2276 Broadway

by Tom Miller

On October 24, 1887, what the Real Estate Record & Guide described as “the splendid plot of four lots on the southeast corner of the Boulevard and 82d street” were sold at auction. (The Boulevard would be renamed Broadway in 1900.) They were sold three more times before developer F. F. Smith announced he had hired architect J. Averit Webster to design four five-story “flat and store” buildings on the site. Completed the following year, the brick-faced structures were trimmed in brownstone and designed in the neo-Grec style. Although otherwise identical to its neighbors, the corner building was slightly wider, at 27-feet. And unlike the others, its residential entrance was not on Broadway, but around the corner at 230 West 82nd Street.

Among the most colorful of the original tenants was attorney Henry Clay Stephens. He and his wife had a son, Victor. On November 1, 1893, Mrs. Stephens hired a live-in dressmaker, Florence McFeely. A few months later Mrs. Stephens traveled to the South for a visit, and the 27-year-old dressmaker “remained for a few days and departed,” according to the New York Herald. Upon Mrs. Stephens’s return, said the article, “she missed $50 worth of dresses and $15 in cash. Mrs. McFeely was suspected.” On May 20, 1984, Stephens had McFeely arrested. But her story was far different from his.

The indignant dressmaker told the court that Stephens was “a rabid spiritualist” who “believed himself to be the reincarnation of the prophet Isaiah and that his son, Victor, was the living prototype of Jonathan, the friend of David.” She went on to testify that Stephens would rise at 2:00 in the morning, “and spend hours gesticulating and muttering incantations, and because she would not accept his self-constituted title, he had been unkind in his treatment of her.”

The World reported, “Attorney H. Clay Stephens, of No. 230 West Eighty-second street, says that he has learned the secret of keeping perfectly healthy without drugs of physicians, and claims to be able to heal others.”

A year later Henry Clay Stephens appeared in the newspapers for another bizarre reason. On April 17, 1895, The World reported, “Attorney H. Clay Stephens, of No. 230 West Eighty-second street, says that he has learned the secret of keeping perfectly healthy without drugs of physicians, and claims to be able to heal others.” Stephens sent out circulars announcing his intentions to establish the New York City Healing Institute for Body, Mind, and Soul, “if sufficient interest was manifested.” A meeting was held in his apartment on April 16. “A goodly number attended, and the interest shown presages the establishment of the institute,” said The World. (Despite the newspaper’s prediction, it does not appear that the institute was ever launched.)

At the turn of the century, the Broadway store space was home to the McCracken & Madill “liquor saloon,” operated by Irishmen John A. McCracken and James Madill. It remained there until July 1910 when the men declared bankruptcy.

In the meantime, the residents of the apartments continued to be upper-middle class, like the architectural sculptor, James M. Kerr, here in 1902.

Change came in May 1920 when the Childs Company leased the building for what The Sun described as “a long term of years.” Formally organized in 1906, the firm operated a chain of “casual luncheon restaurants.” The company was perhaps as well known for its architecture as for its food. And the Victorian façade of 2276 Broadway was now outdated and most definitely not reflective of a Childs’ Restaurant.

In 1923 Rider’s New York City, A Guide-Book for Travelers, commented on the Childs’ Restaurants, including this one. The critic said the chain “have set a standard in the way of sanitary service and quality. Childs’ prices are, however, no longer as reasonable as those of other ‘chain’ restaurants in its class.”

In 1937, following the end of Prohibition, the Childs’ Restaurant at this address acquired a liquor license from the state. That same year it was the victim of what the press had nicknamed “the woman in black.” The fashionably dressed woman had been terrorizing restaurant owners on the Upper West Side, walking up to the cashier, quietly displaying a nickel-plated handgun, and making off with cash from the register.

At 3:00 on the morning of February 11, 1937, a female wearing a black dress and carrying a black leather bag, entered the restaurant. Sitting in a booth and eating breakfast was a uniformed police officer, Adam G. MacKenzie. The cool robber bought two packs of cigarettes from the cashier, Albert Swank, then showed him her gun and quietly demanded the money from the register. The New York Sun reported, “He gave her $20 and she walked out, making her escape in a taxicab.”

The cool robber bought two packs of cigarettes from the cashier, Albert Swank, then showed him her gun and quietly demanded the money from the register.

As soon as she was out the door, the cashier yelled that he had been robbed. Officer MacKenzie bolted after her, and “commandeered another taxicab to chase the holdup woman,” said the article. The pursuit ended at 84th Street when the first cab became lost in traffic.

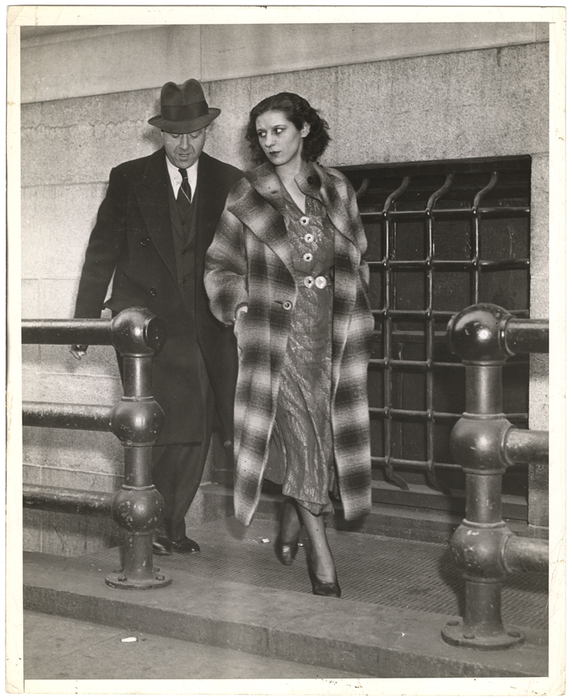

Nellie Gutoswwky, who was just 21 years old and went by the alias Norma Parker, was finally caught on February 26. She was indicted for several robberies, including the Childs’ Restaurant heist. Ironically, the Syracuse American reported, “When arrested she was ‘armed’ with a cap pistol.”

In 1944 the restaurant space became home to the Salem Hosiery Store. Like rubber, butter, and other scarce wartime commodities, the sale of nylons was strictly regulated by the Office of Price Administration. The store’s owner, Braham Meyer Salem, got in trouble with the OPA for selling nylon stockings “above ceiling prices,” according to The New York Sun on May 6 that year.

From 1979 to 1991 the store was occupied by West Town House, an all-inclusive home furnishings shop. It offered everything from large furniture to bathroom accessories. An advertisement in New York Magazine on October 8, 1979, said, “In fact, you’ll find all you need for your apartment, except of course the kitchen sink.” The store was replaced by Laytner’s Linens, which remains in the space today.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

Building Database

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the business at 2276 Broadway: