La Riviera

by Tom Miller

J. C. Burne acted as both architect and real estate developer when he planned an apartment building at the southeast corner of Broadway and 99th Street just before the turn of the last century. Above the two-story stone base, five stories of beige brick were trimmed in terra cotta. His Renaissance Revival design included elaborate Italian-style pediments over certain openings. Burne placed the entrance at 230 West 99th Street within a stately portico upheld by paired columns.

Called La Riviera, its apartments contained eight “very large, sunny rooms,” according to an advertisement. They rented for $1,000 per year, or about $2,858 per month in 2023. The residents ranged from businessmen—like Louis Heidenheimer, who owned a hops business on South William Street—to artists and musicians, like soprano Ethel Crane and organist and composer Charles B. Hawley.

The widely talented Hawley was born in Brookfield, Connecticut and began playing the church organ there when he was 12 years old. By the time he moved into La Riviera, he was the music director and solo basso at the Broadway Tabernacle Church. In addition, he was a vocal instructor and composer, having written popular songs like “Spring’s Awakening,” “Ah! ‘tis a Dream,” and “The Sweetest Flower that Blows.”

A resident had a near brush with death on February 23, 1904. Mrs. Virginia Ree, who was 83 years old, attempted to cross Sixth Avenue at 21st Street that afternoon “when the crowd of home going shoppers was thickest,” according to The Sun. Just then, a horse pulling a butcher’s wagon got spooked and galloped down the avenue directly toward Virginia. The newspaper said, “To avoid the runaway she started across the car tracks and was run down by a northbound car.” Happily, the elderly woman suffered only a fractured leg.

Two months later, another resident, Mrs. Vienna Gano, found herself in serious legal trouble. A Christian Scientist, Mrs. Gano accepted “patients” whom she would cure by faith. Among them was actress Loretta Young, who came with a disturbing problem. She was engaged to be married to actor Earl Dewey in May and, in mid-April, had undergone an operation performed by Dr. Charles M. Tobynne. The police became involved when Young died on April 20. It appears, since both Tobynne and his nurse were arrested that the procedure had been an abortion. The New York Times reported, “a subpoena was issued for Mrs. Vienna Gao of La Riviera Apartments, 230 West Ninety-ninth Street, a Christian Scientist, to whom Miss Young had applied for treatment, but who, according to Detective Short, stated that she had abandoned Miss Young’s case because the actress lacked faith.”

Her bill totaled $900 (nearly $29,000 today).

Another early resident was James Curran, president of the James Curran Manufacturing Company. Born in 1841, he was a veteran of the Civil War. According to the Building Trades Employers’ Association Bulletin in December 1905, “For the past forty years he was actively engaged in the business of steam heating, having installed the steam heating plans in many of the public and large office and commercial buildings in this city.”

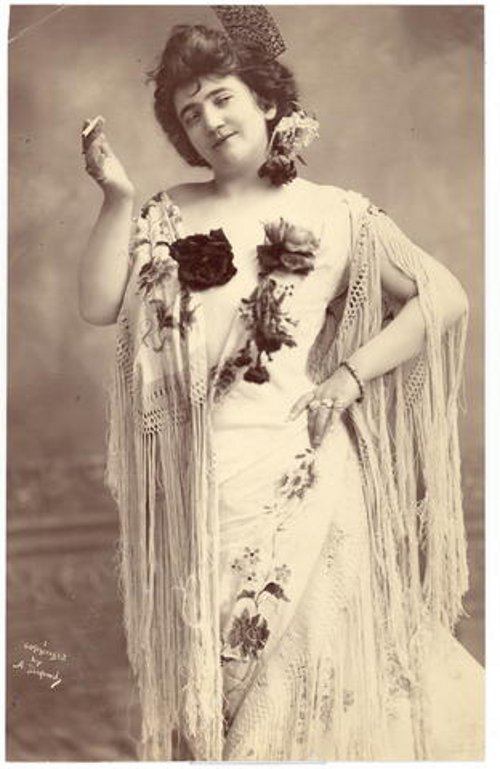

Actress and singer Bertha Shalek lived in La Riviera by 1908. Born in Chicago on January 2, 1884, she first appeared on stage “as a violinist,” according to the 1908 Who’s Who on the Stage. Her debut in the title role of Carmen came in 1903 at the Providence Opera House. The article noted that in the fall season of 1907, “she was with the Van den Berg Opera Company at the West End Theatre, New York.”

Joan Schon, who also lived here that year, was marginally involved in the theater. She was a masseuse, and among her well-known clients was opera star Emma Calve. Their relationship was both professional and social. The New York Press said on January 9, 1908, “Miss Schon is a great friend of Calve.”

When Joan’s dentist, Dr. Allison W. Harland, discovered the friendship, he sought to profit from it. The Sun explained, “he felt he would get the singer as a customer if Miss Schon would recommend him.” Joan considered the request and said she would speak to Madame Calve. The newspaper added, “But, I will not do that for a song. I must get something out of it,” Dr. Harlan promised Joan Schon he would give her one-third of any bill paid by Calve.

On March 17, 1907, acting on Schon’s recommendation, the diva visited Dr. Harlan’s office. Her bill totaled $900 (nearly $29,000 today). The Sun said that Madame Calve was “so pleased with the work that she paid without a murmur. She told her friend Joan about it.” And Joan next visited the dentist. He told her that “it would be a breach of professional ethics for him to pay for even friendly “touting.” And so, the dentist and the masseuse ended up in court.

The building’s most colorful resident was Professor W. Bert Reese, a mentalist who had appeared, according to him, before several crowned heads of Europe. Around the time of Joan Schon’s lawsuit, he visited Thomas A. Edison uninvited and, according to the inventor, “gave him information which he lacked, concerning certain ingredients needful in his storage batteries.” The two men had never met. Later, Edison sent a telegraph to Dr. W. H. Thomson, which read, “See Prof. W. Bert Reese, 230 West Ninety-ninth Street, New York City.” The New York Times recalled on November 13, 1910, “Dr. Thomson tested him and found him genuine. Being a fair-minded man, he wrote at once to Mr. Edison and told him that the mind reader, or whatever he may be, had done extraordinary things.”

Reese would be tested again in January 1913. An undercover female detective appeared at his apartment, “representing herself as a single woman burdened with wealth and real estate, but trouble far more by her inability to attract mankind,” said The New York Times on January 18. He advised her not to sell her real estate, saying he thought it would “increase twofold in value, owing to the election of a Democratic President.” Although he refused payment of any kind, she arrested him for fortune telling.

At the station house, detectives poked fun at the 62-year-old. Eventually, Reese asked one, Detective Sussillio, “to write down on a piece of paper any question he desired answered,” said The New York Times. Sussillio wrote down his question, showed it to another detective, and folded it away.

“You have asked me to tell you the first name of your mother. Her first name is Pauline,” said Reese.

He had gotten the question and the answer correct.

In Night Court, Magistrate Krotel questioned the female detective. The New York Times reported, “after learning that she had put false questions to Reese told her she could not complain at receiving false answers.” Reese was released.

He was not so lucky two years later when another undercover detective came to his apartment. This time, he accepted five dollars from Adele Priess. Although he pleaded in court, “No, I am not a low fortune teller, I’m an entertainer. I have entertained James J. Hill, William Travers Jerome and Charles Dillingham. The crowned heads…” He was cut off at that point by the Magistrate, who asked whether he had accepted the five dollars.

Although he refused payment of any kind, she arrested him for fortune telling.

“That was just part of the entertainment,” Reese responded.

He was released under $1,000 bond and ordered “not to entertain that way for a year.”

The Reeses were still living here in 1926 when W. Bert Reese died in Europe. His widow continued to live in their apartment.

By 1913, Lucille Dreyfous and Florence Dreyfous, lived here. The 45-year-old Florence was an artist who exhibited two watercolors, A Boy and Mildred, in the landmark International Exhibition of Modern Art that year. She had studied at the Chase School of Art and under Robert Henri at the Henri School of Art. The Brooklyn Museum of Art included her work in its 1921 watercolor exhibition.

On the night of June 1, 1920, a burglar entered the apartment of Gilbert Kuh and his wife by shimmying up the dumb water. He made off with “jewelry and wearing apparel valued at several hundred dollars,” according to the New-York Tribune. Working on the statement from the building’s janitor that he saw the crook stashing “part of the loot in the courtyard of the building,” a detective hid in the courtyard. The plan worked. Before dawn, the thief returned to recover his booty. John Buckley, a 29-year-old tile-layer, was arrested but denied any knowledge of the crime.

Three weeks after the incident, the New-York Tribune reported that La Riviera had been leased to the West Ninety-ninth Street Corporation for 84 years. The article noted “The lessees have filed plans for extensive alterations…including the remodeling of the ground floor into stores.” The renovations resulted in three stores on the Broadway side.

In 1954, the corner store was home to the office of optometrist Murray M. Smolar. Appropriately, today, a branch of Cohen’s Fashion Optical occupies the space. Coincidentally, 2616 Broadway, which was the Hong Liquor Store in the third quarter of the 20th century, today houses Cork & Barrel, another liquor store.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

BUILDING DATABASE

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the businesses at 230 West 99th Street aka 2616-2618 Broadway: