The Sweet William

by Tom Miller

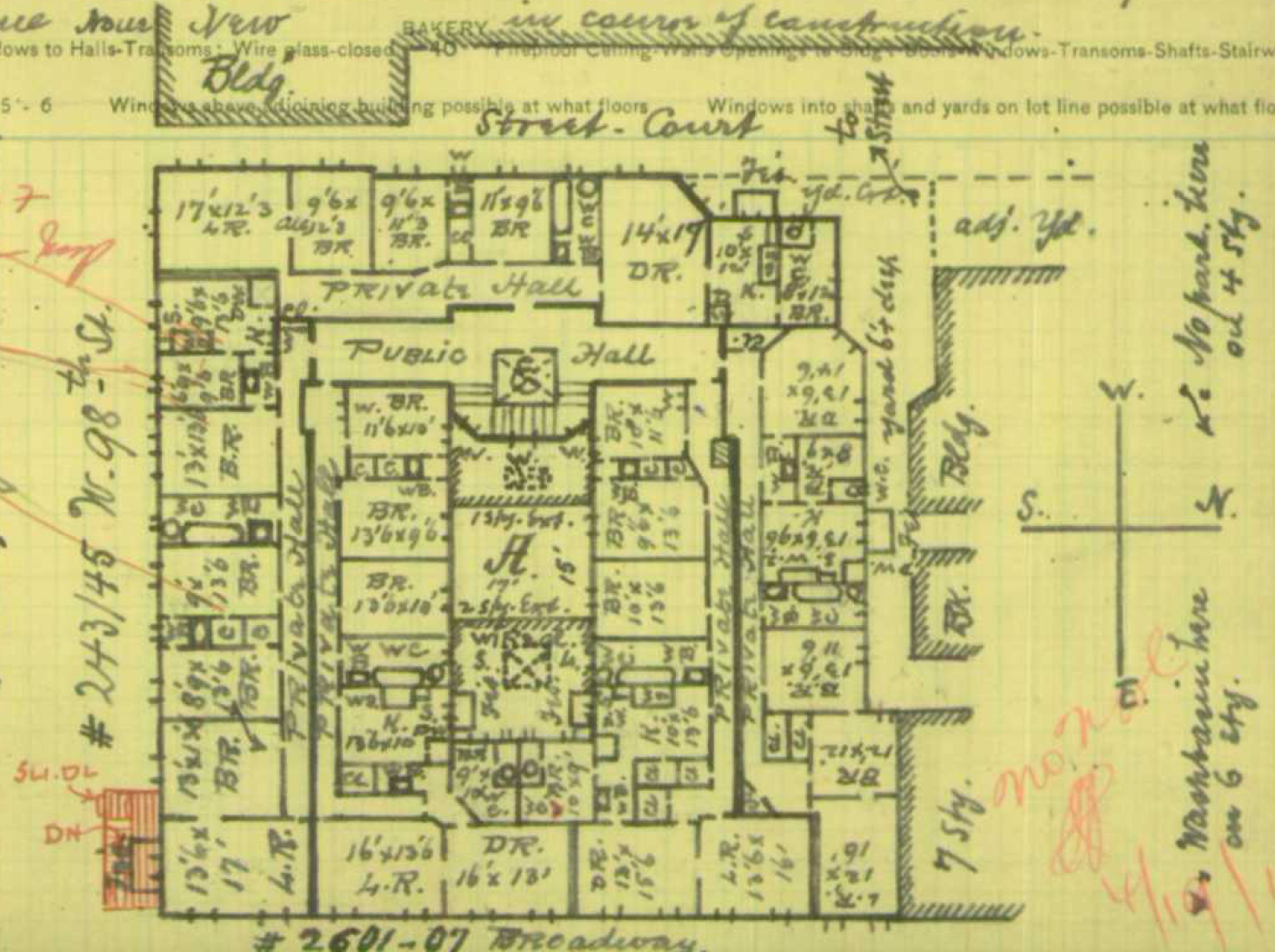

On June 9, 1899, the architectural firm of Neville & Bagge filed plans for a seven-story apartment house on the northwest corner of Broadway and 98th Street for developer Emilio Vigna. Completed early in 1900, the Sweet William, as it would be known, cost $225,000 to construct—more than 8 million in 2023 dollars.

The building’s tripartite, Renaissance Revival design sits upon a two-story rusticated limestone base. The upper sections are defined by intermediate cornices. Here the beige brick façade is decorated with limestone, Renaissance-inspired motifs like balconies—both faux and real—and intricately carved panels. The impressive entrance is located on the side street, while the Broadway elevation houses stores.

On September 25, 1904, the New York Herald reported, “Mrs. Arthur Elliot Fish…has taken a pretty apartment in the Sweet William, No. 243 West Ninety-eighth street. Although her health during the entire summer has been a source of grave concern to her many friends, Mrs. Fish assumed charge of the children of the Free Industrial School for Crippled Children at the summer home in Warren Mass., her only rest being a fortnight spent with friends in Vermont.”

Mrs. Arthur Elliot Fish would be the Sweet William’s most visible resident for many years. Aside from her social prominence, she was well-known for her work with handicapped children. She founded the Free Industrial School for Crippled Children of the Poor in 1898, laying the cornerstone of its building on West 57th Street the following year in memory of her only son, Gilbert Austin Fish, who had died at 16. By the time she moved into the Sweet William, the school had operated a Country Home and grounds in Claverack, New York. The administration of the two locations nearly monopolized the wealthy widow’s time.

Among Mrs. Fish’s neighbors in the building in 1915 were Clifford G. Pearce and his wife Blanche. The couple had one live-in servant. On the evening of August 24 that year, the Pearces were sitting in their parlor when Blanche heard the dining room door shut. Thinking perhaps a breeze from an open window had blown it, she investigated. The New York Times reported, “She went to see and discovered a man bending over a desk in her room.” Blanche screamed, which brought Clarence running from the parlor and sent the thief bounding out the window and down the fire escape. Pearce followed close behind while Blanch leaned far out a window and, according to The Sun, “screamed over and over again.”

Aside from her social prominence, she was well-known for her work with handicapped children.

The New York Times reported, “Heads appeared at various windows, and the burglar ran the gauntlet of dozens of eyes as he scrambled for the ground.” Also hearing Blanches screams was a hallboy, Thomas Shaw. Seeing the man descending the fire escape, he grabbed an iron bar and waited at the bottom. The New York Times recounted, “As the burglar dropped fifteen feet from the lower fire escape to the pavement of the court [Shaw] brought the bar down on his head with a blow which felled the man. He wore a Panama hat, and this broke the blow so that he was not stunned.”

The robber got to his feet and ran, followed by Thomas Shaw and Clarence Pearce. As they ran, Shaw and Pearce yelled, “Stop, thief!” according to The Sun, “Broadway strollers took up the cry and joined in the chase, while storekeepers went to their doors and blew police whistles.” The crowd ran through traffic, dodging “the thronging automobiles” until the crook reached Riverside Park, where he vaulted over the stone wall to the park and dashed south. It was then that Patrolman Seeger joined the chase. He was fresh, and the burglar was not. Out of breath, 19-year-old Joseph Allen was quickly captured. Blanche Pearce identified a silver vanity box, a gold bracelet, and a leather purse found on his person as her property. And Thomas Shaw “identified a dented Panama hat as the one his iron rod had descended upon,” said The Sun.

Godfrey Goldmark was also living in the building at the time, an attorney and 1902 graduate of Cornell University. On January 1, 1916, the 34-year-old was appointed secretary to the Chairman of the New York State Public Service Commission. The following year, in June, he was made assistant counsel of the Commission, earning $4,000 per year.

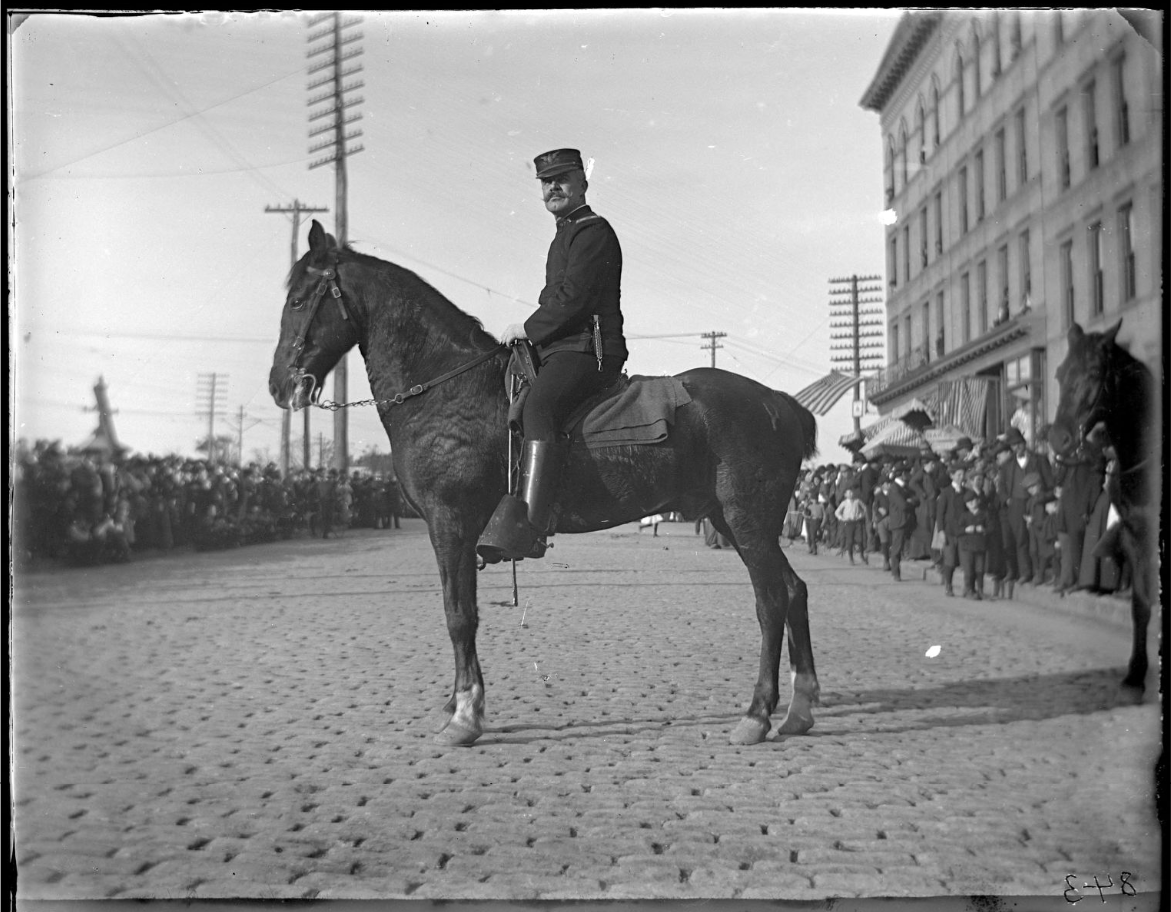

A colorful resident was Colonel Nathaniel Blunt Thurston. He had been a member of the Seventy-Fourth New York Infantry since around 1877 and was commissioned a lieutenant colonel in 1898, just prior to the start of the Spanish-American War. After the war, he was appointed First Deputy Police Commissioner by Mayor Seth Low on January 1, 1902, but resigned the following October to again devote his career to the military.

In 1916, Thurston was deployed to McAllen, Texas, to command a border camp. His wife remained in their apartment here. When he became ill in September, he returned but soon went back to his command—too quickly, some would later surmise.

On January 17, 1917, the New York Herald remarked, “Colonel Thurston, who was affectionately known among his fellow officers and throughout the National Guard as ‘Peggy’ Thurston, had been in failing health for several months.” The 59-year-old attended a testimonial dinner on January 16. When he returned home to camp at 8:00, he complained of feeling ill. He suffered a fatal stroke three hours later. The New York Herald reported, “General O’Ryan said yesterday that he would confer with Mrs. Thurston and would announce later at division headquarters arrangements for a military funeral.”

Had he survived, Colonel Thurston would most likely have seen action during World War I, like several other residents of the building. On April 24, 1918, The New York Clipper reported, “Of twenty-six draftees to be sent to Camp Upton, April 30, as the quota of Board No. 158, twenty-five per cent are allied with the stage.” Among them was George B. Neale, a “musician and pianist,” who lived here.

Arthur Knowlson, who worked in the advertising department of The Sun, and his wife lived here on February 26, 1918, when they said goodbye to their 23-year-old son, William, as he went off to war. Tragically, on September 28 that year, The Sun began an article saying, “A War Department telegram brought to Mr. and Mrs. Arthur Knowlson, 243 West Ninety-eighth street, last night word of the death of their son, Corporal William Glore Knowlson of the 302d Engineers, who was killed August 28 while fighting with the American forces on the Vesle [River].” Corporal Knowlson was 23 years old.

In the early 1920s, the John E. Thomas pharmacy occupied 2601 Broadway, while Mugurdick J. Tashjian operated his Turkish rug and antiques shop at 2605 Broadway. Living in America seems to have exposed his wife to female independence. On September 23, 1920, The Sun reported, “The destruction of her new fall bonnet was the straw which broke the back of Mrs. Mugurdick J. Tashjian’s married life. After her husband had smashed the new hat, she says, she and her mother departed from the Tashjian apartment…and she has since lived apart from her husband.” In court, Mugurdick denied his wife’s accusations of cruelty.

Charles Leverett Hayden and his wife, the former Marjorie Grace Whitney, who had an apartment here and a summer home at Alexandria Bay, Thousand Island, also had marital problems. In court on August 7, 1922, Marjorie charged that “almost from the day they were married,” Charles was abusive. “He would be intoxicated for a week or ten days at a time at intervals of two or three weeks,” she told the judge. She said he “struck her in the face, swore and cursed her,” and that once, “he sat at the dining table of their villa on Hayden Island with a .45 caliber automatic pistol at his side and threatened ‘to shoot up everybody on the island.’”

A far-left radical activist and former member of the Weather Underground, she was the getaway driver in the notorious Brink’s armored truck robbery in Nanuet, New York, on October 20 that year.

By the mid-1930s, the once-elegant apartment building was being operated as furnished rooms. The Great Depression snuffed out hope for thousands of Americans, including Rudolph Redlin, who had been a wireless operator on steamships. He lost his job on the vessel Willett in November 1934 and two years later was still unemployed. In January 1937, he took a furnished room on the sixth floor here. A week later, on February 1, The New York Times reported that he had jumped to his death from his window.

Eight years later, on January 2, 1945, Moe Zucker stepped out of his vegetable and food store at 2603 Broadway and happened to look up. The New York Sun reported that he yelled, “Look out!” The article continued, “Many persons ran, including a woman with a baby carriage and an Army captain, and others darted into doorways, but none looked up as a woman’s body hurtled from the roof of the seven-story building at 243 West 98th street.” Irma Spitzer had recently lost her husband. The 60-year-old did not live here, but had simply come to visit her nephew, Charles Presier, who told police she had been “brooding” over her husband’s death.

The history of tragedies continued on August 10, 1975, when 30-year-old resident Ada Angeli gave a party in her fourth-floor apartment. A “dispute,” as described by police, arose and Ada was fatally shot.

Like Mrs. Arthur Elliot Fish, Judith Alice Clark was the most well-known of the residents in 1981, but for a far different reason. A far-left radical activist and former member of the Weather Underground, she was the getaway driver in the notorious Brink’s armored truck robbery in Nanuet, New York, on October 20 that year. One guard was killed, and another was seriously injured in the heist, and then two Nyack police officers were killed in the ensuing gun battle. Clark was sentenced to three consecutive 25-year-to-life sentences but was released on May 10, 2019.

Interior renovations were made in the early 2000s. Among the building’s more recent celebrated residents was actor and singer Brian Stokes Mitchell, who lived here in 2006.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

BUILDING DATABASE

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the businesses at 2601-2607 Broadway: