The Varuna

by Tom Miller

In 1902 the Varuna Realty Corp. completed construction on a 10-story apartment building on the northeast corner of Broadway and West 80th Street. Called the Varuna, the building was designed by the well-known architect John H. Duncan in the Renaissance Revival style. Stores lined the Broadway side, while residents entered through a Classical portico at 225 West 80th Street. Stone balconies with iron railings at the fifth and eighth floors, and Beaux-Arts inspired cartouches at the top floor, gave the Varuna an air of elegance. Inside, apartments of either five or six rooms rented for between $1,000 and $1,200 per year—just over $3,000 a month today for the more expensive options.

The Varuna was managed by Robert C. McBride and his wife, Corinne. Around April 20, 1907, Corinne became ill. But, being Christian Scientists, the couple did not seek medical treatment. A few days later Corinne’s sister, Alice Chisem, visited and urged her to see a doctor. Instead, two Christian Science caretakers, Margaret Duncan and Anna C. Crowley, were called in.

Alice returned a few days later to check on her sister. The Washington Post said, “Mrs. Chisem was not satisfied with the food which Mrs. McBride was getting, which consisted of beef and clam broth and the whites of eggs. She wanted her sister to have some ochre, but Mrs. Crowley said ‘no.’” Anna Crowley told Alice that she was a non-believer and her influence was preventing Corinne McBride from recovering.

On April 27, one week after she first fell ill, Corinne McBride died of pneumonia. An inquest was held, and on May 14, the coroner’s jury found “that said death might not have taken place if proper medical attention had been furnished.” Robert McBride, and both “so-called Christian Science practitioners,” as worded by The Sun, were censured by the jury.

Also living in the Varuna in 1907 was a 20-year-old widow, Mildred Meffert. One evening that year she attended the opera, where the internationally renowned tenor Enrico Caruso spotted her from the stage. The Sun later said, “He sought an introduction and the acquaintance ripened into love. She was a guest at his castles in Italy and met his children.” On April 15, 1909, he proposed marriage, after which Mildred was introduced in Europe as “the future Signora Caruso.”

The bullet hit the millionaire in the right thigh. As he tried to flee, Lillian shot again, this bullet entering his right calf.

The two were to be married that fall, but then Caruso told her that “he could not break into his profitable opera season even for a honeymoon.” The wedding was postponed. Mildred traveled with him the following season through France, Italy, and England. The wedding was postponed again that fall, and again the following spring. It pattern continued until March 13, 1913, when Caruso simply walked out. On April 21, 1914, Mildred Meffert sued the opera star for breach of promise, asking $100,000 damages. The cost to repair her broken heart would equal about $2.8 million in 2022.

In the meantime, in May 1911, 22-year-old vaudeville singer Lillian Graham and 19-year-old Ethel Conrad moved into an apartment. Lillian had earlier been involved with millionaire William Earl Dodge Stokes, who had married Helen Blanche Ellwood in February of that year. On June 7, Ethel telephoned Stokes, telling him she had incriminating letters that she had written to Lillian. According to Stokes, “She said Miss Graham had sailed yesterday on the Baltic and I must come right away.”

When Stokes arrived at the apartment that evening, both women confronted him. Stokes later said, “Miss Graham then said she had some letters of mine, and wanted $25,000 for them…Then both women drew revolvers from their dresses at about the same time and pointed them at me.” Stokes did not believe they would shoot, laughed at the women, and made a move for the door. Lillian was the first to fire.

The bullet hit the millionaire in the right thigh. As he tried to flee, Lillian shot again, this bullet entering his right calf. Stokes grappled with Lillian for the gun. He wrested it away and held Lillian’s wrists tightly. Lillian shouted to Ethel, “Now it’s your turn. Shoot him.” Although Stokes used Lillian as a human shield, Ethel was able to shoot him in the left calf.

Still holding tight to Lillian, Stokes managed to open the apartment door and the pair spilled out into the hallway with Ethel close behind. The commotion roused the three Japanese servants of vaudeville booking agent Pat Casey, who lived across the hall. The women screamed, “He’s trying to murder us!” and all three men pounced upon Stokes and began pummeling him.

The evening ended with Lillian and Ethel, along with the three servants, being arrested and Stokes being transported to Roosevelt Hospital. (The loss of his servants was problematic for Pat Casey, who was giving a dinner party.) Tagged by newspapers as the “Shooting Showgirls,” Lillian Graham and Ethel Conrad were tried that November. Both defendants claimed that it was Stokes who initiated the meeting, demanding to have the letters back. After being found not guilty, they formed a vaudeville act together.

The year after the sensational incident, the building’s name was changed to The Hadrian. It was home to several residents who were involved in the arts. Painter Antonio del Conde lived here in 1917, as did vocal coach Thaddeus Wronski. Born in Poland, Wronski temporarily closed his Phono-Art-Vocal-Studios in his apartment that year. With World War I raging, he turned his attentions to his homeland. His explained in an announcement in Musical America on October 20 that “owing to his work connected with the recruiting campaign for the Polish Army now being organized in the country,” the studio would close until further notice.

Another musical resident was Giuseppe De Luca, the Italian baritone of the Metropolitan Opera. The conductor Arturo Toscanini reportedly called him “absolutely the best baritone I ever heard.” The world-wide influenza pandemic of 1918 struck the De Luca apartment when Olympia De Lucca, the singer’s wife, became ill on October 18, 1918. Her condition devolved into pneumonia, and ten days later, on October 28, she died.

The C & L Lunchroom occupied the commercial space at 2246 Broadway at the time. In June 1919 Charles Arthur was hired as a dishwasher. The young Black man was from the West Indies and was, perhaps, unaware of the widespread racism throughout America. At any rate, he almost immediately was attracted to Irma Dale Scholtzhauer, a white waitress. She ignored his advances for two weeks, until on June 28, his patience ended. A few minutes after she had turned down his request “to make a private appointment with him,” as worded by The Sun, she took a second tray of dishes into the kitchen, “and he annoyed her again.”

The Sun reported, “She paid no attention and as she was walking back to one of her table the enraged black stepped out of his compartment and fired a shot with a .38 calibre revolver.” Irma fell dead to the floor. At the station house Arthur calmly explained that he had decided that if she “again repulsed his attentions to take her life.”

A colorful if tragic, resident arrived in the fall of 1920. Lady Lillian Maxwell-Willshire’s husband was the seventh Baron Willshire. World War I had depleted the Willshire fortune, the ancestral estates in Sussex, England were mortgaged, and now Lady Lillian arrived in America to try to make a living. She told the New York Herald in her Hadrian apartment, “My automobiles have been sold in London and except for a few family jewels which once belonged to my mother, I arrived in New York penniless. I pawned some of the jewels in order to rent this apartment and I have clothes enough to last me for at least a year.” In what must have been a humiliating drop in her social status, she stepped onto the American stage on the night of November 29, 1920, “as the principal wife in the harem scene of ‘Afgar’ at the Central Theatre,” reported the New York Herald.

She ignored his advances for two weeks, until on June 28, his patience ended.

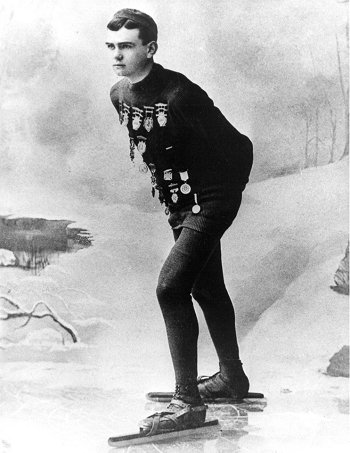

A celebrity of sorts who lived in the Hadrian at the time was former world championship skater Joseph F. Donaghue. Born in 1871, he was only 16 years old when he won his first skating championship. The New York Herald noted, “His greatest feat was the winning of the 100-mile race at Stamford, Conn. in 1893. His time, which clipped four hours from the previous record, was seven hours and eleven minutes.” Sadly, his greatest triumph was also the end of his career. “The race permanently injured his health, and he soon after gave up competition,” said the newspaper. The 50-year-old bachelor died on April 2, 1921.

The stores along Broadway were occupied by a wide variety of businesses over the decades. But none played a more important part in American socio-political history than did Broadway Baby in 1979. The chic infant and toddler boutique was managed by Bernardine Dohrn, who was secretly a member of the Weather Underground, the radical political group also known as the Weathermen. Working on behalf of the Black Liberation Army, she would duplicate clients’ credit and ID cards, which were then used to rent vehicles to be used in armed robberies.

The scheme collapsed in 1981 when arrests were made in the famous (and failed) Brink’s armored car robbery in Nyack, New York. The identifications used to rent the car and several others led back to Broadway Baby and Bernardine Dohrn. She refused to testify or give handwriting samples to the grand jury, earning herself seven months in jail.

The oldest store on the row is the bookshop in the northern space. It opened as the Gryphon Bookshop around 1989 and was described in the 2002 An Actor Prepares to Live In New York City as being “packed solid with cheap, mostly used and rare paperbacks and hardcovers.” The name changed to Westsider Rare & Used Books around 2006 and it remains in the space.

Although the balconies lost their railings sometime before mid-century, John C. Duncan’s handsome design is little changed since The Varuna opened its doors in 1902.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

Building Database

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the local business currently at 2244 Broadway:

Meet Robert Beck!

Meet Shiry Allal!