The Metropolitan

by Tom Miller

Real Estate developer William J. Merritt often acted as his own architect, designing rows of middle-class homes on the Upper West Side in the late 19th century. But when he planned an apartment building on the southwest corner of the Boulevard (later Broadway) and 88th Street in 1895, he turned to an established architectural firm, Little & O’Connor, to design it.

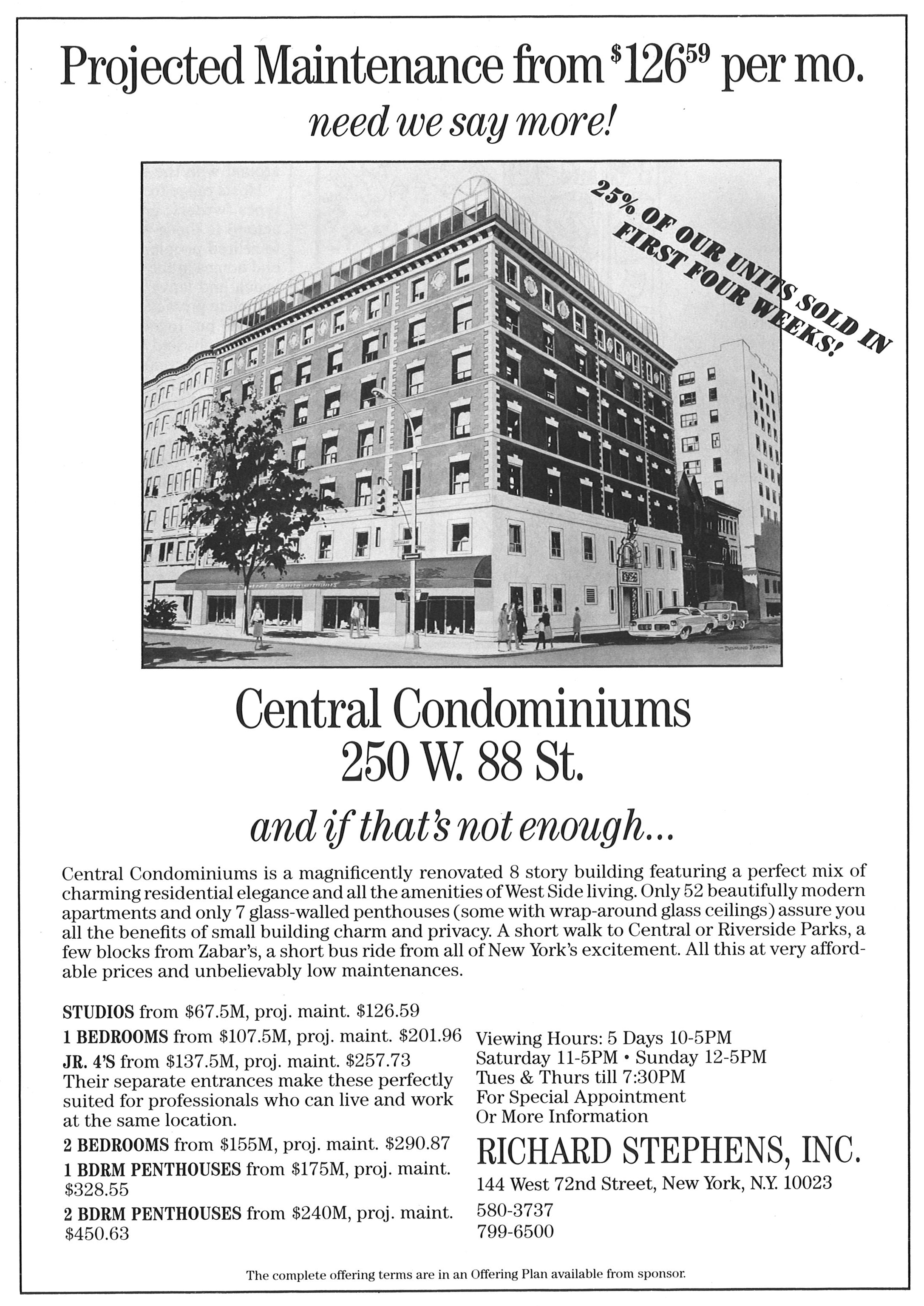

The plans, filed in January 1895, called for a “7-story brick, blue[stone] and limestone apartment house” to cost $300,000 to construct (nearly $10 million in 2022). Completed in 1896, the Metropolitan Apartment Hotel had retail space on the avenue. Its residential entrance within a double-height arch crowned with fluted keystones, sat demurely away from the busy Boulevard, at 250 West 88th Street.

The high-toned residents of the Metropolitan enjoyed the latest in amenities, like elevator service. Unfortunately, that resulted in a tragic accident on September 7, 1897. The engineer (or maintenance man), Frederick Reynolds had work to do on the elevator, so he sent it to the second floor and lowered a ladder into the shaft. While he was working, reported The Sun, “somebody got on the elevator car…and lowered it. Reynolds was crushed under it, and his breast bone and six ribs were broken.”

Lucy Field and her sister Susan were born nearly ten years apart—in 1851 and 1860 respectively. They came from an old English family in America, tracing their ancestors here to the 17th century. Despite the difference in their ages, the women were obviously very close. Lucy and her husband lived in the Metropolitan Apartments in 1901, as did Susan and her husband, Charles Lee.

MacDonald saw the disabled vehicle just in time to shut off his motor, but not soon enough to bring the car to a stop.

Before Henry Ford’s Model T appeared in 1908, automobiles could be afforded only by the upper classes. Among those privileged vehicle owners in 1905 was resident Ronald H. MacDonald. But machines and horses often made bad road partners. On Christmas Eve that year, MacDonald was driving along the Pelham Road. Further up the road, Joseph Trainor and his wife were having a problem. The running gear of their runabout—a buggy pulled by one horse—had snapped, frightening the horse. The New York Press reported, “Mr. Trainor was afraid to leave the reins out of his hands long enough to go to the animal’s head and quiet it, and Mrs. Trainor volunteered to do so.” Just as she reached the horse, MacDonald’s vehicle appeared out of the darkness.

MacDonald saw the disabled vehicle just in time to shut off his motor, but not soon enough to bring the car to a stop. The New York Press said, “It struck the runabout, throwing Mr. Trainor out and shoved the horse over against Mrs. Trainor, who was knocked down.” The horse broke free and galloped off. In the meantime, Trainor had landed on the pavement directly in front of MacDonald’s automobile. Luckily, MacDonald was able to veer onto the sidewalk to avoid running him over. The Trainors’ injuries were slight enough that they were treated at a nearby drugstore. Trainor refused to make a complaint against MacDonald, saying it was merely an accident and he had no lamps on his buggy.

The store at 2393 Broadway was home to a Huyler’s chocolate shop at the time. Founded in 1874, Huyler’s was by now the largest and most prominent chocolate maker in the United States, with more than 50 stores across the United States. The shop would remain here at least until 1915.

Among the most well-known Metropolitan residents was architect Francis H. Kimball, here by 1908. Born in Kennebunk, Maine on September 23, 1845, Kimball was married to the former Jennie G. Wetherell. He had designed some of Manhattan’s most impressive skyscrapers, like the Manhattan Life Building (the pioneer in steel construction in New York City), the Empire and Trinity Buildings on Lower Broadway, and the City Investing Building. Like the Field sisters, he came from an old American family, his first ancestor landing in New England around 1660.

On August 12, 1908, when most Americans were returning from Europe, the New York Herald reported that the Kimballs were boarding the Adriatic to head there. The article explained, “Mr. Kimball has built many of New York’s skyscrapers, and it is his custom to make a trip every year to Europe for the purpose of studying various forms of architecture in different countries.” This year the Kimballs’ extensive trip would take them to Holland, Russia, Denmark, Norway, and Sweden.

The residents of the Metropolitan Apartments, like all well-to-do New Yorkers, spent their summers abroad, at their country homes, or at fashionable resorts. The summer home of retired banker E. E. Leland and his wife was in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. Before leaving the Metropolitan in 1912, Mrs. Leland looked for a companion for her husband, who had lost his eyesight. She read an advertisement placed by “an educated Englishman” who was looking for such a position. Alfred Hicks was interviewed and hired, and he accompanied them to Stockbridge.

After the Lelands had gone to bed on August 1, Hicks vanished. The Sun wrote, “At the same time went eight or nine stickpins, some tie clasps, a diamond ring and a pair of cameo cuffs which had been worn by an ancestor who served with George Washington in the Revolution.” Mrs. Leland proved to be a perceptive detective. Expecting that Hicks would try the same ploy on a new victim, she closely read the newspapers for his advertisement. One week later, an almost identical ad appeared, giving the address of 93 West 116th Street. Detectives followed Mrs. Leland’s lead and arrested Hicks. One of the tie clasps was found in his possession. Mrs. Leland was not yet done with her detective work. The Sun reported, “Mrs. Leland said she had heard he was engaged to a girl named Lena and she wants to find out if she knows what the man did with the rest of the property.”

The Broadway shops continued to house a variety of tenants. In 1912 the Thomas Cook Travel Agency occupied 2389, followed by the Kops Millinery shop in 1919.

The affluence of the Metropolitan’s residents made it a tempting target for burglars. Between 1919 and 1921 five apartments had been burglarized. And there was about to be a sixth.

Fleischmann lamented that jewelry could be replaced, but the fight tickets could not.

Living in a fourth-floor apartment in 1921 was William N. Fleischmann. On June 1, his brother, Paul, and his sister-in-law, who had been visiting, were preparing to leave the next morning. The New York Herald wrote, “Mrs. Fleischmann withdrew $16,000 in jewelry from a safe deposit vault and packed it in her trunk.” The timing could not have been worse. Thieves broke into the apartment that night and made off with $20,000 worth of jewelry (more than $300,000 today). “But far, far worse than that,” said the New York Herald, “they took with them four choice tickets for the Dempsey-Carpentier fight.” In addition to his sister-in-law’s jewels, the thieves had made off with $4,000 worth of his own studs and rings. “Also, of course, the fight tickets, which Mr. Fleischmann described yesterday in minute detail to the police,” said the article. Fleischmann lamented that jewelry could be replaced, but the fight tickets could not.

A colorful resident was Lloyd B. Carleton, an actor and stage and motion picture director. Born Carleton B. Little, he took the stage name of Lloyd B. Carleton at the advice of famed impresario Charles Frohman. After a stellar career on the stage, he went into silent movies with the Biograph Company. Later he directed films for Universal Pictures before heading his own company, Lloyd Carleton Productions, Inc. Following his retirement and return to New York, he moved into the Metropolitan Apartments in the late 1920’s.

The changing neighborhood was reflected in a renovation to the building in 1935. Now called the Central Apartments and no longer upscale, its rooms rented for $8.50 a week. Among the transient tenants in the summer of 1937 was the 55-year-old Flora Aronson. On the afternoon of July 6, a maid came into her room to clean it. Aronson told her she was going to the roof for fresh air. Twenty minutes later a building employee, Sam Pullman, heard a loud thud and called a passing patrolman, William Crygan. They found Flora Aronson’s body in the courtyard. The Sun commented, “Mrs. Aronson had been ill for a long time and had been under a doctor’s care.”

Another renovation, completed in 1950, reconverted the building from rented rooms to apartments. The Central was converted to a condominium in the mid-1990’s. Above the two-story base, the façade is wonderfully intact after 126 years.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

Building Database

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the business currently at 250 West 88th Street:

Meet Salli Subryan!