‘Reliable Druggists’

by Tom Miller, for They Were Here, Landmark West’s Cultural Immigrant Initiative

Irish-born Edward Kilpatrick was brought to New York City by his parents at the age of 11. Starting out his career as a carpenter, by the 1880’s he had established himself as a building and developer, and eventually a respected architect.

In 1893, he purchased the entire blockfront on the east side of Columbus Avenue between 68th and 69th Streets. He designed and erected two back-to-back, mirror image “flat and store” buildings on the site.

Like its southern twin, 191-199 Columbus Avenue was designed in a blend of the Romanesque Revival and Renaissance Revival styles. Five stories tall, its Columbus Avenue side contained retail stores. The four upper stories were faced in warm orange brick and trimmed in brownstone. Residents entered around the corner at 76 West 69th Street.

The stores were leased to a variety of tenants. Sheet metal contractor Charles Werner’s office was in 191 Columbus Avenue. He advertised himself as a “first-class tin and sheet iron worker” for the installation of cornices, skylights, furnaces, ranges, and heaters. M. Dervieux ran his “French Steam” dry cleaners next door at 193 Columbus Avenue. An advertisement in October 1899 touted “dyeing, cleansing & refinishing, dry cleaning, high class and delicate work a specialty. Feathers cleaned and dyed.”

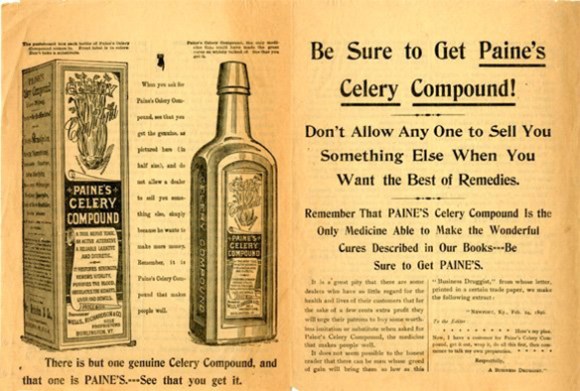

The real estate office of R. Westbrook Meyers occupied 195 Columbus Avenue, and John Denner’s pharmacy was in 197. A journalist from The World dropped into the drugstore in May 1896 to inquire about Paine’s Celery Compound. Denner seems to have been hesitant to give an endorsement, saying only, “I notice that the people who buy it once generally come back for more, and those who have said anything at all to me about it say it is an excellent nerve remedy…People won’t keep on buying a remedy unless it does them good.”

Like its southern twin, 191-199 Columbus Avenue was designed in a blend of the Romanesque Revival and Renaissance Revival styles. Five stories tall, its Columbus Avenue side contained retail stores.

In the meantime, the residents in the upstairs apartments were financially comfortable. Each would have had at least one servant, certainly a housemaid.

Mrs. Thomas Vonderluke could also afford the popular and expensive fad of bicycling in the 1890’s. The price of a ladies’ bicycle ranged between $2,500 and $3,000 in today’s money. But, it was not her mode of transportation that drew the attention of the press in 1894, it was her choice of apparel.

The Chicago newspaper The Inter Ocean noted on June 3, “The prejudice against bloomers which existed among women cyclists when that mannish costume was first introduced is rapidly disappearing.” (The term did not refer to the undergarments of the Civil War period, but a combination skirt-pant affair, similar to culottes in the 20th century.) The article said that upwards of “a hundred women in New York…wear trousers while astride their wheels.” It admitted, however, that “not all the hundred women who ride in trousers do so openly. Many of them confine their trips on the wheel to the night.” Listed among those progressive, bloomer-wearing New Yorkers was Mrs. Thomas Vonderluke.

Artist Gertude P. Harrington lived here in 1897. Her apartment doubled as her studio for tutoring drawing students.

Albert F. Ram and his wife welcomed a baby son, Lawrence, on June 15, 1899. When the infant developed colic Dr. J. E. Newcomb prescribed “a soothing medicine,” as reported by The New York Times. At around 10:00 on the morning of June 22 the baby was fussing, and Albert instructed his nurse, Elizabeth Borinjiaux to give him a dose of the medicine.

Possibly because English was not the French woman’s first language, she made a horrifying mistake. The Evening Post reported, “In the presence of Mr. Ram she took a bottle from a shelf, on which the medicine was kept.” She gave the nine-day-old baby carbolic acid rather than his medicine. The child “died from exhaustion at one o’clock this morning,” reported the newspaper the following day.

The New York Times added, “Both the mother and the nurse were overcome by the death of the child.”

By 1911, John Denner’s pharmacy had become the A. J. Bauer & Co. drugstore. It would remain in the space at least through 1922. The store at the other end of the row played a part in women’s rights history in 1918 when it was used as a registration site for newly eligible female voters.

On May 25 one young woman strode in “wearing, among other things, a green tam o’shanter and a purportful air,” said the New-York Tribune. She carried a stack of pamphlets that advised women about the process. She told a reporter, “I’m equipped to avoid the male snicker. We must be educated to vote intelligently.”

In February 1922 a detective was in a drugstore when he overhead a telephone conversation during which a man received an order “for an unusually large amount of narcotics,” according to The New York Times. He wrote down the address—76 West 69th Street.

Undercover detectives staked out the entrance from across the street. When they recognized a known drug dealer enter the building at around 11:00 on February 24, they followed. Back-up arrived and a raid was made “on a luxuriously furnished apartment on the third floor,” reported The New York Times. The occupants, “two fashionably dressed, bejeweled young women,” were arrested on charges of possessing narcotics. One of them had rushed to the window and thrown several vials to the street. But it was to no avail. Detectives confiscated “eight vials of heroin and morphine and a small tin box containing a white powder.”

The women identified themselves as Hazel Housee and Evelyn Hill, both 26-years-old. The New York Times said that when they appeared at the police station, “Hazel Housee wore an ermine cape over an expensive evening gown, while the second prisoner was clothed in a mink coat and a hat from which birds of paradise feathers streamed.” The Special Deputy Police Commissioner told reporters that the names were fictitious and that Evelyn Hill “really was a prominent motion picture actress.”

She told a reporter, “I’m equipped to avoid the male snicker. We must be educated to vote intelligently.”

Two other female residents found themselves behind bars three years later. On December 22, 1925 Mrs. Lillian Spencer and Mrs. Grace Letcher, 39- and 38-years-old respectively, made the foolish mistake of returning to the scene of a previous crime. Six days earlier, they had walked out of George Tabet’s Madison Avenue shop with $125 worth of Normandie lace doilies for which they neglected to pay.

They apparently did not suspect that Tabet knew it was they who were the shoplifters or guess that he would remember their faces. They were wrong on both accounts. When they left his shop the second time, they were in handcuffs.

The long tradition of a pharmacy occupying the store 197 Columbus Avenue continued in the 1940’s with Reliable Druggists. That came to an end by 1994 when Genghiz Khan’s Bicycle, a Turkish restaurant, opened in the space. It signaled a trend along the row.

In 1981, Empire Szechuan opened in 193 Columbus Avenue and remains there today. And, in 1988 the Oyshe Restaurant occupied 199 Columbus Avenue. In 2012 the three northern stores were combined for the London-based apparel retailer Reiss. Today 191 Columbus houses an art and frame shop.

The upper floors of Edward Kilpatrick’s handsome flat building are remarkably the same after more than 125 years.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

191-199 Columbus Avenue

Keep

Exploring

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 191-199 Columbus Avenue: