The Magnolia

by Tom Miller

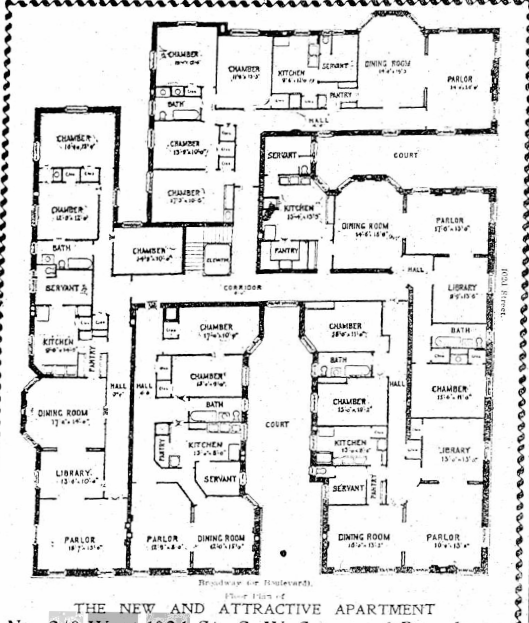

In November 1898, the architectural firm of Neville & Bagge filed plans for a “six story brick flat” on the southwest corner of the Boulevard (soon to be renamed Broadway) and 102nd Street for developer David R. Todd. Completed the following year at a cost of $300,000, the Magnolia’s tripartite design included a single-story base with alternating rows of brick and limestone that created a striped effect, an understated four-story midsection, and sitting above a prominent cornice, an ebullient sixth floor, where the openings were edged in stone quoins and wore sunburst-like voussoirs.

Tenants could choose from apartments of six, seven, or eight rooms. An advertisement touted the “highest ceilings and widest private halls on the West Side. Finish high class. Every convenience with first-class service.”

The residents were, expectedly, well-to-do and professional. Among the first were attorney Daniel O’Connell and his wife, and broker Frank S. Williams and his wife. Virginie Tegetmeier moved into the building with her children following her divorce from Alfred Tegetmeier in March 1902. On May 15, 1900, Virginie appeared before Justice Hascall in the City Court, requesting to legally change her surname and those of her children back to her maiden name, Bertrand. She explained that Tegetmeier “was difficult to spell and pronounce, and it subjected her children to much embarrassment,” according to The New York Times. But it seems that Virginie’s mother had a great deal to do with the decision. “Moreover, the children’s grandmother, she said, promised to make them her heirs if they took the name of Bertrand.”

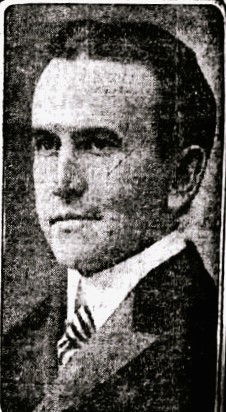

In 1903, the Magnolia received a rather celebrated resident in Dr. Samuel Gately Tracy. Born in New York City in 1867, Tracy received his medical degree at Bellevue Hospital Medical College in 1890. He was a pioneer in work on electricity and radium and wrote frequently on medical issues.

The Tracy apartment was burglarized in the autumn of 1907, and it appeared to be an inside job. An advertisement in The New York Times on September 11 read: “A reward paid, no questions asked, for return of silver-plated ware and clothing taken from doctor’s apartment, 240 West 102d St.”

Tracy’s experiments with electricity prompted him to announce in 1908, as reported by the Chicago Tribune, “that old age could be retarded by using ‘high frequency’ electric currents.” A year later, on May 31, 1909, he published a paper in which he revealed that “many cases of dyspepsia are due to an irritated brain center and that such cases could be relieved by the use of high frequency currents.”

In leaving Pittsburgh, he had neglected to pay this $2,700 hotel bill—equal to $85,800 in 2023 terms.

His further experiments led Dr. Samuel G. Tracy to establish the Health and Longevity Club, which held its meetings in his apartment. On April 19, 1911, The World reported that during the previous evening’s meeting, he said, “There is no doubt that humanity, through understanding the causes of old age and the proper care and preservation of the functions of the body, will, in the future, greatly extend the span of human life.” The New-York Tribune quoted him as saying, “The normal age of a man ought to be 125 years instead of the psalmists’ three score and ten.”

Living here in 1910 was 61-year-old Maurice T. Lane. The New York Times described him as “a small man with a gray mustache, and looks prosperous.” The newspaper quoted police as saying he “is well known to art connoisseurs throughout the world, and who formerly owned many valuable art treasures.” The widower shared his apartment with his three daughters.

In October 1910, Lane traveled to Pittsburgh to sell “works of art, including paintings and tapestries,” according to The New York Times. He took a suite of rooms in the Lamont Hotel there, where he lived “in great style” for eight months. But things did not go as he had hoped. The newspaper said, “A number of Pittsburgh millionaires to whom he hoped to sell art treasures did not care for his wares.” He left Pittsburgh on June 7, 1911, and returned to the Magnolia.

Then, late on the night of July 18, police knocked on the door and arrested Maurice T. Lane. In leaving Pittsburgh, he had neglected to pay this $2,700 hotel bill—equal to $85,800 in 2023 terms. The New York Times reported, “He was locked up in Police Headquarters, charged with being a fugitive from justice.”

In the meantime, the names of the socialite residents of the Magnolia appeared in newspapers for their entertainments. On February 11, 1912, The New York Times reported, “Mr. and Mrs. Alfred Son…will give a theatre party, followed by a supper and dance in their home, on Saturday evening.” On December 27, 1912, Mrs. H. C. Rogers gave a dance at the Hotel Astor for her debutante daughter Helen. The New York Times reported, “There were about 400 young people on the floor.” And on March 23, 1913, the newspaper said, “Mrs. John F. McCauley of 240 West 102d Street gave a daffodil dinner on Friday for Miss Stella Boyd of Winnipeg.”

All the residents, of course, had at least one servant. Cigar manufacturer Sigmund Strauss and his wife hired a new maid, Rosa Decissey, in 1913. A few months later, on the evening of September 17, Mrs. Strauss was doing needlework in the parlor, and asked Rosa to fetch a needle. When she did not return, Mrs. Strauss went to the next room to see what the problem was. The New York Times reported, “The room was in darkness, and she switched on the electric light just in time to see the maid climbing out on the still of the window looking down on Broadway. The woman was balancing on the ledge when Mrs. Strauss’s arms closed around her waist.”

Mrs. Strauss then let out a scream—described by the newspaper as being half fear and half a cry for help “that could be heard a block away.” As she looked down, she was relieved to see first a few, then dozens of people gathering on the street looking up. But none of them seemed to be eager to help, just to take in the dramatic scene. “Up there at a window of the Magnolia apartments they could see mistress and maid struggling. The larger woman seemed to overhang the sidewalk, twisting and wrenching to free herself, the woman of slighter build hanging on grimly, and both uttering piercing screams.”

The struggle continued for 15 minutes until, finally, a policeman named O’Neil saw what was transpiring. As he rushed into the Magnolia’s lobby, he was joined by two more. Just as it seemed to Mrs. Strauss that she could hold on no longer, the police crashed through the apartment door. “She had a confused feeling of a dozen huge arms reaching over and past her and closing about her burden,” reported The New York Times. At that point, Mrs. Strauss dropped unconscious to the carpet.

The doctor who arrived from Knickerbocker Hospital discovered he not only had a patient in Rosa Decissey, whom he diagnosed with melancholia and ordered taken away in an ambulance, but “in Mrs. Strauss, who was on the verge of hysteria.”

Dr. Samuel G. Tracy never married. At some point, his sister, Martha M. Tracy Cleland, the widow of Dr. Thomas J. Cleland, moved into his apartment. She died here at the age of 83 on February 3, 1941. Her funeral was held in the apartment three days later. There would be a second funeral in the Tracy apartment the following year. On December 8, 1942, The New York Sun reported, “A funeral service for Dr. Samuel G. Tracy, one of the founders of the Bloomingdale Clinic…will be held tomorrow at his home, 240 West 102d street.” Tracy was 75 years old.

City engineers peered into the hole with a remote camera, and discovered an intact room of Libby’s Hotel—complete with furniture and bookcases.

A colorful resident was Max Bernstein, whose wife Sarah had died in 1924. Born in Russia in 1891, he came to America at the age of 12 and began working in a restaurant. A year later, his mother, Libby, died. The teen “conceived the idea of a hotel in her memory,” The New York Times later recalled. Bernstein saved his money until he had $75, with which he opened a tiny candy store on the Lower East Side. The New York Times said, “he worked it up to a lunch car, then a small restaurant, then a big restaurant, and so on.” Each of his businesses was named Libby’s.

By 1926 Max Bernstein had amassed a fortune. That year he began construction of his $3 million Libby’s Hotel and Baths at the corner of Chrystie and Delancy Streets. The New York Times described it as “unique in that it was a twelve-story, steel-constructed edifice in a congested slum area with a preponderant Jewish population, [which] catered especially to a Jewish clientele through a strictly Kosher commissariat.” It boasted a swimming pool, lounges, and what The New York Times called “the most luxurious Turkish and Russian baths in this country.”

Only three years later, the Libby was demolished by the city for the widening of Chrystie Street. As an interesting side note, in 2001, a sinkhole opened at the corner of Chrystie and Delancey Streets. It grew so large that trees and buildings were threatened. City engineers peered into the hole with a remote camera, and discovered an intact room of Libby’s Hotel—complete with furniture and bookcases. The New York Times quoted Parks Commissioner Henry J. Stern as saying, “It reminds me of Pompeii.” Astonishingly, no one attempted to explore the room. It was simply filled in and the sinkhole paved over.

Max Bernstein died in his Magnolia apartment on December 13, 1946. The New York Times recalled, “Mr. Bernstein also tried other business ventures during an exceptionally colorful career. He was at one-time proprietor of a theatrical magazine, and had lately been in the realty business.” Max Bernstein was 57 years old.

As a child in the 1960s, Suzanne Vega and her family lived at 240 West 82nd Street. She attained prominence in the mid-1980s as a singer-songwriter in Greenwich Village clubs. By the 1990s, she was internationally known.

The building was converted to a cooperative in 1984.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

BUILDING DATABASE

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the businesses at 240 West 102nd Street aka 2669-2675 Broadway:

Meet Christopher Barnes!