St. Matthew and St. Timothy

26 West 84th Street

by LANDMARK WEST!

In 1967, the Rev. James A. Gusweller opened the doors to a new, million-dollar, Modern structure designed by Connecticut-based architect Victor Christ-Janer, which unified the blockfront from 26 to 32 West 84th Street with a community center (“The Center”) that itself opened in January of 1963. To understand and appreciate the fireproof, reinforced concrete construction, it is important to understand the lineage of the congregation and its place in time, specifically on the Upper West Side.

The Episcopal St. Matthew and St. Timothy church draws deep roots in New York City. First incorporated on Tuesday, March 13, 1810, as the Zion Protestant Episcopal Church, its earliest parishioners initially worshiped at Trinity Lutheran Church on Broadway and Rector Streets. Despite a congregation of both Dutch and German faithful, services were exclusively held in Dutch (even though eight times as many parishioners were German by 1749). The lack of accommodation bred understandable resentment. German parishioners sought German services and were willing to compromise at “every other” sermon but they were unsuccessful and thus separated to establish Christ Evangelical Lutheran Church, making their home in an adaptively reused Benson brewery on Cliff Street, which served them for 18 years.

Colloquially recognized as the “Old Swamp Church,” they continued there until 1794 when a familiar conflict of language erupted. The descendants of the German parishioners largely spoke English and, understandably, sought English services. They went so far as to invite an English-speaking officiant, but within three years, this faction built their own church on Pearl Street. Failing recognition by the Lutheran Consistory, who claim “it is never the practice in an Evangelical Consistory to sanction any kind of Schism…[we] will never acknowledge a new erected Lutheran Church merely English…” [1] The English-language group dug in and even inducted Dr. George Strebeck as their minister. English-language services brought them more followers and moved them to the corner of modern-day Mott and Park Streets to a $17,000 Georgian Gothic Style stone church for the newly named The English Lutheran Church Zion parish. Strebeck failed in attempts to transition the congregation to the Episcopal church and eventually left the parish and New York City, returning years later as rector of St. Stephen’s Protestant Episcopal Church on Broome and Chrystie Streets.

Although not his direct intent, his return lured away families from the English Lutheran Church Zion–so much so that St. Stephen’s offered to merge the congregations. That union never occurred, but with a failing membership, in 1810, The English Lutheran Church Zion became “a parish of the Protestant Episcopal Church, taking the corporate title of ‘The Rector, Church wardens, and Vestrymen of Zion Church in the City of New York.’” [2]

Now officially consecrated within the Protestant Episcopal church, on March 22, 1810, Zion Church marked the tenth Episcopal church in Manhattan. Sadly, tragedy was not far away when a late-night fire at a Mott Street fodder shop destroyed 35 buildings, among them Zion church, leaving only the exterior walls. The congregation “consisting mostly of mechanics not in opulent circumstances,” [3] was unable to rebuild, so the property was sold in 1817. Fortuitously, the purchaser, Mr. Peter Lorillard, held it with the parish intentions in mind–which were realized in 1818 after a Trinity Church-backed loan, allowing a return to on-site worship by late 1818. The edifice provided a home for their ministry but also made loan repayments difficult, leading to the property being mortgaged twice. While not ideal, these measures kept the church solvent.

In 1837, the church was led by the Reverend William Richmond, who arrived from St. Michael’s Church. While he would leave NYC in 1845, he also returned to St. Michael’s after finding difficulty in less cosmopolitan surroundings. This would form an important connection between the two churches in the years ahead.

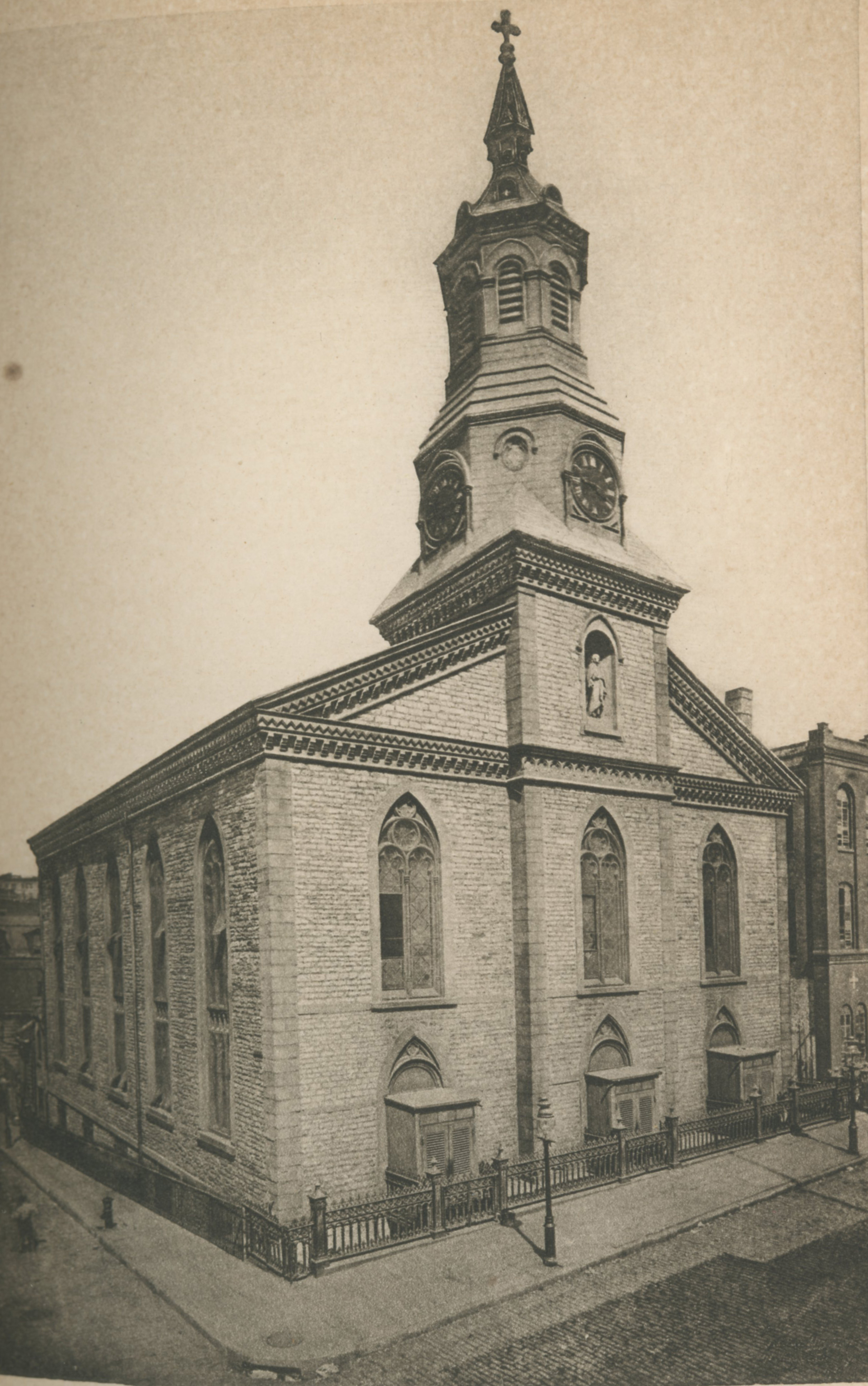

By the mid-century, the population had shifted, and the neighborhood surrounding the Mott Street church led the Reverend Richard Cox to seek a new home. Thanks to a gift of land, the parish was able to build a small brick chapel at 245 Madison Avenue on the southeast corner of 38th Street. Once services began on October 19, 1851, there was less need for the former home on Mott Street, which was purchased by the Catholic Church, and is still in use today as the Church of the Transfiguration. In heading north, critics chastised the church, claiming the Zion Church was ignoring poorer neighbors for literal richer fortunes. Nonetheless, the completed Wills & Dudley-designed, rough gray stone building fully opened for worship on June 11, 1854:

The Church consists of Chancel and Sacristy, (with a brick Chapel in the rear) Nave and aisles, with a Tower engaged in the west end of the North aisle, surmounted by a Spire. The outline of the Tower and Spire, which together are 165 feet high, is remarkably good as seen at a distance…The Walls are finished inside, throughout the whole church with plaster blocked off in imitation of stone; and it is the ugliest specimen of such imitation we have ever seen in a church.

a late-night fire at a Mott Street fodder shop destroyed 35 buildings, among them Zion church, leaving only the exterior walls.

The move did prove prosperous for the parish and the neighborhood. Perhaps too prosperous for the neighborhood, as the years following saw the construction of other large attractive churches vying for parishioners. By 1880, upon the resignation of another rector, Zion Church faced an existential question, “with a comparatively small building and weighty pecuniary burdens, should [it] continue the unequal strife with churches surrounding her by calling another rector, or should [it] consolidate with another parish in the vicinity.” [4]

The painful decision was made quickly, and in March of 1880, Zion Church formally merged with The Church of the Atonement (itself a strained parish in the wake of its rector forming The Reformed Episcopal Church in tandem with resigning from Atonement and siphoning many members). The union of Zion and Atonement alleviated several debts, lifted spirits, supported charitable works, and funded physical improvements, such as the redecoration of the Zion interior, an organ reconstruction, the addition of a chancel window as well as structural repairs, not to mention, an entirely new endeavor–the Zion Chapel on West 41st Street.

Sadly, within five years, history challenged these fortunes and the membership was in decline. The sale of the church property was proposed in 1890 with the hope that it would liquidate funds for a new facility in a less wealthy (and less religiously competitive) area. Within a month, a fire consumed St. Timothy’s West 57th Street Church that stood between Eight and Ninth Avenues. With the bishop’s approval and a plan for a new church and parish house on the combined seven lots, Zion and St. Timothy were merged on April 25, 1890, with the Zion Church holding its final services two days later.

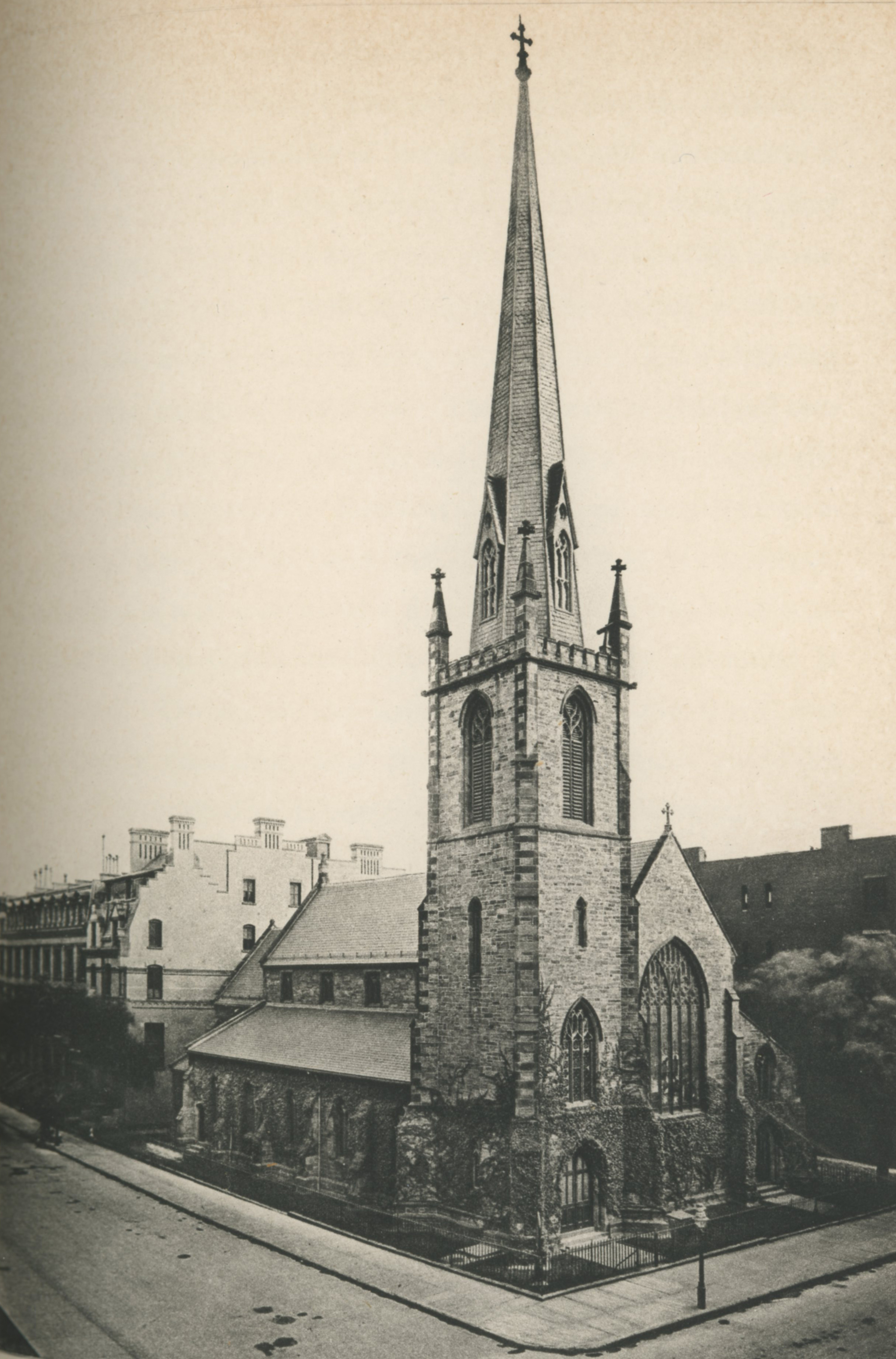

The unified congregation maintained the 41st Street chapel, now named The Chapel of Zion and St. Timothy and worshipped in a Methodist church as their new home was being built. To cut costs, “useless ornamentation was…eschewed by the committee and massive dignity substituted.” [5] Opened in time for Easter services on April 17, 1892, architect William Halsey Wood’s The Church of Zion and St. Timothy had a congregation of nearly 1500. The church

…has a frontage of 70 feet and is 165 feet deep. The style of the work is taken from the period of early Gothic architecture, is treated in simple, massive manner, bringing the whole design within the rightful use of brick and stone, and its constructive material. The principal feature of the exterior on the eastern side is a massive tower, with vigorously marked pier buttresses on the corners, with octagonal coneshaped pinnacles…Over the main entrances is a lancet window, surrounded by a rose window of harmonious proportions. Allesy on each side lead to the parish house, on 56th Street.[6]

While the facility held up, as the neighborhood saw an erosion of residential use as commercial demands expanded, maintaining the 1200-seat church proved taxing on the endowment. After thirty years, and with only half the seats full, as leadership weighed the next moves for the congregation, faulty wiring in the organ loft set off a blaze that expedited several decisions.

This time, the West Side YMCA served as a temporary home. Rebuilding in a commercial district made little sense, given the looming threat of a bridge at West 57th Street. Seeking a merger, Zion and St. Timothy courted various churches when they came upon St. Matthew’s Church.

St. Matthew’s Church

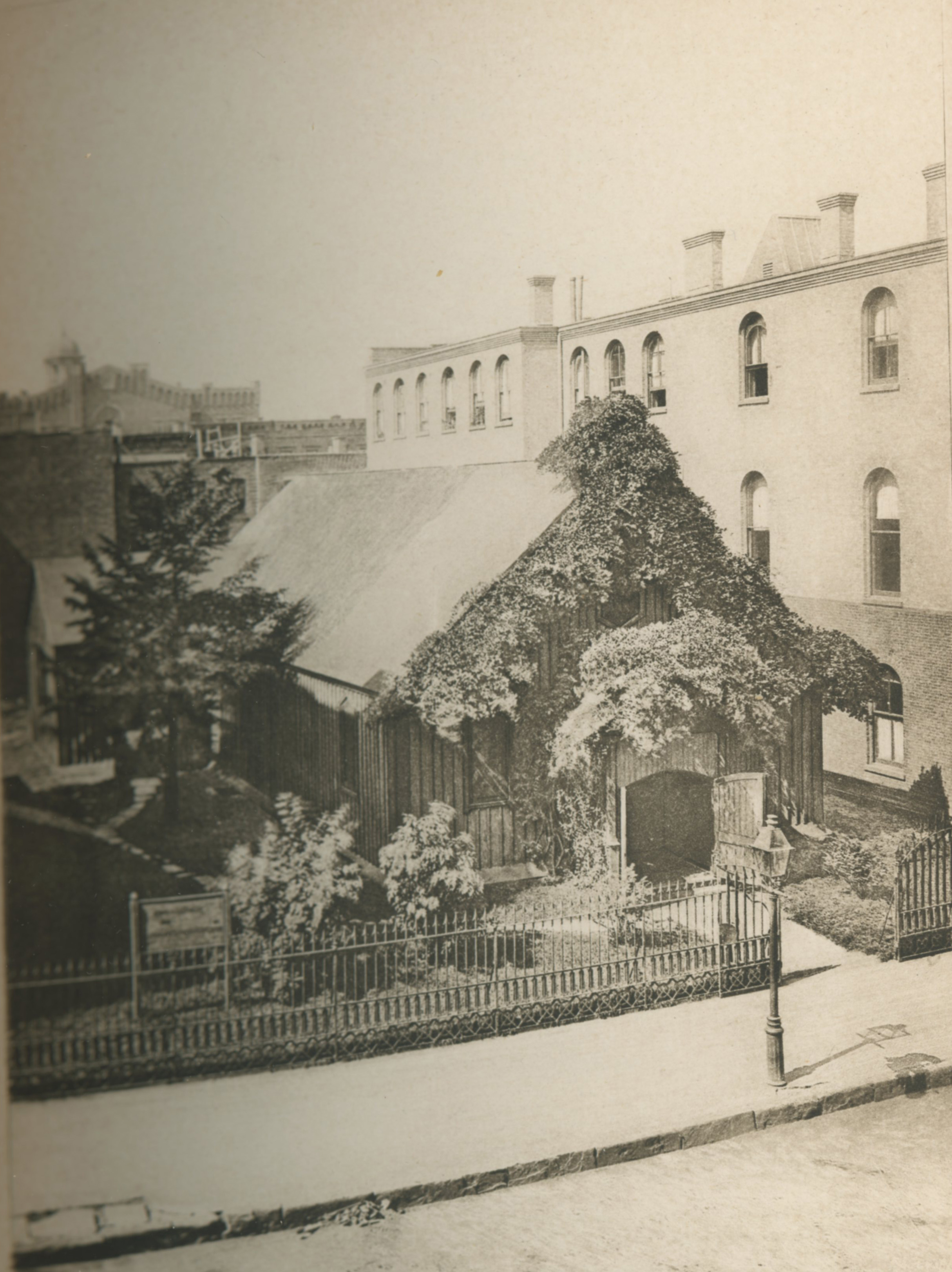

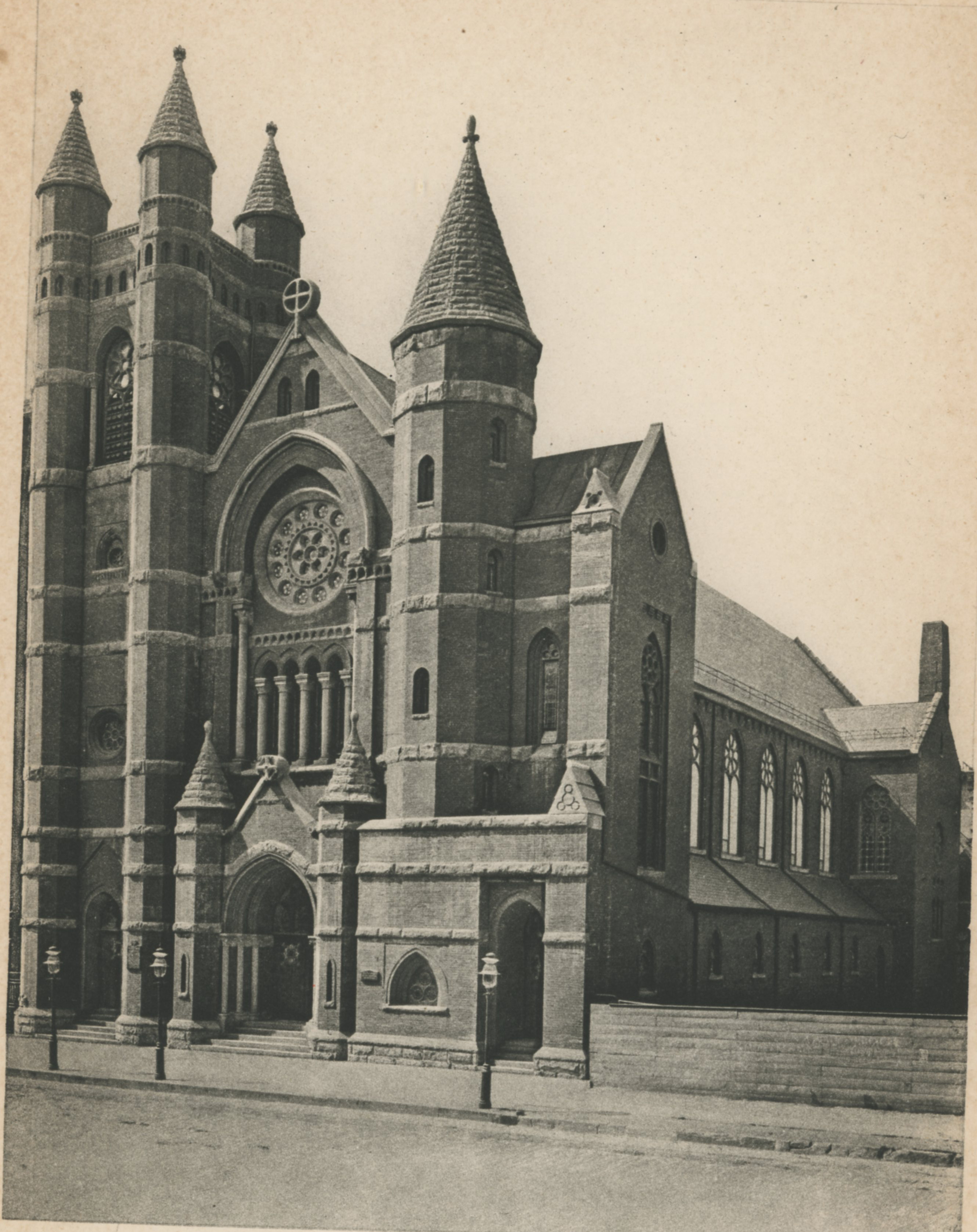

St. Matthew’s shares similarities with the Zion Church it would replace. Begun in 1867 along Central Park just south of 86th Street, it was an outpost of St. Michael’s Church on 99th Street and Amsterdam Avenue, intended to minister to German immigrants, and by 1869, they purchased two lots along Columbus Avenue (then, still 9th Avenue) between 82nd and 83rd street for a “cheap” wooden building. By June 1870, they laid a cornerstone for their “Bethlehem Chapel.” This presence allowed growth, and the influx of money led to the creation of St. Matthew’s Church in April of 1887. They took over the Bethlehem Chapel and kept it until 1892, when they purchased land at 26 West 84th Street to construct a Victorian Gothic Style Church, and sold the Chapel. Coincidentally, not only did William Halsey Wood design a Victorian Gothic sanctuary in 1891/1892 for the merged congregation of Zion and St. Timothy who merged in 1890, but he also designed the Victorian Gothic sanctuary on West 84th Street that would house the combined St. Matthew and St. Timothy.

Not long after relocating, they took on some notable missionary work.

Their ministry included uniting with St. Ann’s Church for the Deaf. A church with its own illustrious history, St. Matthews entered into a consolidation agreement in 1897 that included a specific chapel for them, which was realized in 1898 at 511 West 148th Street, very close to the New York School for the Deaf (then, known as the New York Institution for the Instruction of Deaf and Dumb). It prospered until the aforementioned school relocated to Greensburg, in Westchester County, in 1938. In December 1948, the mission work was transferred to the Diocesan Missionary and Church Extension Society of the Diocese of New York.

In addition to ministry, the Church of St. Matthew was making ties within the community and within the Episcopal Church.

On paper, the merger seemed biased towards St. Matthew’s. While St. Matthew’s endowment yielded $5,000 per year (approximately $91,000 in today’s dollars) and supported the St. Ann’s Chapel for the Deaf, the Zion and St. Timothy endowment yielded five times that sufficient funds to sustain the parish. The merger was completed in 1922. Rebranded as The Church of St. Matthew and St. Timothy, Zion was scrubbed from the name and the new century-old congregation came to be.

The new congregation tended to many expected duties, like a men’s group, a Ladies’ Circle, and a basketball team. The Depression and the Great War took their toll, however. A housing crisis loomed as the middle-class fled to the suburbs, weakening neighborhood bonds, and grand apartments and brownstones were carved up to smaller units. This reality only compounded in the wake of World War II “The entire Upper West Side, including West 84th Street, became an extreme example of massive deterioration and decay.” [7]

Since housing was an issue for the community, it became an issue for St. Matthew’s and St. Timothy’s. And in the mid-Century, the community was increasingly newcomers from Puerto Rico, who too often were faced with substandard housing. These were addressed head-on by the Reverend James A. Gusweller, who led the ministry from 1956 until 1973.

As part of the work of the church, he placed a particular focus on the needs of his youngest parishioners. At times outspoken, he addressed the hard realities of his community with a sharp dose of reality:

‘The inner city is the new frontier of the church…All churches are losing ground in the cities’

‘This is due to the failure of the church to adjust to the people around it. It has lost touch in the business and political worlds, and wields little influence in the outside world’

‘Each morning, I would go out and clear the beer cans out of the stairwells and off the sidewalk to keep the police from giving us a ticket.’

‘Our church is now a neighborhood institution, a community center. We have some activity for every age group, and we have a youth worker from the City of New York. We try to meet the needs of the broken society around us.’ [8]

These brief statements outline the motivations that brought the church to hire the firm of Blake/Netski to create an adjunct to the church, “The Center” to ease and enrich the lives of those in his community. Replacing two rowhouses due west of the church, The Center offered a venue for childcare, recreation and after-school activities.

And learning from the past of his congregation’s own struggles from Dutch to German and German to English, Gusweller had the foresight to begin Sunday School classes in Spanish for the youngest in his congregation.

It wasn’t even open for two years when a five-alarm fire destroyed the adjacent 69-year-old Victorian Gothic church designed by William Halsey Wood.

The inferno spread through a second-floor air shaft to the adjacent nine-story 1923 Neo-Georgian apartment building designed by George F. Pelham, causing damage to all floors. But while those residents returned and their building was restored, the church edifice was a total loss; firefighting efforts were hampered by fears the church steeple and nine-story bell tower would collapse.

Remarkably, the cool-headed response of community center director Sister Louise Brown, who treated the entire incident as a fire drill, meant that anywhere from 80[9] -120[10] children (depending on reports) from the eight pre-nursery classes held in the adjoining community center all safely evacuated the campus. Aside from one civilian injury–smoke inhalation–treatments were limited to two firemen of Ladder Co. 25, Henry Arnold and James Barrett–the latter treated at a field hospital on West 84th and Central Park West–and two patrolmen, Richard Maroney and Thomas Meehan of the West 68th Street Station who responded, each making three trips into the adjoining residential building before collapsing on the seventh floor during a rescue effort.

“Church building in which over 50% of the space is designed to serve the needs of the underprivileged and the community”

Suspiciously, according to the Daily News, this was the “second major blaze in a church building in that vicinity,” given that the West Side Institutional Synagogue at 120 West 76th Street was destroyed the Friday prior by a three-alarm fire.

The cause of the fire remains undetermined. Could it have been faulty wiring? Idle Youth? Retaliation against the Reverend Gusweller, who exposed the ‘jungle’ conditions neighboring his parish, and brought down the acting chief inspector, Frank P. Bacardi of the Manhattan office of the Buildings Department for accepting slumlord bribes? [11] Any are possible, but reports of the day seemed little concerned with discerning the true culprit. Given that The Cincinnati Post described Gusweller as “the crusading rector who is credited with lighting a new fire under the slum kettle” they may have foreshadowed what was to come or simply had a poor choice of analogy.

Given his long fight agist bribery, graft, and all forms of corruption which have “become too accepted in New York City,” having called out “bribes paid by slumlords to inspectors of the Department of Housing and Buildings, the police department, and the fire department” one might question how motivated these entities were in responding during the church’s time of need. [12]

As the congregation planned their future, the nearby Temple Rodeph Shalom at 7 West 83rd Street offered the parish use of their auditorium, which they accepted until they could hold services in the gymnasium of their restored community center while the ongoing construction work was completed.

The Current Church

The Church selected the Minnesota-raised architect Victor Frederick Christ-Janer for their new edifice. Having done experimental work in concrete and patented methods of preventing natural disasters, he seemed perfect for a congregation with a history of fires. Additionally, the firm of Blake/Neski, which designed The Center, had dissolved as Peter Blake took on new pursuits, and Julian Netski joined his wife Barbara in a practice best recognized for beach homes on Long Island.

Christ-Janer designed a building with a stark street frontage. Eschewing a 9-story tower, this rendition was more horizontal. Facing the street was a wall of board-formed concrete. Entry to the sanctuary was tucked in a glazed opening around the corner while the otherwise symmetric, concrete framed the cast-panel facade of the Community House. Prudent with finances, Christ-Janer continued the appearance of the panels with stucco melding with his building for a unified appearance. In reality, even in the church, the community was put first, with the common room closest to the street, buffering a non-axial church, only approached via a circuitous ramp.

The parish introduced its new “Church building in which over 50% of the space is designed to serve the needs of the underprivileged and the community” on Wednesday, October 8, 1969. The campus was designated a landmark within the Upper West Side/Central Park West Historic District on Tuesday, April 24, 1990, as the neighborhood continued to evolve. Under Reverend Jay Holland Gordon and Reverend Carla Rowland Guzmán, congregants from the Dominican Republic, Ecuador and Colombia, Cuba, Mexico, and other Latin American countries continue to fill the seats for what are now regular bilingual services. Along the way, difficult choices were made. The Reverend Frank Russ, (who preceded Reverend Rowland Guzmán) encountered economic difficulties. In order to preserve the programs of the St. Matthew and St. Timothy Neighborhood Center, they were ceded to Goddard Riverside. In their absence, new programs like The Phoenix Concerts launched and grew into their own independent nonprofit. St. Matthew and St. Timothy continue to serve the community with needed programming such as AA meetings and the Angels Basketball Program.

Continued focus on meeting community needs led to the creation of the St. Matthew and St. Timothy’s Housing Corporation, which has restored and maintained several more affordable housing units in the district. Today, it supports a 72-unit complex nearby, on West 83rd Street.

On Wednesday, October 9, 2024, LANDMARK WEST! holds their inaugural MUMFORD Award in this landmark, 55 years and one day after the opening.

References

[1] Clarkson, David. History of The Church of Zion and St. Timothy of New York: 1797-1894. G. P. Putnam’s Sons. New York. June, 1894. Pages 5-6.

[2] Wiggins, Henry and Daniel Arnheim. The Church of St. Mattew and St. Timothy 1810-1985. The Church of St. Matthew and St. Timothy. New York. 1985. Page 8.

[3] Clarkson, David. History of The Church of Zion and St. Timothy of New York: 1797-1894. G. P. Putnam’s Sons. New York. June, 1894. Page 23.

[4] Wiggins, Henry and Daniel Arnheim. The Church of St. Matthew and St. Timothy 1810-1985. The Church of St. Matthew and St. Timothy. New York. 1985. Page 14.

[5] Clarkson, David. History of The Church of Zion and St. Timothy of New York: 1797-1894. G. P. Putnam’s Sons. New York. June, 1894. Page 282.

[6] ibid. 315.

[7] Wiggins, Henry and Daniel Arnheim. The Church of St. Matthew and St. Timothy 1810-1985. The Church of St. Matthew and St. Timothy. New York. 1985. Page 26.

[8] Jeannin, Judy. “Church is Losing Influence, Must Adjust, Minister Says.” The Record. Hackensack, NJ. Tuesday, 25 September, 1962. P. 18.

[9] “Church, 9-Floor Apt. House Destroyed by Fire; 6 Hurt.” Daily News. New York, New York. Thursday, December 2, 1965. Page 3.

[10] “120 Students Unhurt in Church Blaze.” Press and Sun-Bulletin. Binghamton, New York. Thursday, December 2, 1965. Page 8.

[11] “Slum Crusade Bearing Fruit, Minister Says.” The Cincinnati Post. Cincinnati, Ohio. Wednesday, January 14, 1959. Page 7.

[12] https://www.wnyc.org/story/rev-james-a-gusweller/ via NYC Municipal Archives WNYC Collection, accessed 8/23/2024

Learn more about the MUMFORD Award at https://www.landmarkwest.org/mumford/

Building Database

Be a part of history!

Stay local to support the nonprofit currently at 26 West 84th Street: