The Greylock Apartments

Communists and Carrier Pigeons

by Tom Miller, for They Were Here, Landmark West’s Cultural Immigrant Initiative

The residents of the new Upper West Side were among the first to embrace apartment living. Among the developers who joined in the flurry of construction was John Conley who bought the two plots at the northeast corner of Ninth Avenue (later renamed Columbus Avenue) and 74th Street in February 1890. He announced his intentions of erecting a “seven-story apartment house” with the latest in amenities like an elevator and steam heat.

Architect Gilbert A. Schellenger designed the building, which was named The Greylock. He married two popular styles—Romanesque Revival and Queen Anne—to create a formidable structure. The residential entrance was centered on the 74th Street side within a base of rough-cut brownstone. It was pure Romanesque. The chunky brownstone continued upward for two stories. Otherwise, the façade was clad in brick and trimmed in stone and terra cotta, as well as bowed cast metal bays placed asymmetrically along the 74th Street elevation (typical of the Queen Anne preference for designs being off-balance). The top floor detonated in a mountainscape of dormers, gables and blunt towers.

The ground floor held shops which produced additional income for Conley. The corner store became the flower shop of Greek immigrant Evangelos R. Lucatos. By 1905 it had been taken over by Lambros Mulinos who lived downtown at 147 West 20th Street and ran a second flower shop on Sixth Avenue.

By 1916 the business had been taken over by Mulinos’s son and renamed George Mulinos & Sons. The Mulinos family lived upstairs in the building. When World War I broke out George Jr. left to fight and would never return. He died in battle in 1918. The following year directories listed his mother, Helen Mulinos, as the sole owner of the flower shop.

The diversity of the Greylock residents was reflected not only in the various countries from which they came; but in their religious beliefs.

In the meantime, the residents of the Greylock were mostly professional. Dr. George Jarman lived here in 1894, around the same time that Dr. Josephine Walter moved in. In 1898 she was appointed by the Board of Education to examine prospective teachers regarding their health. It may have been the fact that she was female that helped her land the position at a time when most teachers were women. She would remain in the Greylock at least through 1912.

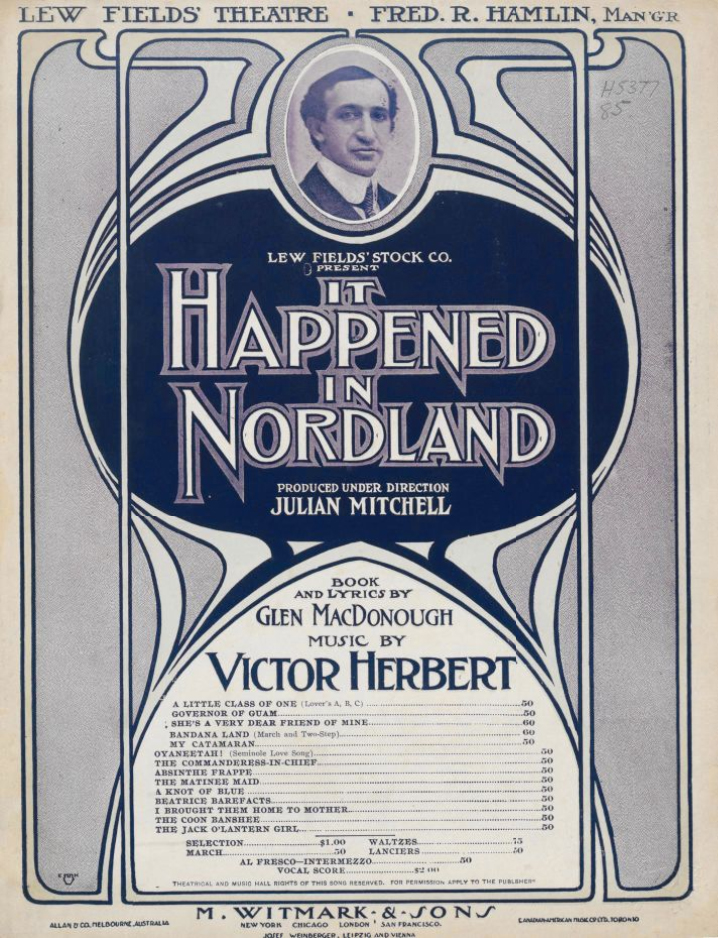

At the turn of the century people involved in the theater were not always welcome in some sections of the city. That was not the case on the Upper West Side and in 1904 actress Billie Norton lived in the Greylock. She was playing the role of Secretary to the American Ambassador in the Lew Fields production of It Happened in Nordland in December that year when she disappointed audiences by falling ill. The Morning Telegraph explained “She is ill at her home, 61 West Seventy-fourth street, and has symptoms of pneumonia.”

The William Vincent Cutajar family were long-term residents of the Greylock. In 1910 Huyler’s candy company offered cash prizes for fresh advertising ideas. Charles Julian Cutajar won the $30 second prize—nearly $825 today. His sister, Beatrice Lanier Cutajar, was introduced to society by their mother at an afternoon reception in the apartment in December 1912.

The diversity of the Greylock residents was reflected not only in the various countries from which they came; but in their religious beliefs. An example was the Jewish David family, here by 1910. Aaron H. David was a tile layer. As a hobby he kept carrier pigeons in coops on the roof. That spring, however, his attentions were more focused on a young lady, Hattie Moses, the daughter of manufacturer Max Moses. After he had called on her for a few months Hattie’s parents worried that things were getting too serious. The Sun noted that they “liked the young man well enough, but not enough to admit him to the family.” And so, toward the middle of July they told him to stop seeing their daughter.

The sweethearts had already secretly agreed to marry. Now unable to see one another, they communicated through Aaron’s carrier pigeons as they plotted their elopement. They arranged to meet at 10:00 on the morning of Friday July 15 and rushed to City Hall where they obtained a marriage license. They then went to the home of Aaron’s aunt on East 158th Street, called in a rabbi, and were married. Now that the deed was done, Hattie’s parents were notified by phone.

Her mother played it cool. “Oh, well, I’m not going to be excited. You’ll be home this afternoon, though, won’t you?” Elated, Aaron promised they would stop by at 4:00. And when they did the police were waiting for them. Mrs. Moses told them “I want you to arrest this young man for abducting my daughter.”

Hattie stepped in, though, and informed the officers she was 18-years old and could make her own decisions. Unable to proceed with the arrest, the police left. But Mrs. Moses was not done. She locked Hattie in a room and Aaron was “driven from the house.” Now it was he who went to the police and obtained a summons. But when he arrived at the house on Saturday, July 23, the house was empty, and the Moses family was gone.

When 18-year old John A. Meyer was fined $15 for speeding on August 27 that year, he “whistled in surprise,” as reported by the Yonkers newspaper The Herald Stateman. Judge Martin J. Fay responded by raising the fine to $20.

The tenant list continued to include several medical professionals. Dentists J. Grant Pease and George A. Fournier were in the building in the pre-World War I years. Fournier, described by The New York Herald as “a wealthy dentist” owned a motorcar in 1914. He turned from Delancey Street onto the Bowery on the night of June 15 right into the path of Fire Chief “Smoky” Joe Martin’s official vehicle. Martin was on the way to a small fire with Fireman Ernest Roeber driving. Seeing the red car coming, Fournier veered to avoid a crash. The chief’s car hit the curb and then struck a pillar of the elevated train. Martin insisted that Fournier had sideswiped his automobile and had him arrested for reckless driving.

The family of William G. Collins and his wife, the former Bertha W. Armstrong, had lived in the Greylock for several years at the time. Son William Major was a physician, and Kenneth Benedict was involved in his father’s company, the Collins & Alkman Company which had a second office in Philadelphia.

Kenneth had surprised everyone when he married concert vocalist Mme. Estelle Burns-Roure in Tyler Texas in March 1912. None of their friends knew that they were romantically involved; and what made the wedding even more unexpected was that the very reason that his bride had gone to Texas was that her father had died just days before. The Collins family remained in their apartment for years to come.

And advertisement in 1922 offered a first-floor apartment of eight rooms and two baths for $3,000 per year—or about $3,750 a month in today’s dollars. It noted that the space was “suitable for doctor or dentist.”

Teen-aged boys in 1936 had forgotten traditional manners, at least one judge thought so. When 18-year old John A. Meyer was fined $15 for speeding on August 27 that year, he “whistled in surprise,” as reported by the Yonkers newspaper The Herald Stateman. Judge Martin J. Fay responded by raising the fine to $20. When Meyer mumbled something loud enough for the judge to hear he was given a lesson in “what ‘being fresh’ can do.” The judge handed him a two-day sentence in City Jail. While he sat on the prisoner’s bench, the Meyer suddenly regained his social graces. He asked if he could talk to the judge, and he then apologized. He was given a one-day reduction in sentence.

In 1947 a special Congressional Subcommittee on the Investigation of Communism in New York City Distributive Trades was formed. Its findings reported that “The Herald Square Club of the Communist Party has held secret meetings at…61 West Seventy-fourth Street, apartment 5A.”

The space that had been home to florist’s shops in the 1890’s and early 1900’s was home to Cheese’n-Things in 1975; a sort of food boutique. Café Europea had moved into one of the spaces by 1979, and in 1987 another was leased for an Alain Manoukian store, described by New York Magazine as “an upbeat Gallic version of Ann Taylor.” That same year Le Sweaterie, a European retailer, opened in 303 Columbus Avenue.

Today the corner store is an HSBC bank branch. In the 74th Street store is Patsy’s Pizza, a neighborhood fixture since the late 1990’s.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

301 Columbus Avenue,

The Greylock Apartments

Keep

Exploring

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 301 Columbus Avenue: