2121 Broadway

by Tom Miller

On December 20, 1890, the Record & Guide reported on the recent development of The Grand Boulevard, saying, “We have chosen to describe this important thoroughfare because it is one which has a great future before it. It is the finest artery, as well as the widest, running through the western side of the city, and is the most central avenue between Central Park and the North [i.e. Hudson] River. It is, in fact, the very backbone of this section.” The northwest corner of the Boulevard (renamed Broadway around 1898) and 74th Street, however, was not so uplifting. Next to the vacant corner lot were “two two-story brick houses, with fish and oyster store, etc. on first floor.”

That all was about to change. In 1894 developer Jere W. Dimick hired architect Martin V. B. Ferdon to design a modest replacement building on the site of the vacant lot and the two houses. His plans, filed in September, called for a three-story brick “store and dwelling” (i.e. apartment building) to cost $3,500 (about $115,000 in today’s money).

Theresa D. Browning, Dimick’s daughter, inherited the property. (She was the wife of real estate operator William H. Browning, who would become less famous for the remarkable building he erected than for his notorious attraction to underage girls.) In March 1899, Theresa purchased the 24-foot-wide vacant lot to the north. The soaring property values along the thoroughfare were reflected in the $29,000 price she paid. And in 1902 she purchased the vacant lot at 229 West 74th Street. She now had her father’s building enlarged to the west and north and a fourth floor added. Entrances at 2121 Broadway and 229 West 74th Street led to the upper floors, while stores lined the Broadway sidewalk. The upper floors were converted for commercial purposes.

The building filled with a wide variety of businesses. Among the early tenants on the upper floors were Thomas A. Loftus & Co., interior decorators; a branch office of the George W. Thedford Coal Co.; and the Coles Construction Co. offices. The Broadway shops were home to Jacob Bauerman’s “ladies’ tailor and designer of garments,” David W. Fittong’s electrical shop; and Barrett, Nephews & Co. “Old Staten Island Dyeing Establishment.”

Edward Goodman was set upon by motor bandits, who robbed him of $2,000 while a crowd looked on

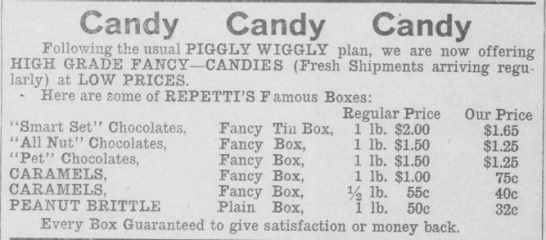

On October 3, 1908, Repetti, which deemed itself the “King of Caramel Makers,” opened its new store at 2125 Broadway. Its opening announcement read:

Saturday—come to the opening of our new Candy Shop, Soda Fountain and Parisian Ice Cream Garden, 2125 Broadway, between 74th and 75th Streets. Souvenirs. Music.

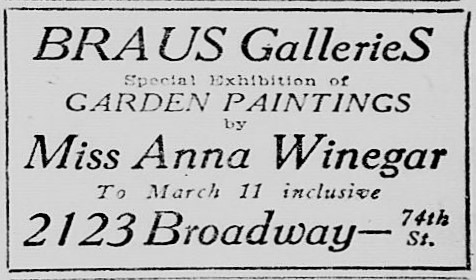

The Repetti candy and soda fountain was replaced in 1917 by a C & L Lunchroom, which would remain in the space at least through 1930. In the meantime, Braus Galleries had opened next door at 2123 around 1915. The high-end dealers also ran a gallery at 358 Fifth Avenue. An advertisement in the Winter Exhibition Catalog of the National Academy of Design in 1917 offered, “Paintings by American Artists, Mezzo tints in color by the foremost Engravers, Etchings and other choice Prints, Correct frames for all pictures.”

On April 15, 1918, two of the Braus Gallery executives, looked out the window to see a horrifying incident taking place. The New-York Tribune reported, “Walking down Broadway at Seventy-fourth Street at 2 o’clock yesterday afternoon, Edward Goodman was set upon by motor bandits, who robbed him of $2,000 while a crowd looked on.” Goodman was treasurer of the Eighty-First Street Theatre and was on the way to the bank in the Ansonia Apartment building to deposit the cash when he was assaulted.

But he proved not to be an easy mark. “Clinging desperately to the bag and calling for assistance, Mr. Goodman struggled with the robbers, and the trio, interlocked and raining blows upon each other, reeled west on Seventy-fourth Street.” After a 10-minute battle, a limousine pulled up, the men wrested the bag away, and jumped in. “They were not quick enough to avoid Goodman, however,” said the newspaper. “He leaped after them and was pulled bodily into the car.

A Mr. Gogin and H. A. Heald burst from the Braus Gallery and began to chase the limousine in another car. As the two cars sped through the Upper West Side, Gogin and Heald “shouted for help.” The article said, “They could see a violent struggle going on in the limousine.” Finally, at 78th Street and West End Avenue Goodman was tossed out. Gogin and Heald pursued the getaway car “through Seventy-ninth Street, Riverside Drive and Broadway,” but eventually lost it. Goodman was treated for numerous cuts and bruises. The money was never recovered.

Two months before the incident, Therese Browning had hired architect Henry Otis Chapman to make alterations to the building. His Arts & Crafts style brick panels below the fourth floor violently fought with the more ornate panels of the 1902 remodeling one floor below.

Around 1919 H. Milgrim & Brothers, ladies tailors took two floors. The firm was owned by Municipal Court Judge Aaron J. Levy, described deridingly by The New York Call on February 4, 1920, as “the big boss of the shop” and “a professional ‘East Sider’ and one of the ‘Grand Street Boys;’ a sterling patriot and fiery exponent of true Americanism—if you take it from Aaron J. Judge.” In 1920 the firm advertised for “boys” in the “high-class establishment,” promising “steady work, pleasant surroundings and attractive salary.” The teens worked, for the most part, as messengers, taking the high-priced finished garments to the homes of its clients.

In February 1920 250 employees of H. Milgrim & Brothers walked out on strike. The New York Call explained, “Judge Levy made the strike inevitable when he told the shop committee, which had been negotiating with him for the raise, ‘I know these people are entitled to a raise, but I won’t give it to them.’”

Levy’s scant salaries most likely prompted a bookkeeper and two messenger boys to embezzle from the firm beginning in 1920. Ralph Brosky, the bookkeeper, in all likelihood, came up with the scheme. When Samuel Schlimwitz and George Fein collected cash on C.O.D. deliveries, they brought it back to Brosky, who did not enter the receipts in the books. Later that evening they would meet and divide the proceeds. Almost unbelievably, the scam went on unnoticed for two years, until the amount the trio had embezzled had reached $61,000—closer to $985,000 today. They all confessed and were sent to prison.

By 1925 the top floor was home to the Amateur Billiard Club. In 1939 the Midtown Dental Supply took the entire second floor, and the third floor was home to the Manhattan Weavers, the Mellquist Reducing & Cosmetic Salon, and the office of John Meenan, Inc., real estate. An advertisement for the ladies-only Mellquist Salon in 1938 offered “Steam-Cabinet and Swedish Massage” for $1.

Almost unbelievably, the scam went on unnoticed for two years, until the amount the trio had embezzled had reached $61,000—closer to $985,000 today.

The building was renovated in 1950 to accommodate a restaurant on the ground floor, and “clubrooms” on the fourth. (The Unity Bridge Club had occupied the space in 1940 and may have still been here.) The new restaurant space became home to Traymore. On November 11, 1950, The Advocate acclaimed, “Here you can get excellent food in quiet surroundings—good service and at reasonable prices. No place in New York can you get a better luncheon.”

In 1955 the estate of William “Daddy” Browning sold the property. The upper floors were home to two music publishers in the succeeding years. Highgate Press was here for years beginning around 1958, and Galaxy Music Corp. rented space from about 1961 through 1974.

At the same time, the Fairway Button Company operated from one of the upper floors, run by Leo Glickberg and Wallace Weiss. The two dissolved the firm in 1962. Glickberg had founded Fairway Market in 1933 with Nathan Glickberg. Fairway Fruits and Vegetables occupied the corner store, and by 2003 it had taken part of the second floor for the Fairway Café.

A major renovation came in 2006-2007. Fairway Market now engulfed the entire ground floor. Suzy Gershman, in her 2007 Born to Shop New York, said “The grocery store Fairway…has redone itself and competes more than ever with Zabar’s.” And in his 2009 The Architectural Guidebook to New York City, Francis Morrone called Fairway Market, “a warehouse/cornucopia spilling its fruits, vegetables, and sundry other delicacies onto the sidewalk out front. It is the very picture of metropolitan abundance.”

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

Building Database

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the local businesses at 2121 Broadway:

Meet Angel Kaba!