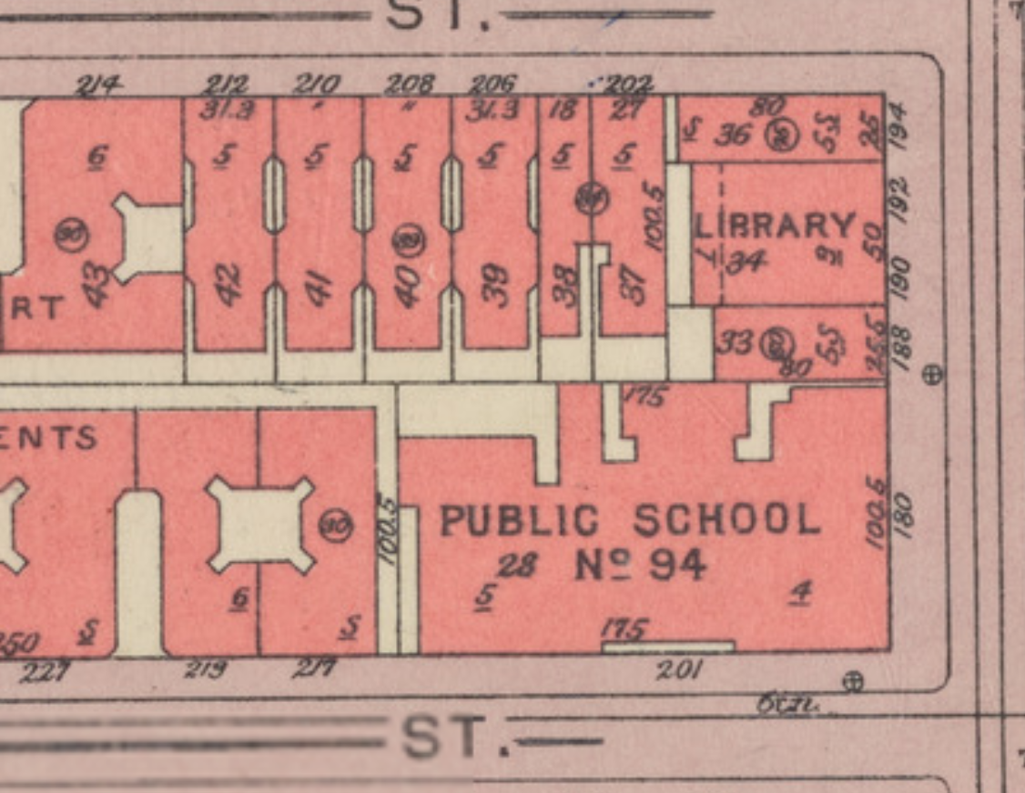

PS 94: 180 Amsterdam Avenue/201 West 68th Street

by Jessica Larson

Built in 1891, this large grammar school served children of the Upper West Side until the mid twentieth century. Emblematic of late nineteenth-century trends in the city’s public school design, PS 94’s student body witnessed the area’s ever changing demographics as new immigrant groups arrived.

New York City was one of the last major American cities to fully establish free public education. Policy had long been mired in debates over religious education, particularly regarding the place of Catholic education, which had complicated funding allocation. Most middle-class or wealthy families simply hired private tutors for their children. Like other social welfare initiatives in the early nineteenth century, privately-run and financed organizations led the charge to expand services to the poor. The New York State Board of Education was formed in 1842, with a taxpayer funded, free public school system codified in 1851. By the end of the nineteenth century, full-time education was compulsory for children ages 8 to 12, and children ages 13-14 were only required to attend 80 days out of the year if they were employed. By the 1890s, when P.S 94 was active, truancy laws had become stronger and were more consistently enforced.

The building’s facade followed the Beaux-Arts style, which the state’s Board of Education favored because of its ease of maintenance and easy standardization.

The school’s large, four-story-and-basement building was constructed when the neighborhood was just gaining momentum. The building was brick with limestone trim. The early subway system had expanded uptown shortly before, bringing with it city residents looking for cheaper, less crowded conditions. Still, when the school was built it was the only building on the northside of the block on West 68th Street, save for an old frame structure. By 1896, the building was not large enough to accommodate the growing demand, however; a neighboring Baptist church was temporarily used as an annex for the school until it could be expanded. The new addition was five stories and a basement. The first floor was devoted to a playroom, the second through fourth floors used for classrooms, and the fifth floor outfitted with space for manual training. When first constructed, the school did not have a dedicated playground either indoors or outdoors (in the nineteenth century, playgrounds were often inside school buildings). Instead, the children of PS 94 used empty lots adjoining the school as playspace. The building was later expanded to include a rear lot for playspace. The school was built right when New York City’s new Superintendent of School Buildings, Charles B.J. Snyder, began to institute changes to how schools were designed; based upon European trends, public schools began to be built more commonly on mid-block lots in “U” or “H” shapes so as to include more space for outdoor activities on either street-facing side. Thus, PS 94, situated on corner lots, was soon outmoded. It is possible that, because PS 94 had relatively little outdoor space, activities were conducted on the rooftop –a common solution to lack of space. The building’s facade followed the Beaux-Arts style, which the state’s Board of Education favored because of its ease of maintenance and easy standardization.

Students in the NYC public school system generally followed a well-rounded curriculum, learning English, drawing, music, often either French or German, and other subjects. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it became common for schools to also offer training in manual trades, such as carpentry and cobblering for boys, or sewing and cooking for girls. Also in line with contemporary practices, the girls and boys had separate entrances. Girls entered on Amsterdam Ave, boys entered on West 68th Street. Girls had a separate set of faculty than boys as well, and then a “primary” principal headed the entire school.

As an example of who these figures were: from 1899 to 1913 this primary principal was Cordelia S. Kilmer. She lived just a few blocks west at 32 West 68th Street. Often, teachers commuted long distances –other faculty members are listed as living as far away as Sheepshead Bay and Pleasantville. Most teachers at the school were women, though male teachers were employed as well.

The school escaped initial demolition under the Lincoln Square Renewal Project, which began in 1955

Though a complex history and one that fluctuated as legislation repeatedly changed, New York public schools had essentially been racially integrated since the creation of the system. Like other schools in San Juan Hill, PS 94 was racially integrated. Students and parents at other schools in the neighborhood voiced frequent concerns over their childrens’ treatment by both white teachers and students. While most Black residents of San Juan Hill lived south of West 66th Street, there were certainly Black students who would have attended PS 94. In 1900, the area immediately surrounding the school was overwhelmingly white, mostly middle-class status; men held jobs such as clerks, engineers, or lawyers. Many were European immigrants, with large numbers from Germany and Ireland. By 1910, these demographics had, remarkably, remained relatively consistent. Whereas San Juan Hill just south of the school had become largely dominated by Black immigrants from the West Indies, as well as Black migrants from the South, the upper West 60s continued to be predominantly white European immigrants or their children, with stable financial status. Even by the 1950 Federal Census, the residents directly surrounding the school were still predominantly white, though the school district was large enough to encompass Puerto Rican and Black students living just south.

The school escaped initial demolition under the Lincoln Square Renewal Project, which began in 1955. An image of it can be seen in the background of a scene in West Side Story. In 1970, the site was replaced by the Lincoln Square Synagogue, a large, modern, travertine structure designed by architects Hausman & Rosenberg. The area gained a new school complex, however, with Martin Luther King Jr. High School and Fiorello LaGuardia High School of the Performing Arts.

Resources:

1900 United States Federal Census, New York, Borough of Manhattan Enumeration District 459, Election District 14, Ward 19, image 33/36. Familysearch.com.

1910 United States Federal Census, New York, Borough of Manhattan, Election District 1379, Ward 22, image 12/31. Familysearch.com.

Board of Education of the City of New York. Directory of Teachers in the Public Schools. New York. 1903.

The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, Vol. XLVIII (New York: 1894): 659.

Dunlap, David W. From Abyssinian to Zion: A Guide to Manhattan’s Houses of Worship. Columbia University Press. 2004.

King, Moses. King’s Handbook of New York City. New York. 1892.

National Education Association of the United States. Proceedings of the Department of Superintendence. Chicago, IL. 1902.

NYC School Construction Authority. New York City’s Historic Schools: A History and Guide to Rehabilitation. New York. Publication date unknown.

New York Board of Estimate and Appointment. Proceedings. New York. 1897.

“Miss Cordelia S. Kilmer.” New-York Tribune. Dec. 5, 1900: p. 5.

Salwen, Peter. Upper West Side Story: A History and Guide. Abbeville Press. 1989.

School: Devoted to the Public Schools and Educational Interests, Vol. VIII, no. 1 (New York: Sept. 10, 1896): 355

Jessica Larson is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Art History, The Graduate Center, CUNY. She is also the Joe and Wanda Corn Predoctoral Fellow at the Smithsonian American Art Museum & National Museum of American History