2067 Broadway

by Tom Miller

In 1920, at the age of 30, Italian-born Rosario Candela opened his architectural office. By the end of the decade, he would be famous for his soaring and luxurious apartment buildings. But in 1922 he was commissioned by Victor M. Earle to design a much more modest structure at 2067 Broadway, between 71st and 72nd Streets.

Completed in 1923, the no-nonsense office-and-store building featured a two-story storefront framed in white terra cotta. Candela used the material to outline the vast central widows of the brick-faced upper floors, topping the framework with a molded lintel.

Segall’s Pharmacy moved into the retail space, while the upper floors filled with tenants, many of them connected with the real estate industry. In 1923 Rosario Candela was drawing plans for several Upper West Side apartment buildings for syndicates working from this address—most likely headed by Victor M. Earle.

Tenants in 1930 included the Colchester Realty Corporation, a real estate development firm; and the Eureka Mercantile Service, a debt collection agency. A decade later, occupants were becoming somewhat sketchy. While legitimate tenants like the West Side Garage Owners Association offices and the Fleetlyn Corporation, real estate operators, operated from the building, and an Atlantic & Pacific grocery store occupied the retail space, others were less mainstream.

In 1923 Rosario Candela was drawing plans for several Upper West Side apartment buildings for syndicates working from this address—most likely headed by Victor M. Earle.

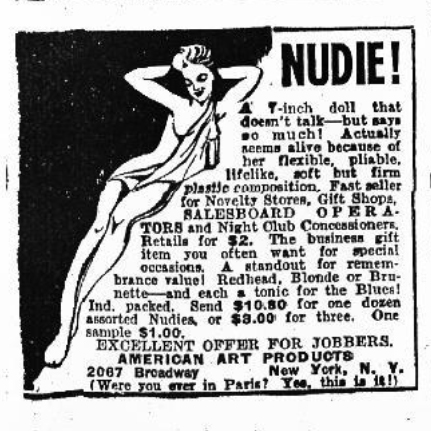

In 1943 the American Art Products advertised its “Nudie” in Billboard magazine. The ad described the product as a “7-inch doll that doesn’t talk—but says so much! Actually seems alive because of her flexible, pliable, lifelike, soft but firm plastic composition.” The Nudie was available in “Redhead, Blonde or Brunette—each a tonic for the Blues!”

Operating from 2067 Broadway in 1946 were the Mudial Gift Co., which sold wholesale gift items, like men’s Swiss watches for $4.57 each; and the Atomic Light Co. which offered novelties like expansion watch bands, an “automatic pancake turner,” and its trademark Automatic Lighters.

The second half of the 20th century saw another change in the tenants. In 1950 Proofs & Morse, Inc., a realty firm was here, and by the early 1970’s, the United States Construction and Remodeling Co. had its officers in the building. Around 1975 the Planning Assistance branch of the Planned Parenthood Federation of America, Inc. moved in.

Amy’s restaurant took over the ground floor around 1981, while the second floor became home to the Star Nail salon, run by two Korean cousins who had just emigrated from Seoul. In 1985 Yung-sook Choy worked from 10 a.m. to 8 p.m. except on Sundays. She told Susan Heller Anderson and David W. Dunlap of The New York Times, “Americans are very kind. They speak slowly and some now correct my English. A follow-up a year later by The New York Times journalist Anne-Marie Schiro drew the comment, “It is a pleasant salon above a restaurant and draws a loyal following of West Side Women.”

Those patrons were, most likely, unaware that on an upper floor was the AAA Supreme Escorts, which ran its questionable service from at least 1983 through 1984. A more respectable tenant was the publishing firm of Gumbs & Thomas, which moved in around 1986 and would remain at least through 1992. It was joined in the building around 1988 by Seesaw Music Co., publishers of classical and sacred music. The firm leased space for at least two decades.

The New York Times reported, “chicken smells wafting into his office led to Mr. Lichtman’s protest.”

Edmondo Schwartz opened a Kenny Rogers Restaurant in 1996, quickly causing problems with other tenants. Attorney Aaron Chess Lichtman occupied the former nail salon space directly over the restaurant. The New York Times reported, “chicken smells wafting into his office led to Mr. Lichtman’s protest.” That protest was in the form of a sign taped onto his window that read “Bad Food,” with an arrow pointing down. Schwartz sued Lichtman for $2 million, but the attorney won on the grounds of free speech.

In 1997 the restaurant closed, then reopened after renovations and expansion. Ismail Hamed, director of operations for Kenny Rogers, said the customers “had suggested the types of foods they wanted added to the menus.” But a change in the menu did not solve the problems. In July 1998 a sign appeared on the door saying, “Closed for Renovation.” A few days later it was replaced by one reading “Store for Rent.” The restaurant owner owed more than $300,000 in back rent.

For a while, the restaurant space was home to Soma Soup, which opened in September 1999. More recently the ground floor is vacant, possibly a victim of the pandemic. Through it all, Rosario Candela’s little-known, early work is essentially intact.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

Building Database

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the businesses at 2067 Broadway: