View of 124-130 West 60th Street from northwest; Courtesy of The Paulist Fathers

St. Paul’s School

124-130 West 60th Street

by Jessica Larson

St. Paul the Apostle Church first established a school at 124-130 West 60th Street in 1886, ten years after construction on the church’s main building began. In 1891, a new school building was constructed, which initially served as an elementary school but later expanded its offerings.

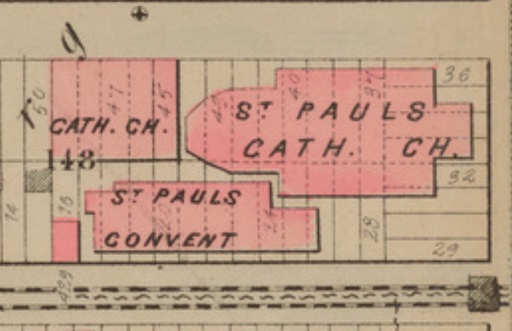

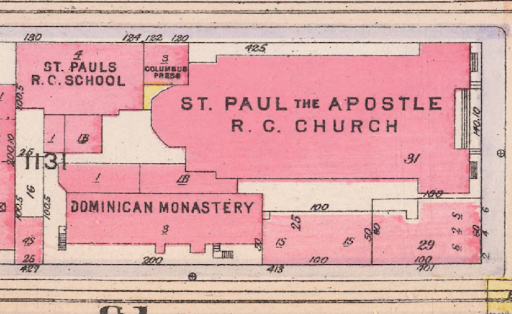

The Paulist Fathers, a Catholic apostolic society, took possession of roughly half of the lots on the east end of West 59th and 60th Streets, between Amsterdam and Columbus Avenues, in 1858. Based on fire insurance maps, a building initially existed on the lots that would become the school; an 1879 map marks it simply as “Catholic Church.” Its original use is unclear, but it’s possible that it was used for worship space while the church was under construction, as well as briefly for the school before the new building’s opening. The place of Catholic education in New York was a deeply contested issue in the nineteenth century. Public schools had enforced non-sectarian but Protestant teachings and practices, such as the use of the King James Bible (significantly different from standards today, “Protestant” was generally considered secular in this setting). Catholics argued that this unfairly disadvantaged Catholics, who paid taxes to support public school education but also had to pay to send their children to private Catholic schools to avoid Protestant indoctrination. Catholics argued that their private schools should, then, also benefit from tax dollars. After court battles throughout the 1840s, Catholics lost this fight and instead set about establishing an extensive system of Catholic schools (or “parochial schools”) throughout the city.

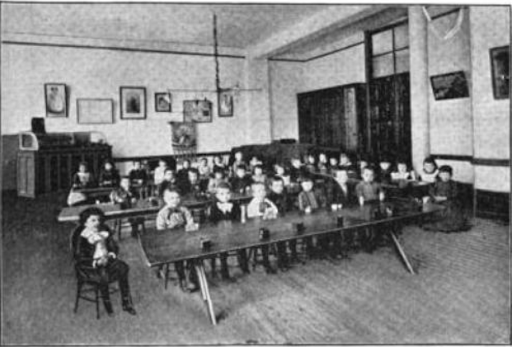

In 1891, the Paulist Fathers hired architect H. Palmer to design the new five-story brick structure for the school. According to visitors to the school, the student body was composed of both poor and well-to-do children, as well as Black children; there was no apparent discrimination between them (admittedly, these sources were also Catholic and surely biased). By the turn of the century, the school had roughly 1,250 students in attendance. Both boys and girls were admitted and included in classes together. Like many initiatives in schools, particularly for immigrant children, patriotism was deeply emphasized. This was a particular battle for Catholics, who had often been accused of being inherently incapable of ever truly entering the American citizenry due to their dual allegiance to the Vatican. The St. Paul School emphasized to students their duty in becoming American citizens.

Public schools had enforced non-sectarian but Protestant teachings and practices, such as the use of the King James Bible

While little documentation survives regarding the school’s design, it was purportedly well-ventilated and offered ample natural light. The school had a large playground space behind the building as well as a large basement room for recreation during bad weather. The building also had a separate large room devoted specifically to Sunday School, adorned with 8 ft x 9 in. paintings of scenes from the Bible, as well as paintings of missionaries converting Native Americans.

Within the building at 124-130 West 60th Street was a portion called “Columbus Hall.”

Columbus Hall was usually used for more social functions, often with the goal of fundraising. For example, in 1920 an amateur boxing match was held in the space; in 1898, the church hosted a benefit for blind workers that consisted of theatrical and musical productions; in 1895, 1,200 Catholic delegates met in the hall for the Catholic Total Abstinence Union of America’s twenty-ninth annual meeting; in 1916, the space was used to screen “wholesome” motion pictures every evening except Sundays.

During the construction of Lincoln Center during the 1950s and 60s, the church chose to sell off roughly 70% of its property on West 59th and 60th Streets. This included the school building, whose property was developed into middle-income apartments. The church’s building, however, remains and is open to worshippers today.

Resources:

“Benefit for the Bind Work Exchange.” The Sun. Sep 27, 1898: p. 4.

“Big C.T.A.U. Meet.” The Herald Statesman. Aug. 7, 1895: p. 1.

Catholic Total Abstinence Union of America. Silver Jubilee Gathering. New York: The Columbus Press, 1895.

Charity Organization Society. Directory of Social and Health Agencies of New York City, 20th Edition. New York: Charity Organization Society, 911

Charity Organization Society. New York Charities Directory, 10th Edition New York: Charity Organization Society, 1900.

“Church of St. Paul the Apostle.” Paulist Fathers. https://paulist.org/location/church-of-st-paul-the-apostle/.

Columbia University Center for Teaching and Learning. “Literacy Narrative: What’s Your Story?” WritLarge. https://writlarge.ctl.columbia.edu/view/84/.

Dunlap, David W. From Abyssinian to Zion: A Guide to Manhattan’s Houses of Worship. New York: Columbia University Press, 2004.

Mackim, Jim. Notable New Yorkers of Manhattan’s Upper West Side: Bloomingdale–Morningside Heights. New York: Fordham University Press, 2020.

“New in Brief.” The Brooklyn Union. Jan. 26, 1885: p. 2.

“New World Items.” The Catholic Bulletin. Jan. 08, 1916: p. 2.

“The Oppenheimer Cure” (ad). The Cosmopolitan 23, no. 6 (Oct. 1897): n.p.

“Paulist Entries Close.” The Brooklyn Citizen. Oct 14, 1920: p. 5.

“A Paulist Fathers’ Parish School.” The School Journal 70, no. 25 (June 24, 1905): p. 760-764.

Regan, Brian. Gothic Pride: The Story of Building a Great Cathedral in Newark. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2012.

Jessica Larson is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Art History, The Graduate Center, CUNY. She is also the Joe and Wanda Corn Predoctoral Fellow at the Smithsonian American Art Museum & National Museum of American History.