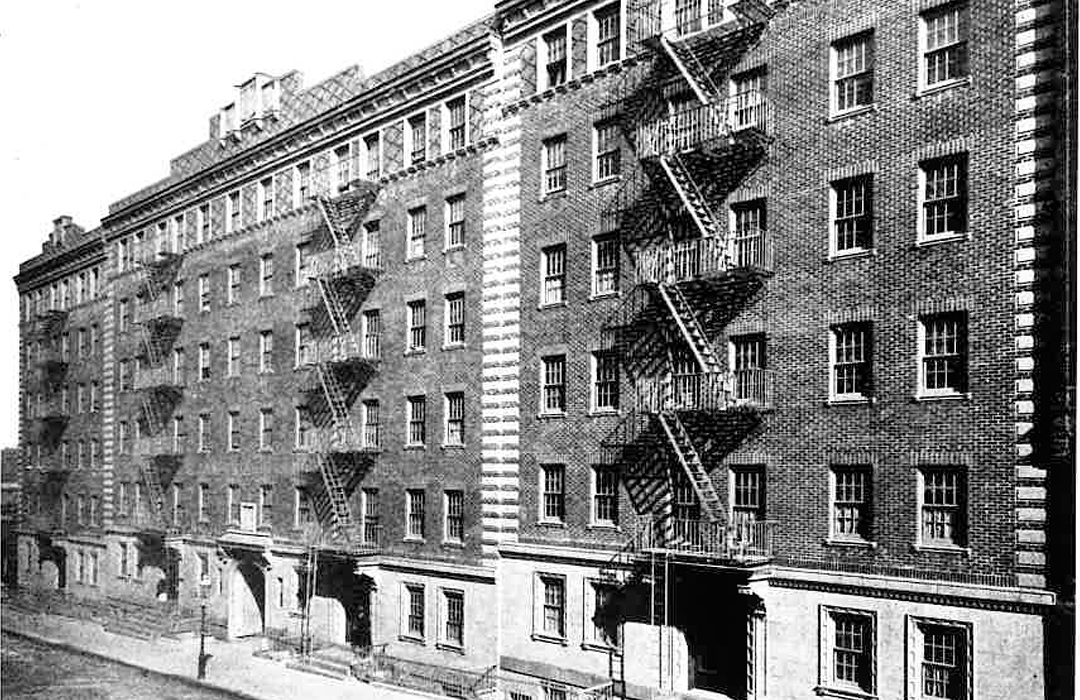

View of 231-245 West 63rd Street from south. Image by NYC Housing Authority Courtesy Office for Metropolitan History.

Phipps Houses No. 2

by Jessica Larson

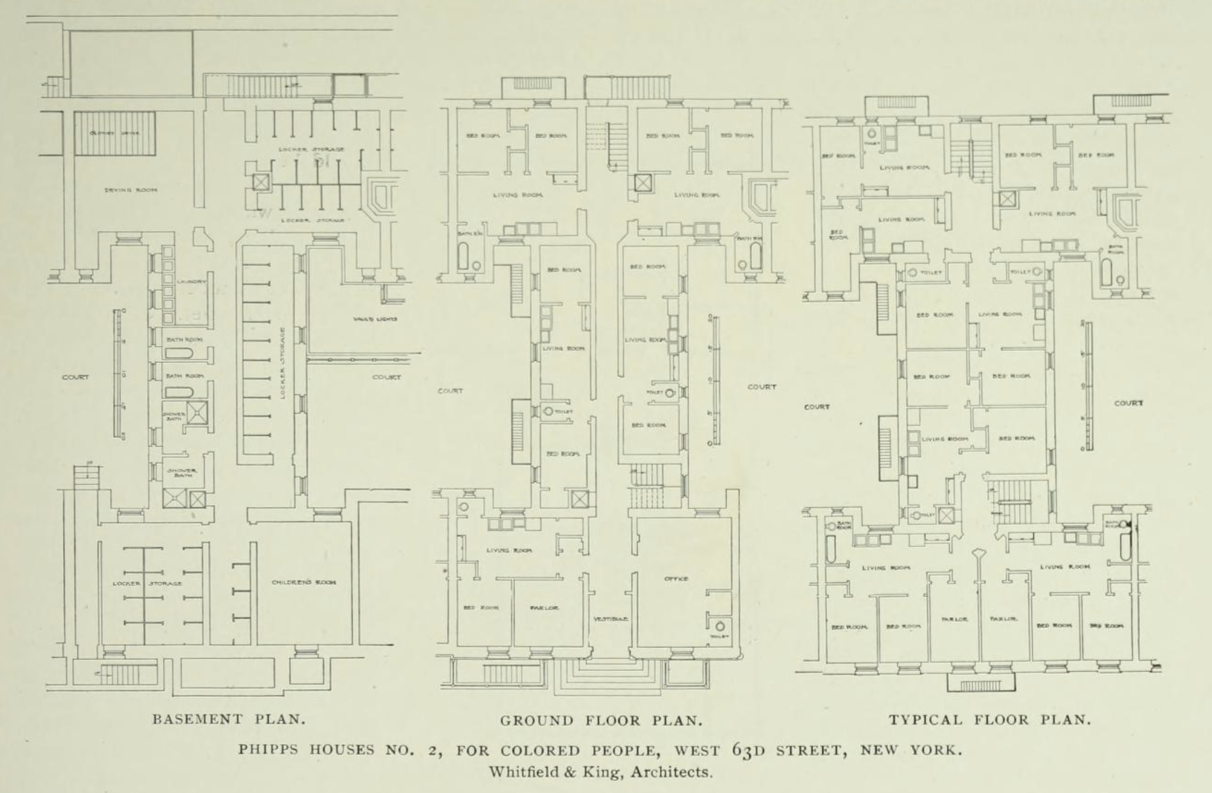

Built in 1906, Phipps Houses No. 2 (sometimes referred to as “Phipps Model Tenements No. 2”) was the second of the four model tenements built for Black tenants in San Juan Hill and, ultimately, the most well-known. Out of these four, Phipps Houses No. 2 and Phipps Houses No. 3, (sited on the lots directly behind Phipps Houses No. 2 on West 64th Street), are the only two that were not destroyed and redeveloped in the 1930s for NYCHA’s Amsterdam Houses. Originally, this structure consisted of 164 apartments, with 2-bedroom, 3-bedroom, and 4-bedroom options. In keeping with modern standards, as well as increasingly strict housing legislation, the building was fireproofed and equipped with steam heat, hot water, and private bathrooms.

Following the success of the Tuskegee Model Tenement (213-5 West 62nd St.), which proved quickly to turn a modest profit for its investors, interest grew amongst Progressive reformers and philanthropists to provide affordable, quality housing to the city’s growing Black population. These structures incorporated the latest innovations and legislation regarding housing design, which included large central courtyards for better lighting, air circulation, and fire prevention, as well as units better designed around accommodating the nuclear family structure. These model tenements were the result of complex motivations –while many reformers were sincere in their desires to assist Manhattan’s Black poor, many also saw a financial opportunity, and a means to control the ways in which Black residents lived. Ultimately, model tenements were criticized for still being too inaccessible for the poorest of the poor – like criticisms later leveled against NYCHA, these housing developments were more geared towards those who were already upwardly mobile –and gradually became populated by the middle-class.

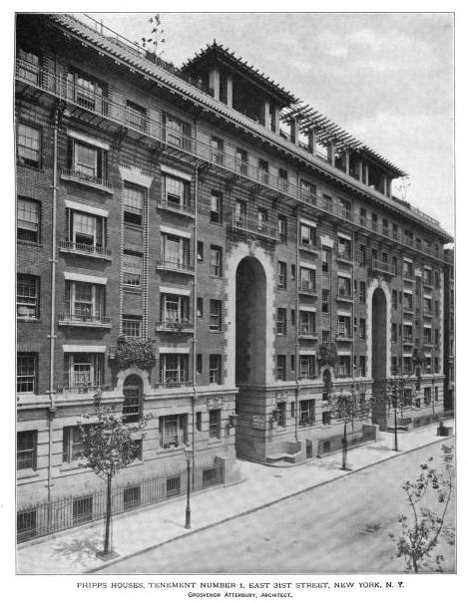

The philanthropist behind Phipps Houses No. 2 and 3 was Henry Phipps Jr., a business partner of Andrew Carnegie. Just prior to the opening of Phipps Houses No 2, Phipps had funded the construction of Phipps Houses No. 1 (321-337 East 31st St., no longer standing); designed by noted residential housing architect Grosvenor Atterbury, this model tenement was intended to house white immigrants, mostly Germans. In many ways, Phipps Houses No. 1 reflected spatial and reform choices that were echoed in the design of Phipps Houses No. 2, though the one built for white tenants was more well-funded and offered additional amenities, including an ornate rooftop garden, mostly used as a children’s learning and play space, and a chapel. Phipps Houses No. 2, comparatively, was more conventional in its interior design and facade, likely as a cost-cutting measure.

Phipps Houses No. 1 was “much better than the second one for the Negroes”

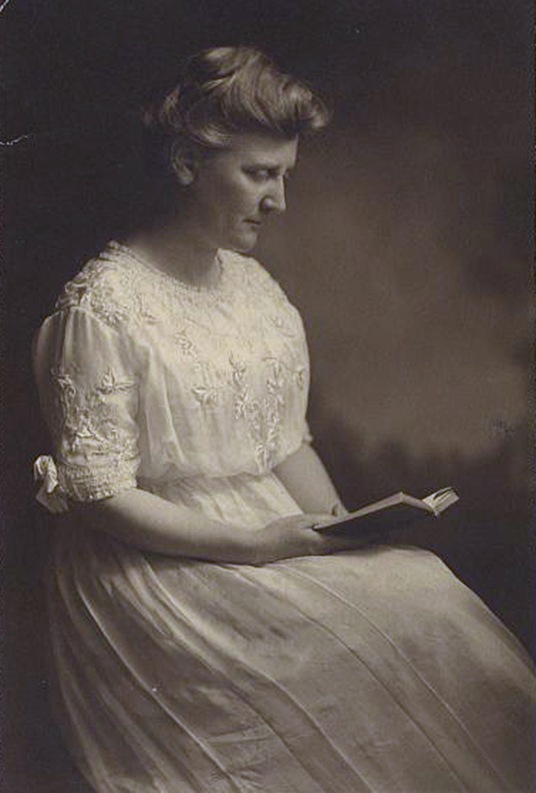

Phipps was persuaded to construct housing in San Juan Hill for Black tenants by Mary White Ovington and John E. Milholland, both white reformers who would later be instrumental in the founding of the NAACP in 1915. Ovington, who had been active in the settlement house movement in Manhattan and Brooklyn, pushed for the inclusion of spaces for reform work within Phipps Houses No. 2 while Milholland, a wealthy businessman who had made his fortune in pneumatic tubes, provided sound financial advice. Ovington sought to incorporate the spirit of settlement houses into the improved and updated architectural space of model tenements; rather than occupy a Victorian mansion in the vein of a “big boarding house,” as was customary of settlement work, Ovington proposed to “get a model tenement built in one of the crowded Negro quarters, preferably the Sixties, and to have room in it for settlement work.” W.E.B. Du Bois, whom Ovington was in regular contact with regarding these plans, had publicly pitched this concept at a conference in 1903 held at Mount Olivet Baptist Church on West 53rd Street. Du Bois envisioned this work as a partnership between white and Black reformers, wherein white reformers could guide Black migrants through the inner workings of Northern urban life.

It came as a bitter disappointment for Ovington when the plans for Phipps Houses No. 2 were ultimately sparser and more austere than those of Phipps Houses No. 1. While Atterbury had, by 1906, already begun to make a name for himself in housing design (as well, he designed Phipp’s mansion at 6 East 87th St.), the architects attached to Phipps Houses No. 2, Whitfield & King, were primarily commissioned to design Carnegie Libraries –Henry Davis Whitfield was the brother-in-law of Carnegie, which is possibly how Phipps came to employ him for the San Juan Hill model tenements. In a letter written to Du Bois on December 18, 1905, Ovington communicated that the plans for the model tenement had been finalized and that Phipps Houses No. 1 was “much better than the second one for the Negroes” and that it “did seem hard luck that we couldn’t have come in first.”

Ovington’s vision for the model tenement as a place wherein the boundaries between social and private life were porous, and reformers lived side-by-side with those they assisted, was influential in the planning and use of Phipps Houses No. 2. Ovington proposed that two white women reformers live together in one of the building’s units and two Black women reformers share another, with the rest of the building still reserved for Black tenants. Many of Ovington’s proposals were shaped by interracial reform strategies already active in San Juan Hill, including the New York Free Kindergarten Association for Colored Children (NYFKACC) (for more, see the post for ‘202 West 63rd Street’), a childcare institution staffed and led by both Black and white women. In dialogue and partnership with this association, Ovington liaised with the model tenement’s planners to have two apartment units on the ground floor reserved by the NYFKACC for kindergarten activities and cooking instruction, as well as the use of a childcare room in the basement.

Ovington herself rented one of the reserved apartments for 8 months –she frequently publicized herself as the only white person to live in the San Juan Hill model tenements, though the 1910 census indicates that several white women lived with their Black husbands in Phipps Houses No. 2. While a central figure in efforts to promote racial progress, Ovington was strategic in her self-promotion and likely downplayed the significance of Black organizations and figures to housing reform in San Juan Hill.

Phipps Houses No. 2 remained an important fixture of San Juan Hill for decades – musician Thelonious Monk lived in one of the building’s three-room apartments as a child. At various times, tenants lobbied for better conditions and housing standards equal to the city’s white tenants; for example, in 1917, during a particularly cold winter, tenants at the four San Juan Hill model tenements were denied heat while the white tenants at Phipps Houses No. 1 were not. Black tenants, with the help of Union Baptist Church’s Reverend George Sims (see post for 204-206 W. 63rd St.), organized to pressure the tenements’ owners, the City and Suburban Homes Company, to issue refunds for heating bills. Though the neighboring model tenements “The Tuskegee” and “The Hampton” were destroyed in the 1930s to make way for the Amsterdam Houses, Phipps Houses. No. 2 and 3 were sold in 1961 to private corporations to be used as conventional rental apartments. Recent owners have added two floors, as well as glass canopies over exterior entrances.

[Mary White] Ovington herself rented one of the reserved apartments for 8 months –she frequently publicized herself as the only white person to live in the San Juan Hill model tenements…

Resources:

“Gardens in the Air Where Children Flourish with the Flowers.” The Craftsman: An Illustrated Monthly Magazine, vol. 17, no. 3. December, 1909: 253-257. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=gri.ark:/13960/t6743vn6w&view=1up&seq=279&skin=2021

George B. Ford, “The Housing Problem –III,” The Brickbuilder, Vol. 18 (Jan.-Dec. 1909): 101.

https://archive.org/details/brickbuild18unse/page/n255/mode/2up

“Heatless Apartments are Cause of Heated Argument.” New York Age. December 22, 1917: p. 1.

“Homes for the Working Classes.” The Construction News, Vol. 22, Issue 14. October 6, 1906: p. 283.

“Millionaire’s Effort to Improve Housing for the Poor.” New York Times. November 23, 2003: p. 7.

Osofsky, Gilbert. Harlem, the Making of a Ghetto: Negro New York, 1890-1930. Pennsylvania State University. 1968.

Ovington, Mary White. Black and White Sat Down Together: The Reminiscences of an NAACP Founder, ed. Ralph E. Luker. The Feminist Press at the City University of New York. 1995.

“The Phipps Houses in New York,” The Review of Reviews, Vol. 33 (1906): 316.

Pennoyer, Peter, and Anne Walker. The Architecture of Grosvenor Atterbury. W.W. Norton & Company. 2009.

Robin D.G. Kelley. Thelonious Monk: The Life and Times of an American Original. Free Press. 2009.

Rowan, Jamin Creed. The Sociable City: An American Intellectual Tradition. University of Pennsylvania Press. 2017.

Samuel Zipp. Manhattan Projects: The Rise and Fall of Urban Renewal in Cold War New York. Oxford University Press. 2010.

W.E.B. Du Bois Papers, 1803-1999. Robert S. Cox Special Collections and University Archives Research Center, University of Massachusetts Amherst. https://credo.library.umass.edu/view/collection/mums312

Jessica Larson is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Art History, The Graduate Center, CUNY. She is also the Joe and Wanda Corn Predoctoral Fellow at the Smithsonian American Art Museum & National Museum of American History