The Apthorp

by Tom Miller

Following the death of his father in 1890 William “Willy” Waldorf Astor became America’s wealthiest man. Family problems (he was embroiled in a vicious feud with his aunt and next-door neighbor Caroline Schermerhorn Astor) and other circumstances prompted him to abandon New York for England the following year. When he gave up his American citizenship in 1899 to become a British subject, he became generally unpopular across the country.

Living abroad did not bring Astor’s vast real estate operations to a halt. They went on, run by the “Astor Estate” which sometimes used the architectural firm of Clinton & Russell. Such was the case, for instance, in 1900 when the firm designed upscale The Astor Apartments at Broadway and 75th Street. The partners, Charles W. Clinton and William Hamilton Russell, were hired again by the Astor Estate to erect the massive Apthorp Apartments in 1906. The project would engulf the entire block between Broadway and West End Avenue, from 78th Street to 79th Street–property which Astor had purchased in 1879.

Astor named the building as a nod to the 18th century estate of Charles Ward Apthorp on which land the site stood. The Apthorp mansion had been demolished by the city relatively recently, in 1891. The project cost Astor a reported $6 million–in the neighborhood of $170 million today.

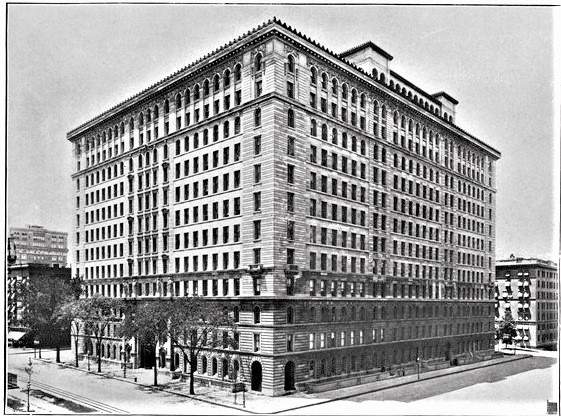

The structure, completed in 1908, was an architectural stunner. Clinton & Russell had designed a regal 12-story Italian Renaissance Revival building faced in limestone. As construction drew to a close, newspapers across the country described the building. On March 11, 1907 Duluth, Minnesota’s Evening Herald entitled its article “Hundred Homes Under One Roof / Apthorp Apartments in New York Cover Whole City Block.” It went on to say “One hundred commodious homes under one roof–this will be the unique feature of a massive structure almost completed by William Waldorf Astor, on the upper west side of this city.”

The article spoke in superlatives. “Its total floor area will be eleven and a half acres…In size and ground area the Apthorp apartments will not only rival the big skyscrapers in the financial district, but they will be of the same type of construction which makes these big structures the safest and most enduring to be found in any city in the world.”

Readers were told of the 1,500,000 square feet of fireproof tiles, the terra cotta partitions which “if placed in line would reach nine miles,” the “thousands of tons of steel, valued at $500,000 dollars” used in the framing,” and the 25-miles of steel columns and beams for the floors. “When finished, this mammoth apartment house will be the most striking structure on the upper west side,” the article portended, noting “The location is right in the heart of one of the finest residential districts of the city.”

The Broadway and West End Avenue elevations were nearly identical, each having a grand, three-story arch protected by immense iron gates. Pairs of tall engaged Corinthian columns flanked the arches and carved female figures in deep relief reclined in the spandrels. Above the third floor cornice four sculpted figures topped each column.

“Its total floor area will be eleven and a half acres…In size and ground area the Apthorp apartments will not only rival the big skyscrapers in the financial district, but they will be of the same type of construction which makes these big structures the safest and most enduring to be found in any city in the world.”

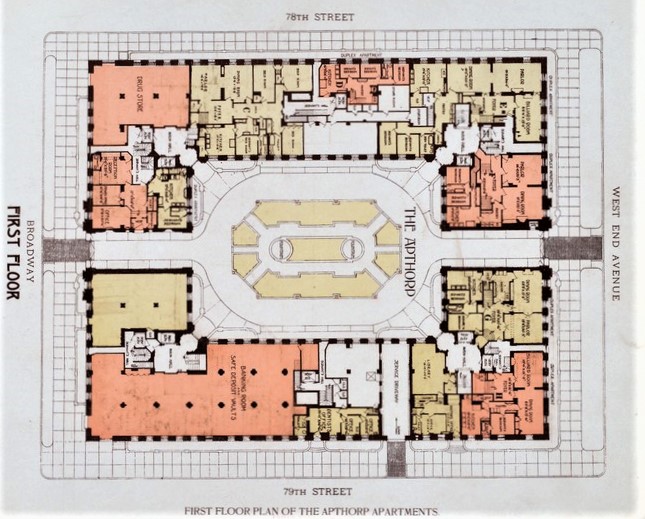

The issue of light and ventilation to interior rooms of the block-engulfing structure was solved by designing it around a large courtyard. The World’s New York Apartment House Album described it as “containing flowers, shrubbery and fountains.”

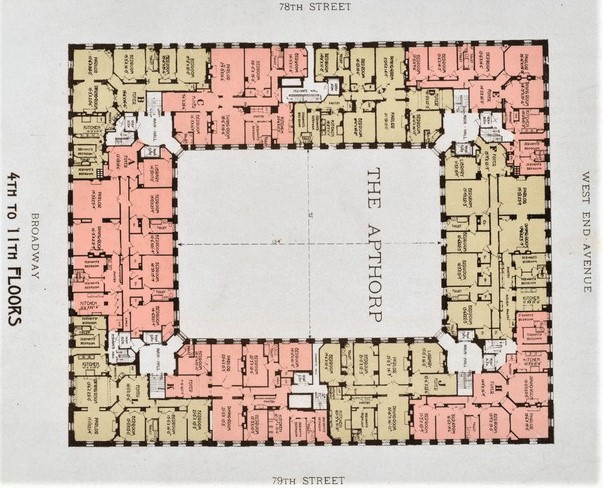

There were commercial spaces on the Broadway ground floor, as well as five two-story apartments, “the living rooms of which are on the ground floor and the bedrooms above,” according to The World’s New York Apartment House Album. On the third floor were twelve apartments, varying from six rooms with a bath to nine rooms and three baths. Each of the upper floors held ten apartments.

The Apthorp residents were, of course, well-heeled and highly visible professionally and socially. Among the initial tenants was broker Lloyd W. Seaman, a trustee of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Abel I. Smith a former New Jersey Assemblyman who lived here with and adult son, Abel I. Smith, Jr.; and civil engineer James Daniel Mortimer and his wife.

It was Mrs. Mortimer who regularly appeared in the newspapers, most often for her role as president of the Beethoven Society. The group, composed of wealthy members, provided “beneficent activities,” as described by The New York Times. As the as the name suggests, those events focused on the music of Ludwig von Beethoven. But she also appeared in society columns for her entertainments, as on March 7, 1913 when the New York Tribune remarked “A card party will be given on Monday afternoon at 2 o’clock, at the residence of Mrs. Mortimer.” The Mortimer apartment was large enough for a tea dance and reception for the Beethoven Society’s “choral” on March 12, 1917.

Readers of the New York Herald on January 10 that year may have concluded that resident Elbridge Gerry Snow, Jr. had more money than common sense. The newspaper reported that he had purchased a rowhouse on West 78th Street for his Pekingese show dogs and provided them with five servants.

To ensure that the pedigree canines were comfortable in their surroundings, Snow had the house decorated to “gladden the heart of a mandarin…Interior decorations on all three floors of the kennel mansion are Chinese. There is a hospital for the dogs. Also there is a playroom, a reception room, a bedroom, a puppy room, a show ring and many other things that go to make up a happy dogdom,” said the article. Interviewed in his Apthorp apartment, Snow explained “It is a new hobby with me, and I mean to have some real show dogs. Mrs. Snow is heartily in accord with me in the diversion…The kennel in West Seventy-eighth Street may seem a little bit elaborate, but it adds to the comfort of the dogs.”

Other well-known residents at the time were Jean Baptiste Martin, proprietor of the society restaurant the Cafe Martin; and engineer John Findley Wallace, who was the first chief engineer of the Panama Canal. The New-York Tribune called him “one of the best known civil engineers in the world.” He was as well the chairman of the Chicago Railway Terminal Company and engineering consultant to several large corporations.

The early 1920’s saw Theodore B. De Vinne, head of the large De Vinne Press, in the building with his wife, Lillian; as well as architect Harry P. Knowles, his wife the former Esther McDonald, and their daughter Esther. Knowles was perhaps best known for his 1908 Masonic Temple on West 23rd Street. The 52-year old was taken to the French Hospital on New Year’s Day 1923 with an attack of appendicitis. He died there following the operation.

After living in the Apthop for two decades, Lloyd W. Seaman died in his apartment on October 20, 1929. The New York Times reported that his estate topped $10 million (more in the neighborhood of $147 million today), $6.25 million of which went to charity.

Millionaire candy maker Alexander McDonald Powell and his wife lived in the Apthorp at the time. He had been a leading confectioner, with a handsome building on Hudson Street, for 57 years. After his death from a heart attack while on vacation in Canada, his funeral was held in his Apthorp apartment on July 13, 1931.

After having been in Astor hands for seven decades, the property was sold in July 1950 to the newly-formed Apthorp Estates, Inc. The new owners improved the property with a three-story underground garage opening onto 79th Street in 1956, then sold it the building the following year. In reporting the sale on August 26, 1957, The New York Times noted “The property contains 158 apartments and thirteen stores.”

The second half of the 20th century saw residents who continued to be in the spotlight–although a brighter and broader spotlight. On February 16, 1972, for instance, syndicated columnist Jack O’Brian wrote “Lena Horne’s return to work in Vegas has a simple practical purpose: to decorate the sumptuous new flat she just acquired in the Apthorp apartments.” Other celebrities in the building would include Rosie O’Donnell, Conan O’Brien, George Ballanchine and Al Pacino.

Entertainers living in the Apthorp in 2000 included Cyndi Lauper, actress Kate Nelligan, and filmmaker Nora Ephron and her writer husband Nick Pileggi. But not everything was tranquil within the fabled building at the time. In her article in The New York Times on May 12 that year entitled “Palace Revolt,” Katherine Marsh wrote “With its 3,000-square foot apartments and airy interior courtyard, the Apthorp embodies the dream of New York living. These days, for some, it also represents the nightmare.

“In the last few years, tenants have heard bizarre stories involving jewel thefts and a mysterious dead body.” The upheaval prompted Ephron (who filmed part of her 1986 movie Heartburn in the Apthorp) and Pileggi to leave in 2002 after nearly two decades in their eight-room apartment. She told Marsh, “We left because they doubled our rent and then doubled it again.”

Other New Yorkers may not have been sympathetic. Cyndi Lauper, said the article, was “suing to get her rent rolled back from $3,250 to $507.” And the owners asserted that rent increases ($25 per room per month) were necessary to maintain the nearly century-old structure. They had just spent $1.8 million to replace the eleven elevators.

As tenants moved out, their apartments were being upgraded and modernized. At the time of Marsh’s article, a four-bedroom, four-and-a-half bathroom apartment had just been revamped with a granite kitchen floor, new plumbing and wiring and a marble Jacuzzi in the master bath. It went on the market for $25,000 per month.

“In the last few years, tenants have heard bizarre stories involving jewel thefts and a mysterious dead body.” The upheaval prompted Ephron (who filmed part of her 1986 movie Heartburn in the Apthorp) and Pileggi to leave in 2002 after nearly two decades in their eight-room apartment. She told Marsh, “We left because they doubled our rent and then doubled it again.”

The Apthorp was purchased by Maurice Mann in November 2006 for about $425 million. He described it saying “This is the equivalent of buying a great Picasso.” Three years later he and his partners, Ralph Braha and Joe Nakash (founder of Jordache jeans) began a condo conversion; but it did not go well. On January 12, 2009 The New York Times reported that a lender, Apollo Real Estate Advisors, “could begin foreclosure on Thursday if the owners do not resolve their internal dispute.”

Shockingly, the article reported that lawyers were working on a deal that “would force one of the owners Maurice Mann, to surrender management.” Mann was not so sure. He told a reporter “I control the Apthorp 100 percent.”

Five months later journalist Josh Barbanel commented “The Apthorp, one of New York’s grandest apartment buildings, has been an ugly duckling of New York real estate development for many months, despite its sprawling interior courtyard and vaulted limestone arches.” The problem was not only the feuding among the owners, but that the real estate market had plummeted. Prices for the potential condo plan had fallen from as high as $3,000 per foot to $1,950. Nevertheless, potential buyers were looking, including Alec Baldwin (who was considering combining three 11th floor apartments into a 6,000-square foot space), Sarah Jessica Parker, Matthew Broderick and Tommy Mottola.

On August 1, 2006 Jennifer Gould Keil began her article in the New York Post saying “If a single Manhattan building could sum up the saga of New York City’s big, bad and wacky real estate business, the Apthorp would have it covered.”

With dozens of apartments vacant, real estate mogul Joe Sitt had entered into contract to buy 71 of the apartments for the enormously discounted price of $120 million. The New York Post article said “The deal appears to include development rights for the roof, which are worth at least an additional $25 million.”

The majestic Apthorp weathered the bad times. The following month composer Jonathan Sheffer moved into an apartment after interior designer Robert Couturier had transformed it. He equated Sheffer’s resulting master bedroom to the “best London hotel room ever.”

Oscar winning Jennifer Hudson had purchased her 3,000 square-foot 11th floor apartment in 2015. Her gut renovation of the four-bedroom unit resulted in what one realtor called “plenty of star power.”

But all the while the Apthorp endured internal strife and buffeting, its sublime exterior kept that all secret–a regal, unruffled presence on the Upper West Side.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

building database

Landmarks Timeline

Keep Exploring

Designation Report

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the business currently at 2211 Broadway:

Meet Joseph Lee!