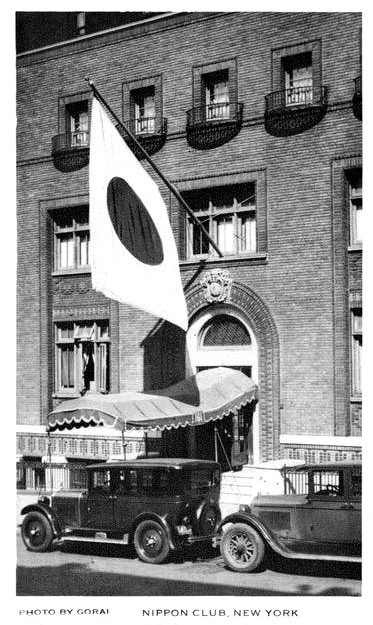

The Nippon Club (now Iglesia Adventista)

161 West 93rd Street

by Tom Miller

On May 14, 1905, The New York Times reported, “Leading Japanese residents of New York yesterday organized the Nippon Club, which will occupy a handsome house at 44 West Eighty-fifth Street, now a private residence.” The newspaper noted that the Nippon Club would be the only large organization of its kind outside Japan. “The membership will include Japanese bankers and merchants, those represented in the professions and the Government service.” The club was founded by Japanese chemist Jōkichi Takamine. (His development of the enzyme taka diastase, which breaks down starch, had garnered him a fortune of $30 million, according to the Japan Times decades later.)

After having leased the West 85th Street house for six years, on November 18, 1911, the Record & Guide reported that the Nippon Club had purchased the houses at 161 through 165 West 93rd Street, noting, “A 3-story clubhouse will be erected from designs by John V. Van Pelt.” Instead of demolishing the structures, however, on March 1, 1912, The Sun reported that Van Pelt had “filed plans for extensive alterations to the three three story dwellings,” adding, “The entire interior will be remodelled [sic] and the facade rebuilt.”

The interior, after the removal of all party walls, will have a large public dining room on the main floor, with a Sukiyaki room on the third floor and several large reception rooms. All of these rooms are to be finished in cedar wood, being carved and designed in the Japanese style. The three buildings will be converted into one structure, with the main entrance in the middle.

The renovations cost the club $30,000, or about $972,000 in 2025 terms. Van Pelt blended the Chicago School and Arts & Crafts styles. Interestingly, his plans included faience (glazed ceramic tiles) “under and over each window.” Instead, the final geometric designs were all done in two-toned brick. Stealing Van Pelt’s architectural show was the projecting cornice, described by Edison Monthly in 1915 as “the only discoverable hint of Asia.” Indeed, according to The Sun, “The roof will be of the peaked style covered with corrugated terra cotta tile, thereby giving the building its pagoda appearance.”

The Nippon Club moved into its new home in September 1912. The Japan Society Bulletin said it, “boasts all American fittings from billiard room to office, in addition to several floors furnished in Japanese style, where the tired business men feel again the spell of home in far Nippon.” As the bulletin suggested, the motif was expectedly Japanese with fusuma, or sliding screen doors, and Japanese-style furnishings including teakwood tables, bronze statues, and hand-made Japanese lanterns. There were a ballroom, billiards room, library, dining room, smoking room, and parlors.

He rushed into our parlor, where was thirty-one full dressed guests, and spoiled all their happiness

Items brought from the former clubhouse, according to The Sun, were “paintings on silk and velvet, fine specimens of the pillar print or kakemono-ye, a lot of tableware, including sets of beautiful, fragile Imari and lacquered tables and dishes.” The article noted, “The thing that the club places most value upon, for patriotic reasons, is a scroll from the Mikado presented to the club by Admiral Count Togo, last and most distinguished of Japanese visitors.”

The club was fashioned after exclusive New York gentlemen’s clubs, and The Sun remarked on January 21, 1912, “The first thing that will strike the curious inquirer is the astonishing resemblance the club bears to American clubs of the best type.” One notable difference, however, was the tradition that members honored upon arriving. “But the Japanese member is not so likely to insist upon its ranking as upon the great comfort if affords. To the Nippon he may go at evening after the day’s work is done and slip on his night gown and rest,” said The Sun. The article explained:

Not our kind of night gown, but a ukata [sic], which is a loosely, hanging kimono of light weight material that drops straight from the shoulders and is girt about the waist by a thin cord. The ukata [sic] is cool and comfortable.

The club routinely hosted dignitaries and countrymen. On the evening of February 24, 1915, the Nippon Club held a dinner for visiting officers of the Japanese Navy. Among the members present were the Consulate General of Japan, T. Nakamura; and several Japanese-born bankers. Not invited was a young man, Yataro Tanaka, who “wanted to pay his respects to the officers,” according to The Sun. In attempting to do so, he upset the traditional decorum within the club. According to the club’s manager, A. H. Ohnishi, at 10:30, “He rushed into our parlor, where was thirty-one full dressed guests, and spoiled all their happiness.”

Tanaka was ousted, but two hours later he returned. He broke into the front door, creating chaos amid the dignified event. In the West Side Court, A. H. Ohnishi complained that he, “broke our front door and got into our club house. He threatened our men by the violation at so late last night and there was no reason with him to do such things.” Tanaka was fined $5 for disorderly conduct.

Consul General Nakamura and other members hosted a dinner on November 30 that year in honor of Baron Ei-ichi Shibusawa. He was described by The Sun as the “foremost business man of Japan” and “to whom more than to any other his nation owes her commercial and industrial transformation, hater of jingoes, friend of peace and of America.” Shibusawa spoke on the ongoing war in Europe, congratulating America “on being the only world power that is not in the great war.” Ironically, given the events that would unfold nearly three decades later, he predicted that Japan and America “will be able to do much in preventing the recurrence of such disastrous calamities to humanity in the future.”

The Nippon Club continued to host eminent visitors. In September 1917, Viscount Ishii “and the other members of the Imperial Japanese Commission” were guests here; on the evening of July 23, 1918, a dinner was held in honor of Prince Yoshihisa Tokugawa; and on November 17 that year, the club hosted a dinner for visiting retired Japanese Army Colonel H. H. Hirayama.

On July 23, 1922, The New York Times reported that Jōkichi Takamine had died, saying he “founded the Nippon Club” and was “widely known for his work for friendly relations between Japan and United States.” Takamine’s body was brought to the Nippon Club for a memorial service on July 24. The New York Times reported that his casket, upon which were crossed Japanese and United States flags, was “surrounded by more than three hundred floral pieces from prominent Japanese and American friends.” The following morning, Takamine’s body was taken to St. Patrick’s Cathedral for his funeral.

Prince and Princess Tokugawa visited New York in 1931. On April 13, The New York Times reported, “The Nippon Club at 161 West Ninety-third Street, composed of leading members of the Japanese colony here, was eager to have the royal couple visit their clubhouse, and the Prince and Princess found time to do it.”

Three years later, the Prince was back. On February 27, 1934, The New York Times announced, “Prince Iyesato Tokugawa last night extended greetings to his countrymen in New York at a dinner held in the Nippon Club…The speeches were in Japanese.”

On February 11, 1940, a celebration of the 2,600th anniversary of the founding of the Japanese Empire was held here. The New York Times said that 250 members made “solemn pledges of fealty to Emperor Hirohito.” Consul General Kaname Wakasugi conducted the event. “Later they rejoiced over buffet tables laden with native delicacies, sang folk songs and toasted the world’s oldest dynasty in sake, a rice wine.”

Later that year, the clubhouse became involved in at least one Nazi espionage incident. Born in Germany, William Sebold became a naturalized U.S. citizen in 1936 and worked in aircraft and industrial plants. Three years later, he was approached by the Gestapo who persuaded him to cooperate with the Reich. In the meantime, Everett Minster Roeder was a draftsman who designed materials for the U.S. Army and Navy. Sebold delivered German instructions to Roeder in various places throughout the city. According to Norman Ridley in his Spying for Hitler: Nazis Who Infiltrated America, “At the end of October 1940, Sebold received instructions from Germany to send Roeder to a rendezvous at the Nippon Club at 161 West 93rd Street. This would reveal yet another method that the Abwehr were employing to have stolen documents transported safely back to Germany.”

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese launched a surprise attack on the United States fleet at Pearl Harbor. American reaction was swift. The next day, The New York Times published a photograph of the steward of the Nippon Club locking the doors under the watchful glare of a policeman.

The newspaper reported, “The Nippon Club at 161 West Ninety-third Street was closed by the police. Twelve Japanese who were there when the police came were escorted to their homes. Silent crowds watched their departure. There were no demonstrations.”

The New York Times published a photograph of the steward of the Nippon Club locking the doors under the watchful glare of a policeman

The clubhouse was seized by the Office of the Alien Property Custodian and it sat dark for more than two years. On February 6, 1944, The New York Times reported that the Alien Property Custodian had sold the building to the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks. The article noted that the lodge “would be occupied some time in April after alterations.”

Two weeks later, on February 21, an auction of the contents of the Nippon Club was held. Rampant anti-Japanese sentiments, however, greatly affected the bidding of the rare and valuable items, including eight ceremonial Japanese swords and the custom-made furniture. A spokesman said, “nobody seemed to be very interested.”

The prediction that the Elks would move into the clubhouse in April was optimistic. It was not until December 16, 1944 that “the mother lodge of Elkdom” dedicated the building, as reported by The New York Times. The structure and the renovations had cost the fraternal organization $75,000–about $1.3 million today.

Fourteen years later, the Elks sold the property to the American Theatre Wing. Renovations resulted in rehearsal halls in the basement, first and second floors; offices and half of a duplex apartment on the third; and the top floor of the duplex on the fourth.

On September 15, 1958, Mayor Robert F. Wagner officiated at the dedication of the new headquarters. According to its president, Helen Menkin, the new building would permit “our organization to carry out our expansion ideas more effectively.” It held full-time classes for 400 students with a faculty of 40 teachers. Among the well-known names of the theater who attended the event were Ed Begley, Lawrence Lagner, Miriam Hopkins, and Mrs. Bert Lytell.

The American Theatre Wing sold the property in 1968 to a Seventh-Day Adventist Church, Iglesia Adventista Broadway. The congregation converted the lower floors for worship purposes with residential spaces on the upper floors.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

Return to Spirit of the City

Building Database

Be a part of history!

Stay local to support the nonprofit currently at 161 West 93rd Street: